Was Judge Hannah Dugan an obstructionist who knowingly and “corruptly” tried to stop federal law enforcement officers from arresting a perpetrator of domestic violence?

Or was she just a judge trying to do her job and manage her courtroom as she saw fit?

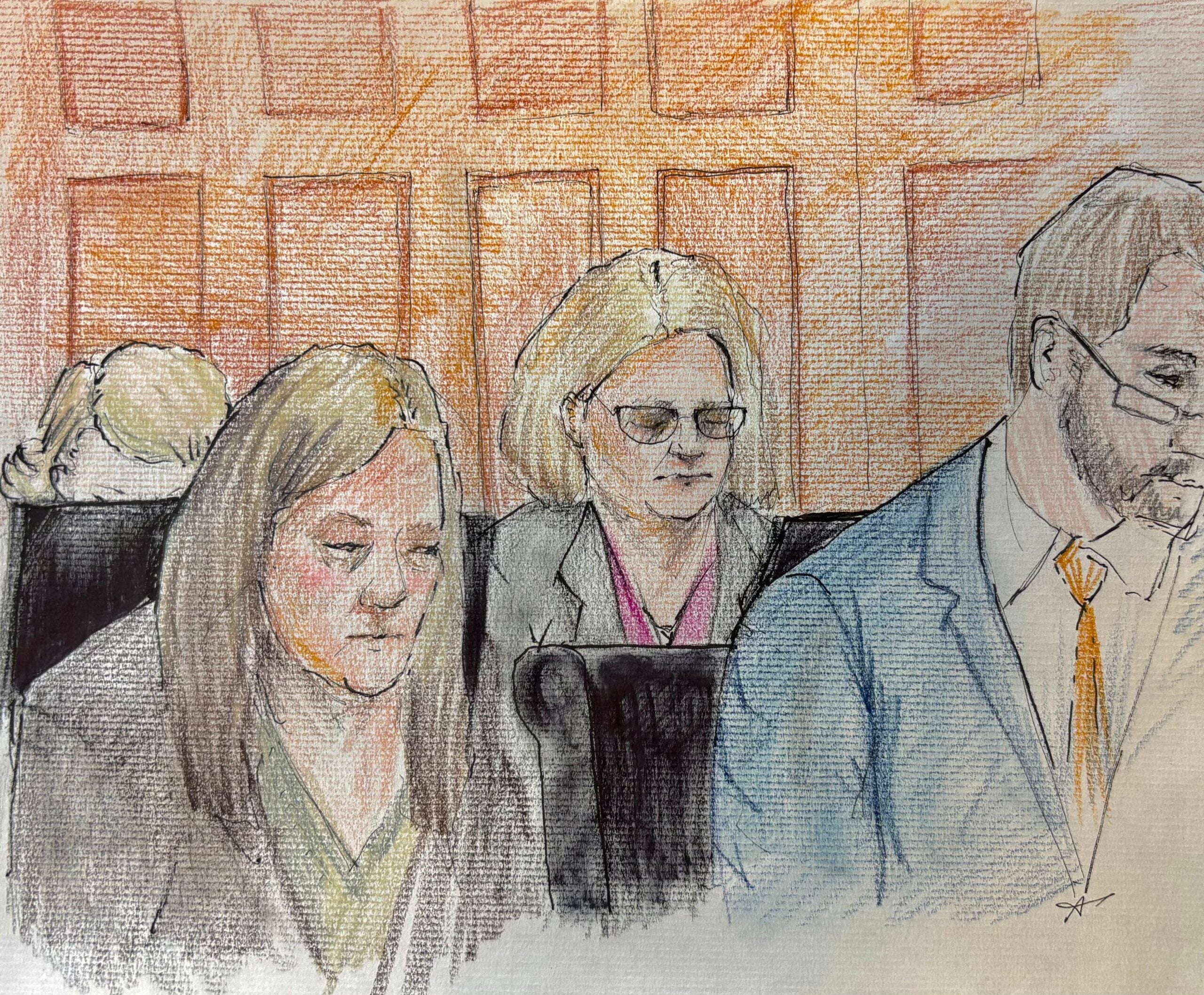

Attorneys for both sides made their opening arguments Monday on the first day of the trial against the Milwaukee County judge.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Federal prosecutors and Dugan’s defense team agree on several basic facts about the incident on April 18. Federal agents showed up at the Milwaukee County Courthouse that day with an administrative warrant to arrest Eduardo Flores-Ruiz for being in the country illegally.

After most of those agents left to speak with the county’s chief judge, Dugan led Flores-Ruiz out a side door of her courtroom and told his attorney his hearing would be rescheduled to take place over Zoom.

Prosecutors: Dugan ‘knew what she did was wrong’

But during oral arguments, attorneys for each side presented dueling characterizations of Dugan’s mindset and whether or not what she did was illegal.

“The defendant knew what she did was wrong,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Keith Alexander told the jury. “In fact, she said, ‘I’ll get the heat.’”

Dugan faces two federal charges — obstructing or impeding a proceeding and concealing an individual to prevent his discovery and arrest.

During opening arguments, Alexander played audio from Dugan’s courtroom and showed video and still shots from courthouse security cameras. He alluded to emails that Dugan sent before the events of April 18, in which Dugan expressed “strongly held” concerns about arrests by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in or near the Milwaukee County Courthouse.

Alexander said Dugan is not on trial for her views.

Rather, he contended, “She is on trial today because those strongly held views motivated her to make a decision to cross the line.”

Defense: Dugan’s actions were a routine part of a judge’s job

But defense attorney Steve Biskupic told jurors that’s not the case.

“This week, she’s on trial because the federal government wanted her to act a certain way with respect to ICE, and she didn’t act that way,” said Biskupic, who formerly served as U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Wisconsin.

Flores-Ruiz had been scheduled to appear in Dugan’s courtroom on April 18 on misdemeanor domestic battery charges. After Flores-Ruiz left the courthouse, agents chased him on foot and arrested him outside.

The Mexican national was deported in November after pleading to no-contest to a battery charge in Milwaukee County Circuit Court.

Biskupic said Dugan can’t be found guilty “by association” for the fact that Flores-Ruiz decided to run from agents.

“All she did was send (him) out the hallway,” Biskupic said.

The side door through which Dugan ushered Flores-Ruiz is normally used by jurors and court staff. Biskupic said that door is only “11 feet 10 inches” from the main doors to the courtroom.

Biskupic argued Dugan can’t be found guilty of the charges against her because she had no “corrupt” intent to prevent Flores-Ruiz’s discovery by agents, and she didn’t actually obstruct his arrest.

Biskupic said it’s “routine” for judges to reschedule hearings on the fly and decide that certain proceedings should take place remotely.

The case against Dugan is being overseen by U.S. District Court Judge Lynn Adelman, who was first appointed to the federal bench by then-President Bill Clinton.

It’s received national attention as President Donald Trump’s administration has overseen a massive immigration crackdown.

Last week, the court selected 12 jurors and two alternates to hear the case. Adelman announced Monday morning that one of those people was sick, which caused the case to proceed with one alternate. Opening arguments wrapped up by mid-morning.

Prosecutors call FBI agent as first witness

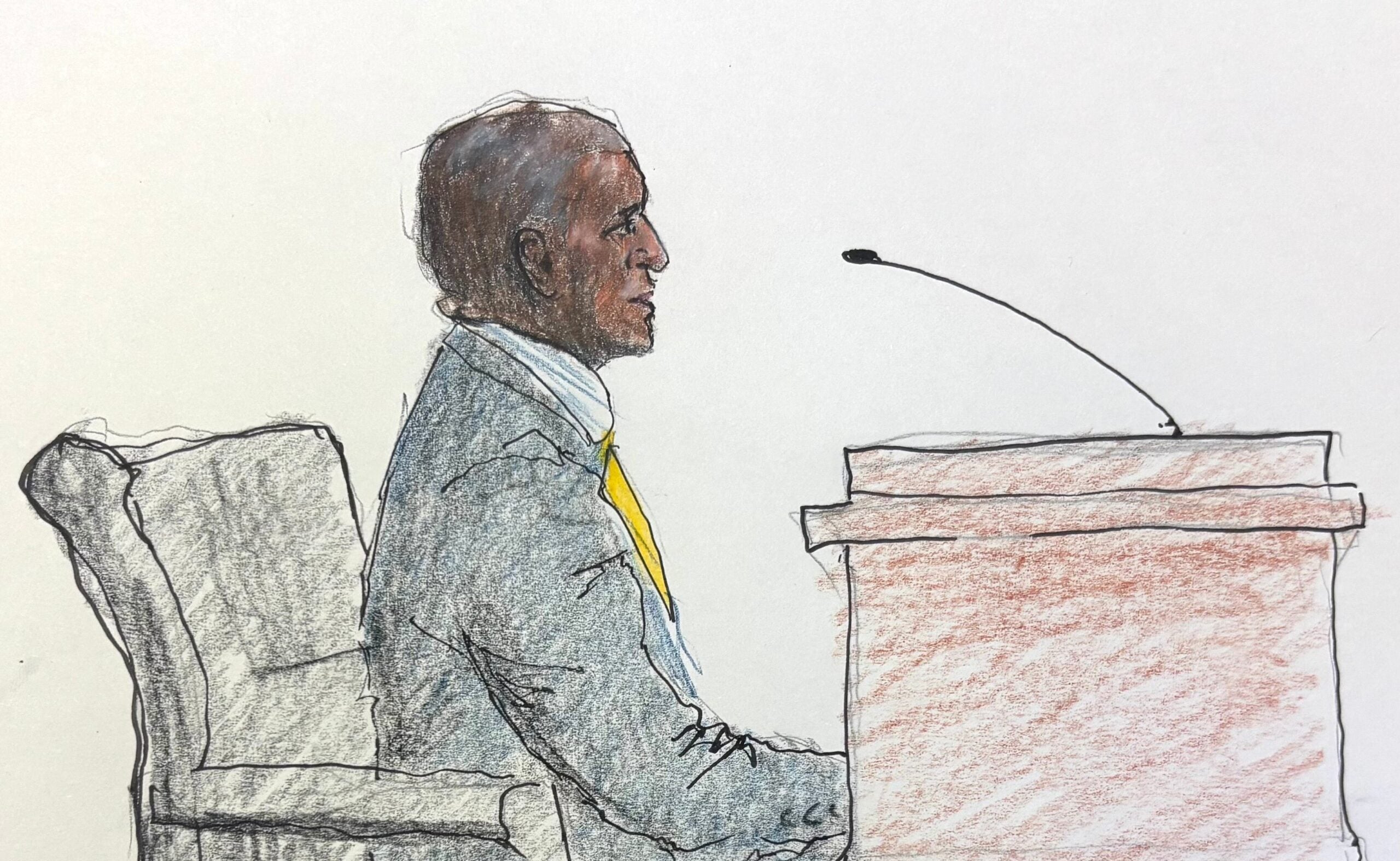

For the trial’s first witness, prosecutors called upon Erin Lucker, a special Federal Bureau of Investigation agent who led the case against Dugan.

During Lucker’s testimony, prosecutors walked the jury through the government’s timeline of events and paused at multiple points to play security video. Prosecutors also played audio that had been recorded from courtroom microphones that are typically used by court reporters.

That includes audio where Dugan says, “I’ll do it. I’ll take the heat.” Prosecutors indicated Dugan had been speaking to her court reporter.

Prosecutors allege that Dugan was directing Flores-Ruiz and his attorney to go down a set of courthouse stairs. They pointed to that as evidence that Dugan had told Flores-Ruiz to leave through a path that was intended to help him avoid detection.

During cross-examination, defense attorney Jason Luczak asked Lucker about a group chat that agents involved with the Flores-Ruiz were part of on the encrypted messaging app Signal.

Luczak said agents had titled the chat “frozen water” — seemingly a reference to the word ICE.

He asked Lucker whether that title was supposed to be funny.

Lucker said she wasn’t part of that chat, so she couldn’t say.

Prosecutors argued that line of questioning was irrelevant and tried to shut it down. Adelman, however, allowed Luczak to continue asking about the Signal chat.

FBI agents were surveilling Flores-Ruiz before his arrest and they watched him leave for court in the morning, Lucker testified.

Luczak asked Lucker why agents didn’t just arrest Flores-Ruiz at a traffic stop. She said she didn’t know.

During opening arguments, prosecutors contended courthouse arrests are “routine” and “safe,” largely because the people involved have to go through courthouse metal detectors.

In contrast, defense attorneys said Dugan was in “uncharted waters” when it came to the presence of ICE near her courtroom.

A President Joe Biden-era directive largely prohibited immigration enforcement in or near courthouses, but Trump’s administration reversed that policy.

Local officials in the Milwaukee area have raised alarms about the courthouse apprehensions, arguing that ICE’s presence discourages immigrants from showing up to court.

At the time of Flores-Ruiz’s arrest, Milwaukee County Chief Judge Carl Ashley had been working on a policy regarding ICE in the courthouse, but that policy was still in draft form.

The draft policy indicated that ICE arrests could happen in public areas of the courthouse such as hallways, prosecutors said.

Later in the afternoon, the court heard from Deportation Officer Anthony Nimtz, a federal official who signed an administrative warrant known as an I-200 on April 17. That warrant called for Flores-Ruiz’s arrest.

Prosecutors seemed to be pointing to paperwork, including the I-200 form, as evidence that Dugan had attempted to interfere with a pending federal proceeding.

The final witness called Monday was special FBI agent Jeffrey Baker. Baker said agents gave a heads-up about their arrest plans to the court’s bailiff, and he said agents agreed to arrest Flores-Ruiz after his hearing. Baker said Dugan seemed “angry” when she directed to agents to talk with the chief judge.

Demonstrators outside show support for Dugan

Over 50 people gathered outside of the federal courthouse before the trial started Monday morning to show support for Dugan.

“Today, we’re here to bear witness,” said Nick Ramos, executive director of the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign, during a press conference. “Today, we’re here to show solidarity. And today, we’re here to say clearly, ‘Milwaukee will not accept intimidation in our courthouses.’”

Demonstrators chanted “free Judge Dugan” and “hands off Hannah Dugan” while one person held a sign that read “due process for all.”

“Judge Dugan is on trial today for daring to defend the most basic right of immigrants, the right to due process,” said Christine Neumann-Ortiz, executive director of the immigrant rights group Voces de la Frontera. “What we are witnessing today is an effort by this administration to intimidate other judges.”

Editor’s note: Evan Casey contributed reporting.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.