In 2018, flooding over Father’s Day weekend carved a hole through a major highway in far northwestern Wisconsin, disrupting travel for months and sending three times the amount of sediment that flows each year into one Lake Superior bay. Now, a project aims to slow the flow of runoff as the region faces more frequent, intense storms due to climate change.

Around 45,000 tons of sediment surged downstream into the Chequamegon Bay during the once-in-a-lifetime storm that marked the region’s third 500- to 1,000-year rainfall event in just seven years. While the section of U.S. Highway 2 has long since been repaired, the flood created a 630-feet-long and 55-feet-high scar along the north fork of Fish Creek, west of Ashland.

“This is ground zero for sediment and phosphorus contributions to Chequamegon Bay,” said Matt Hudson, associate director of the Mary Griggs Burke Center for Freshwater Innovation at Northland College.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

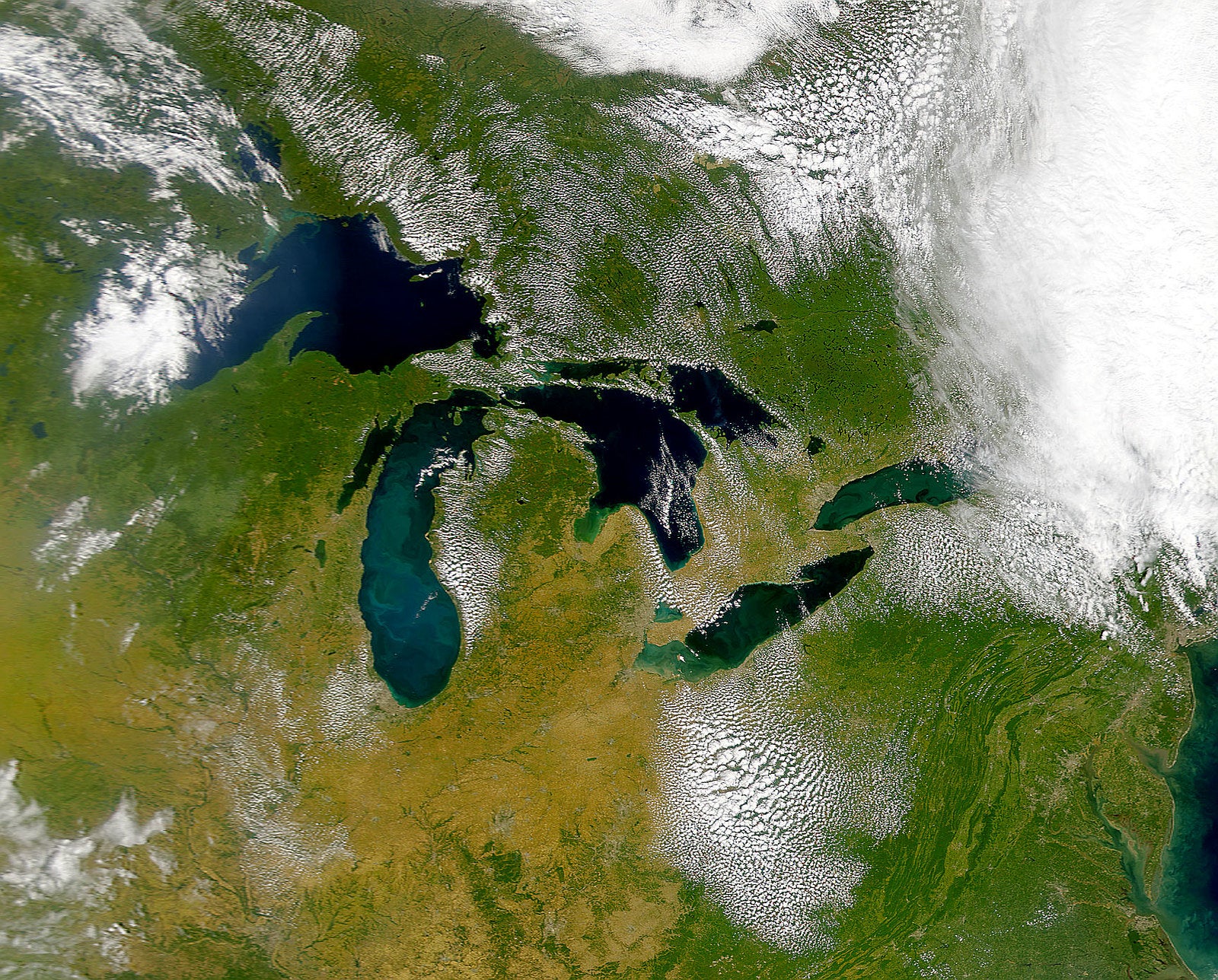

Now, a mix of local, state and federal partners are wrapping up a $320,000 restoration project funded through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative as part of a broader years-long effort to slow the flow of runoff into the Chequamegon Bay of Lake Superior. The project aims to prevent eroding bluffs from sending around 5,600 tons of sediment each year downstream into the bay and ultimately Lake Superior.

“It will lessen sediment that covers trout spawning gravel in Fish Creek and reduce sediment that flows into Lake Superior, where the city of Ashland gets its drinking water,” said Ted Koehler, a fish biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The influx of sediment poses threats to fish and wildlife habitats in Fish Creek — a Class I trout stream — and costly water treatment for Ashland residents. Sediment pollution is estimated to cause around $16 billion in environmental damage each year nationwide as particles cloud the water, preventing fish from seeing food and absorbing warmth from the sun.

While bluffs along the creek are naturally susceptible to erosion, Hudson said human activity has exacerbated the problem and climate change is only making it worse.

Nutrients that run off into the lake along with sediment following large storms are seen as factors that set the stage for blue-green algae blooms to form. Despite the lack of rain, Lake Superior saw half a dozen minor blooms this year as it’s become one of the fastest warming lakes in the world.

“This project will build resilience to our natural systems as a buffer against our changing climate,” said Hudson.

Engineering firms Inter-Fluve and Fish Creek Restoration, LLC, have been working on the project’s design and installing layers of logs into the stream bed, which are cabled together near the base of eroding bluffs along Fish Creek. The logs are designed to keep the creek from migrating toward its banks while also serving as fish habitat. The creek is also being redirected to follow the path it flowed prior to the 2018 flood.

Hudson said they expect the project to hold up in the face of intense storms like those seen in 2018. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation installed a bridge on the section of road that failed during the flood as a culvert was unable to handle the wall of rushing water. Hudson noted the improvements should prevent that kind of dam release of water downstream.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Deputy Secretary Todd Ambs said about 40 percent of waterways on Wisconsin’s impaired waters list were added due to excess sedimentation. Although, the segment of Fish Creek that’s undergoing restoration has not yet been listed.

“Sediment from this creek is relatively clean by comparison to sedimentation that you’ll have downstate that could have very high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural practices. And, certainly, we have sites in the state that have significant contaminated sediment,” said Ambs. “So, it is a big issue. It’s a big challenge. It’s a big focus of the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.”

The project is one of more than 6,000 that have been funded with nearly $4 billion awarded since 2010 through the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Wisconsin has received around $405 million for more than 500 projects that seek to clean up areas along the Great Lakes and reduce runoff from sites like Fish Creek. One study from the University of Michigan found every dollar invested through the Great Lakes cleanup program provides around $3 in economic benefits across the region.

Climate change is placing additional stress on the Great Lakes region and its infrastructure, costing Wisconsin coastal communities around $245 million over the next five years.

Ambs highlighted that Gov. Tony Evers’ administration has increased focus on climate-driven challenges. Evers set a goal for the state to use 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2050 and created a task force to address climate change that issued a report with more than 50 recommendations.

That’s in stark contrast to former Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s administration, under which the DNR scrubbed climate change language from its website.

As the state witnesses more intense storms, Ambs said people are recognizing the connection between climate change and its effects statewide.

“When you look at what happened three times in seven years in this part of the state, you simply don’t find that historically, and it draws people’s attention to the need to do some more work to deal with this new reality,” said Ambs.

In the last two decades, there were 27 billion-dollar disasters that affected Wisconsin, representing $100 billion in impacts, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Ambs said the $1 trillion infrastructure bill in Congress could help address infrastructure that’s vulnerable to climate change. Democrats are at odds over federal spending packages that aim to address infrastructure and social programs as part of President Joe Biden’s economic agenda, which they aim to pass without Republican support.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story omitted an engineering firm working on the project. The story was updated at 11:36 a.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 29, 2021.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.