At the bottom of a steep country road outside of Cashton, Tucker Gretebeck’s farm opens up into a narrow valley, where tall grass hides fields of pumpkin vines and a small, unnamed creek.

“It’s got a lot of natural energy, just by the way the sun comes up and over the side of the valley,” he said. “At this time of the year, when you get the fall colors, it’s something that can’t be reproduced.”

Greteback milks around 50 grass-fed cows for nearby Organic Valley. Much of his farm sits on top of the ridge above, but the tucked-away valley is where he pastures cows in the hottest part of summer and runs a pick-your-own pumpkin patch in the fall.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

On the night of August 27, 2018, up to 12 inches of rain fell over southwestern Wisconsin in roughly six hours. Rushing down the steep slopes that characterize the Driftless Area, the water gathered behind a grass-covered flood control dam that cuts Gretebeck’s valley in half. Instead of slowing the flood down, it burst through the bluff of sandstone connected to the dam, sending a wave of water downhill to the nearby village of Coon Valley.

It was one of five dams out of 23 in the area that failed during the 2018 flood. The storm caused almost $3 million dollars in damage to homes and businesses in Coon Valley. Across Vernon County, the flood led to an estimated $14 million in damage to public infrastructure.

For Gretebeck and many residents in the area, everything changed after the disaster. Now, more than five years later, the dam on his farm still ends in an abrupt drop, with chunks of sandstone littering the valley.

“We’ve lived with these dams our entire lives, and when we had big rains, they held it back,” he said. “Once in a while, one would overtop or things would happen. But when you’re directly affected, it changes the way you look at the landscape.”

The 2018 flood is one of several historic floods that have hammered southwestern Wisconsin in the last two decades. Scientists expect the trend will continue as climate change causes more severe weather patterns.

Now, some leaders in the Driftless Area say the best way forward is not to rebuild bigger, stronger dams. It’s to remove dams like the one on Gretebeck’s farm altogether, and instead focus on putting more precipitation into the ground where it falls.

Dams will cost more to replace than the benefits they provide

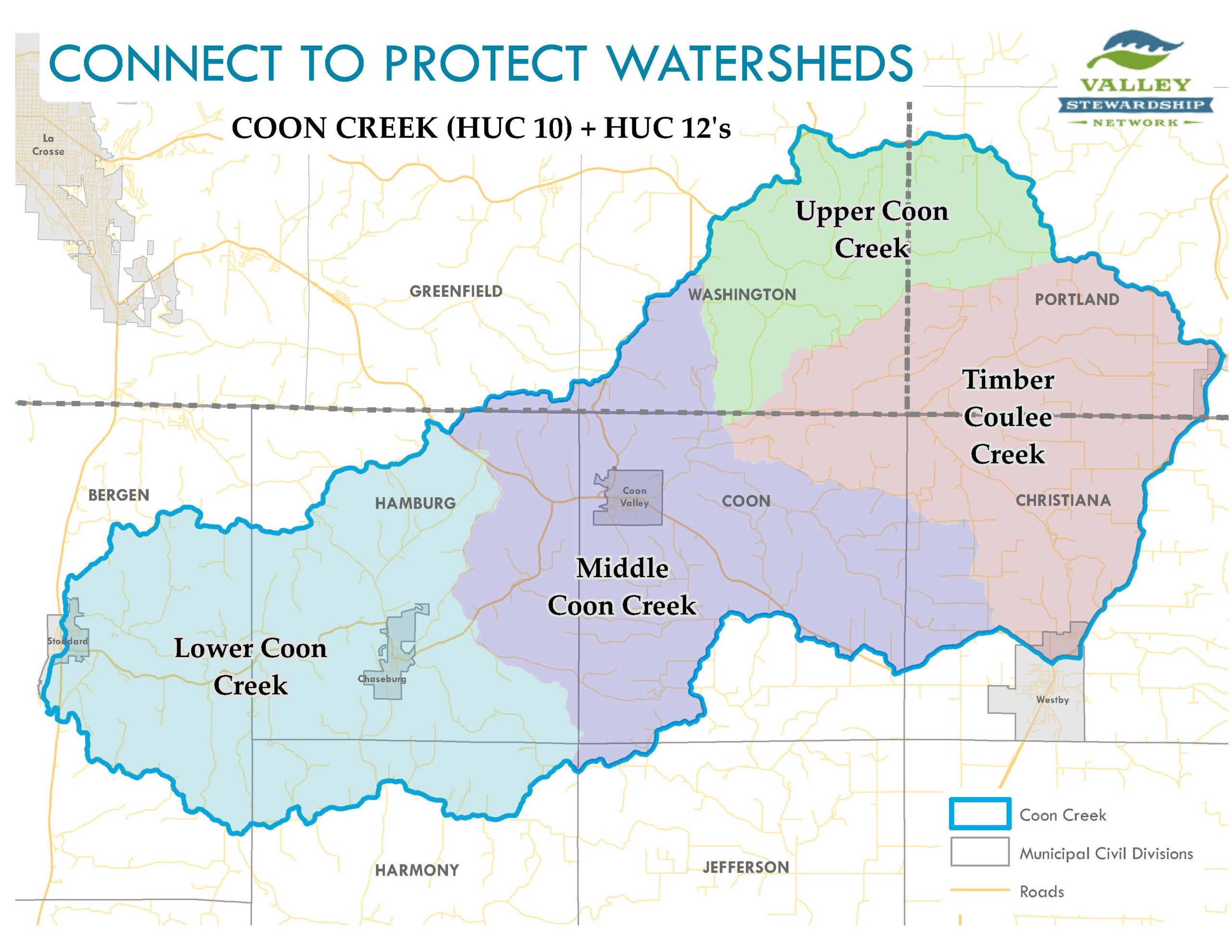

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, or NRCS, built the flood-control dams during the early 1960s, targeting areas like the Coon Creek watershed that had experienced repeated flood damage.

The grass-covered structures stand between 25 and 40 feet tall and were designed to slowly release floodwaters through a concrete spillway.

But the perception of security provided by the network of dams may be greater than the actual flood control benefits they provide, according to Steve Becker, NRCS’s state conservation engineer for Wisconsin. He said they only control 27 percent of the Coon Creek watershed.

“You don’t have to move too far downstream from the dam to where a lot of other uncontrolled water intersects Coon Valley and the benefits are diminished fairly rapidly as you move down the valley,” Becker said.

Becker and his team calculated the environmental, economic and social effects of the dams since their construction, using actual precipitation data from the last 60 years.

He said the dams have brought about 90 cents in flood control benefits for every dollar spent on construction and maintenance, a ratio which he said represents a good use of taxpayer dollars over the life of the structure.

But moving forward, the estimated cost-benefit ratio for rebuilding the structures is only 10 cents in benefits to every dollar spent. Becker said it’s mainly due to the high cost of construction needed to bring the dams up to current safety standards.

Because the cost of rebuilding far outweighs the potential benefits, NRCS is recommending that almost all of the dams in the two watersheds be decommissioned.

The only exception is Jersey Valley dam, which forms a recreational lake in Vernon County and had previous repairs done in 2010. Becker said the recreational benefits provided by this dam make the cost of replacing it worth the investment needed from both federal and county governments.

Since the idea of decommissioning was first raised, Becker said not everyone has agreed with the recommendation, especially those who live near a dam that wasn’t breached in the 2018 flood. He said some residents have advocated for leaving the structures in place until they need repairs, a risk that Becker said isn’t smart. Another dam collapse like those in 2018 would do more serious damage to properties and could even result in deaths if it catches people off guard.

“No one wants to see that type of a sudden breach,” he said.

Coon Valley watershed was home to nation’s first federal erosion-control project

This month, the NRCS will release the Coon Creek Watershed Project Plan for public comment. Becker said it will then be up to officials in the three affected counties — La Crosse, Monroe and Vernon — to decide whether to move forward with the plan to decommission the dams.

But one grassroots group isn’t waiting for local officials to make a decision.

“We know that there are structural issues (with the dams), and so what we need to do is learn to live without them,” said Nancy Wedwick, a longtime resident of Coon Valley and the president of the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council.

Wedwick said the idea to form a watershed council first came after the 2018 flood, when a group of local business owners were frustrated by the limitations of disaster recovery assistance from FEMA and other programs.

“What brought everybody together was the flooding and what could we do to help ourselves,” Wedwick said. “We started to learn a lot and we’ve been busy ever since.”

After a delay caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council was officially formed in 2021. It’s one of 43 watershed councils in the state that receives funding and support from the state Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection.

Wedwick said the group’s primary goals are to educate residents about the need to rethink land practices to prevent flooding and encourage people to take action on their own land. The group hosts field days for residents to demonstrate what’s worked on their property and has brought in experts from the Universities of Wisconsin system and conservation organizations.

Wedwick said her biggest motivation is knowing the community has done this work before.

In the 1930s, the Coon Creek watershed was home to the first federal erosion-control demonstration project in the nation. Conversion of prairie and forest land to farm fields by European settlers had left the sandy soils of the Driftless Area vulnerable to severe erosion and flooding. The Soil Erosion Service, an agency that would eventually become the NRCS, and the Civilian Conservation Corps worked with farmers around Coon Creek to develop practices like contour strips, where rows of perennial plants like alfalfa are interspersed through corn fields to slow water moving down a slope.

This innovative method, along with practices like terracing the land and planting forests, led to a dramatic decline in erosion and sparked soil conservation projects across the country following the Dust Bowl era.

Eric Booth, hydroecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said he remembers learning about the historic project in college classes.

“It’s the story of how we can change land use and land management for the better, to stem erosion and improve flooding outcomes,” he said. “Certainly in Wisconsin, it’s even more of a story that is told. But nationwide, people in soil conservation and water science know about the Coon Creek watershed.”

Booth said it’s clear from historical data that the practices adopted in the ’30s halted the erosion and flooding problems in the Driftless, even though it took decades to see the benefits. The delay is part of what led to the installation of the flood control dams in the 1960s, when floods were still happening occasionally and communities wanted more protection.

But unlike the flooding challenges faced in the early 20th century, Booth said the floods of 2007, 2008 and 2018 represent more intense rainfall events than the region had seen in recorded history. Scientists believe today’s flooding and erosion problems are driven primarily by a warming climate and the more intense hydrologic cycle it is likely to bring.

Booth said land use is still an important factor in how these more intense storms are playing out. As the number of dairy farms in the state has declined sharply over the last decade, the farmland of the Driftless Area has changed from cow pastures and fields of forage to rows of corn and soybeans without the erosion-protecting contour strips.

“When dairy farms went away, those contour strips started going away, too,” he said. “There’s still a lot of them out there, but they did start declining as we saw more and more dairy farms being lost.”

Community group says region can build resilience

This summer, Wedwick and her husband planted 100 trees on their property, which sits on the ridge directly above Coon Valley. She said it wasn’t until forming the watershed council that she realized the effect their land practices on the ridge had on their neighbors below.

“I was slow to connect the dots,” she said. “I think there are probably a lot of people still out there who do not realize what those effects can be and what you can do on your own land to hold the water back.”

Just like in the 1930s, she said it will take a coordinated effort to get farmers and landowners on both the high ground and in the valleys to make changes that will slow down the water.

Gretebeck, who is vice president of the watershed council, said on top of this education, the group is working to bring together all of the residents in the watershed — something he said can also be traced back to the 2018 flood.

“We met neighbors that we didn’t know were there,” he said. “Everybody joined together. In Coon Valley, people showed up with their boots and a shovel and said, ‘Can we help you muck out your basement?’ It was just an event so big that it bonded all of us.”

In September, the council hosted a 90th anniversary celebration for the original Coon Creek Watershed Project. The event included tours of infrastructure built by the Civilian Conservation Corps that is still a part of the landscape and ended with dinner at Gretebeck’s farm.

Wedwick said it was an opportunity to celebrate the history of their area, while also acknowledging the new set of challenges the region faces.

“Here we are, again, now 90 years later,” Wedwick said. “We’ve lost our way in some cases, and that of course is compounded by the changing climate and all of the weather that we are now seeing. But the important thing to remember is that we did this before. We know how to do this.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.