The students in Ms. Dillon’s sixth-grade class at Roosevelt Middle School of the Arts in Milwaukee wrote letters to Mayor Cavalier Johnson with questions and ideas about how to address the city’s surge in reckless driving.

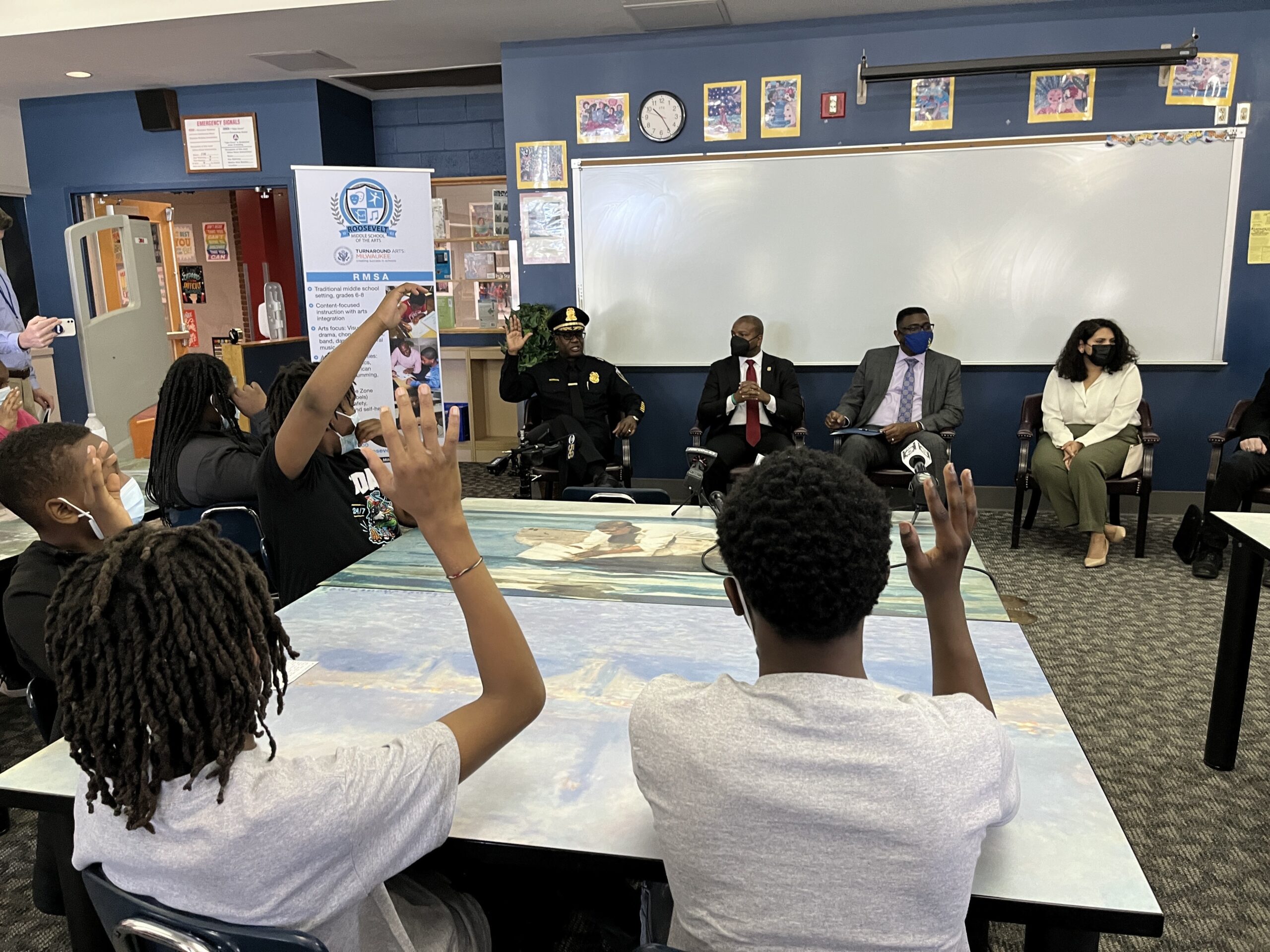

On Tuesday morning, he sat down with students in the school’s library to answer them.

“You engaged with your local government, and we listened,” Johnson said. “Your letters are the reason I’m sitting right here in your school, in front of you, right now — you guys did that, you guys have that power.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Milwaukee Police Chief Jeffrey Norman, Milwaukee Public Schools Superintendent Keith Posley and school board President Bob Peterson and Director Jilly Gokalgandhi, also responded to students’ questions.

Traffic fatalities have been on the rise for the last two years. Johnson also said that the latest city data he’s seen shows the same number of young people have been killed this year as there were by this time last year. In 2021, Milwaukee declared violence a public health crisis after seeing a rise in homicides — and violence has continued this year.

“We’re on pace to see a deadly year for young kids, for young people, and that to me is unacceptable,” Johnson said. “I don’t want to see that, just like none of you want to see that, either.”

Lamaya Calmese, a seventh-grader who wrote a letter to Johnson, said she was glad for the chance to hear directly from the city’s decision-makers

“It’s interesting to me that they came out here to talk to us, to provide us with information that we needed to know,” she said. “That’s why we wrote the letters out, and I was just grateful that they came out here to speak to us, because I wanted to know the answer and that’s what I got.”

Lamaya said she wanted to know if city leaders had plans to reinforce policing at schools, since she said she sees reckless drivers around Roosevelt at least once a week, and there are sometimes shootings nearby. She also said teenagers who are driving recklessly should face adult charges.

“They’re doing adult things, and they know their actions and they’re still not taking responsibility or being held accountable for it,” she said. “I am afraid of driving because of people that we have on the street — I just feel like I can be taken away, my life can be taken away from that.”

Several students wrote in their letters that they’d like to see parents held accountable, as well, when their children are caught driving recklessly.

Sixth-grader Sally Pritchett wrote that the legal driving age should be raised from 16 to 18.

“If that doesn’t work then charge both the parents and the kids ’cause I know if I got a ticket and not only me but also my mom had to pay for it, it wouldn’t happen twice, she can (guarantee) that,” her letter said.

Johnson told students that the city is taking several approaches to encourage drivers to slow down. In some areas, Milwaukee is adding “bump-outs” to curbs that make it harder for cars to get up on the sidewalk and to add distance between cars and pedestrians. He said they’re also hoping to add protected bike lanes and, in some areas, narrow the road to a single lane to make it more difficult for cars to weave through traffic at a high speed.

One of the sixth-graders, Jaheer Johnson, said his favorite idea was reducing lanes.

“In front of the school is big lanes, so narrowing it down to little lanes, I feel like that would help because now everybody’s going to be in one straight line,” he said. “I know some people are gonna hate it, but I feel like it’s the right way to do.”

Jaheer said he’s been in a reckless driving-related car accident.

“I remember passing out and not remembering nothing,” he said. “I didn’t realize we got hit, and it was the first time I was in a car accident and it was really scary, because I didn’t’ know if I was gonna lose my life or anything.”

That kind of firsthand experience — which other students mentioned in their letters, as well — is part of what drove social studies teacher Santanna Dillon to talk to her students about reckless driving.

“We decided to do this lesson because we see that reckless driving, teens’ reckless driving, as well as other reckless crimes throughout the city are affecting our students, in the way they learn and their mental abilities here at school,” she said.

Norman had students raise their right hand to be deputized as city ambassadors and pledge to help reduce reckless behavior.

“I promise to be involved in a reckless driving solution by speaking up when I see reckless driving around, so help me God,” he said, having students repeat after him. “So now you all made a promise, in front of TV cameras and in front of everyone in the room, to be a part of the solution.”

Mayor Johnson urged the students to make the effects of reckless driving on their safety clearer to the people they know who are driving unsafely.

“It takes folks who have those relationships at home to influence them not to do things that endanger the lives of young people, that endangers the lives of kids,” he said. “If you’ve got friends that you know that might be doing bad things, you can influence them — they listen to you much more than they listen to folks like us.”

Freddy Wright, another sixth-grader, said he thinks school and city officials have more power to discourage dangerous behavior.

“There’s only so much I can do,” he said. “If I see somebody doing something I can stop them or speak out on it, but it’s not all that much I can do myself.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.