In the year of reckoning following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, conversations about race, equity and belonging have gained momentum in some Wisconsin school districts.

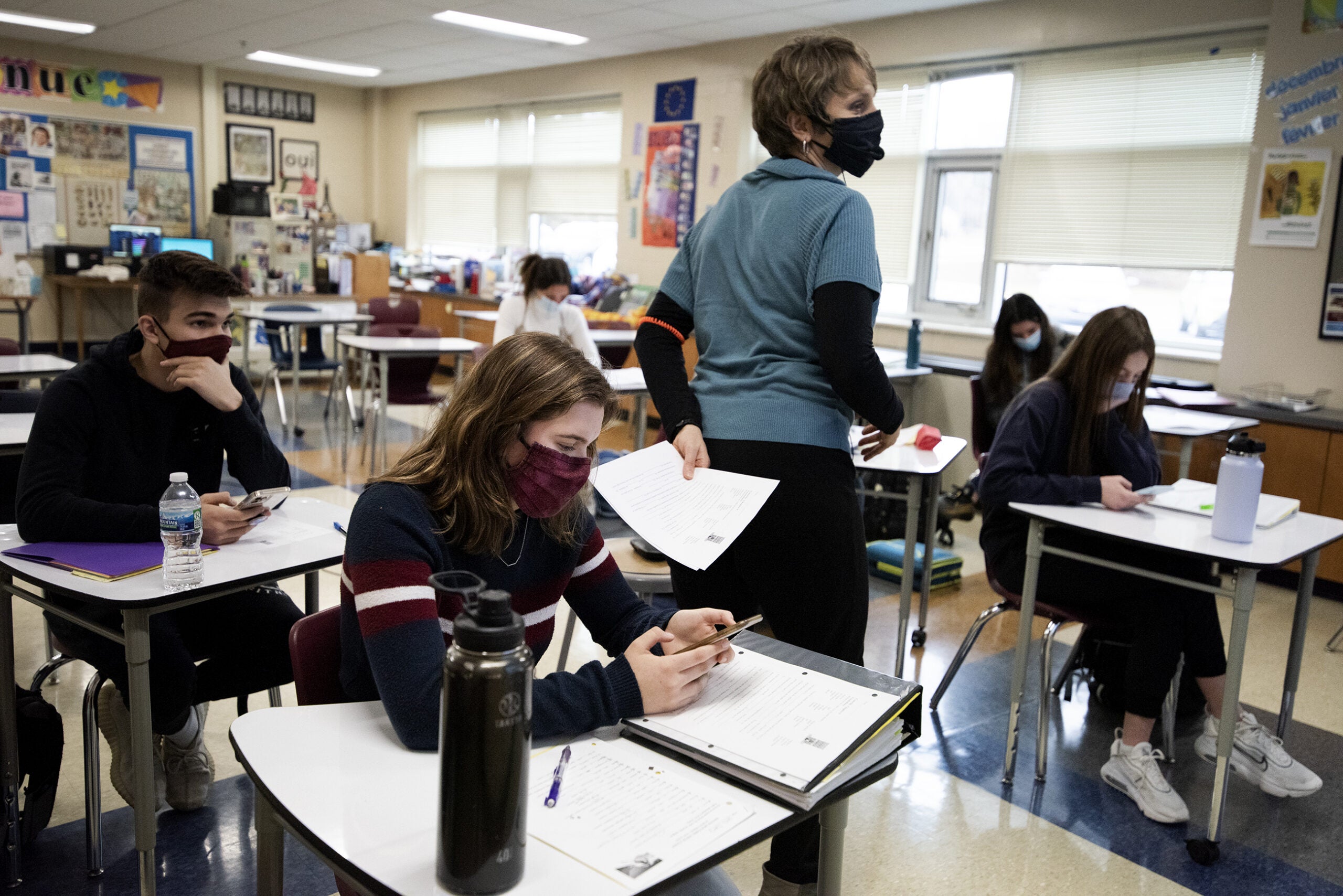

In several, that meant reassessing the presence of school resource officers and ending contracts with local police departments. Teachers have also grappled with how to surface these issues in the classroom.

At the same time, it’s sparked a backlash at the federal, state and school board levels, with lawmakers decrying critical race theory as being pushed by “woke mobs.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In a state where several school districts have been sued or found through the state complaint process to have racially hostile environments, and where the gap in educational outcomes between Black and white students has persistently been among the worst in the country, some districts have tried to shift the conversation toward equity — and been met with community uproar.

‘Equity Principles’ Spark Backlash In Elmbrook

In the Elmbrook School District, west of Milwaukee, the tension arose when the district’s annual strategic plan for the next year included a set of “equity principles” in response to feedback from a survey of alumni that showed 10 percent of Elmbrook students felt like they didn’t belong. The principles touch on diversifying the workforce and examining how teachers’ and students’ identities affect their experience in the classroom.

Chris Thompson, chief strategy officer at the school district, emphasized that the principles are not a curriculum or hiring quota, and would not restrict or reduce the advanced courses available or students’ opportunities to participate in those courses.

“Historically, this work has only been met with support from our board and our community,” he said at a Tuesday night school board meeting.

Thompson listed past equity efforts that included fundraising to help families who couldn’t afford internet gain access to it, removing course fees that put some classes out of reach for lower-income families, creating a universal four-year-old kindergarten program, and expanding college credit and AP course listings so more students would have access.

People who testified against the inclusion of the equity principles Tuesday night decried the efforts of a “woke mob,” called the efforts “cultural Marxism” and “critical race theory,” and worried the equity efforts would mean sacrificing the district’s high level of academic achievement and opportunities for nebulous cultural benefits.

“Our administration has gone rogue, and is undermining the board to create the most ‘woke’ education, which the community doesn’t welcome,” Emily Donohue, an Elmbrook parent and former write-in candidate for the School Board, told board members Tuesday. “We ask that you demonstrate integrity, to hold our administration accountable to educate our children in a manner reflective of our community’s values.”

One parent said he would pull his kids from the district if the School Board moved forward with the equity principles, while another pledged to run to unseat the first member up for reelection who voted to move the equity principles forward.

Ultimately, board members — some of whom expressed support for equity efforts in the district — voted 6-1 to remove them from its strategic plan, kicking it back to administration to find the right committee or working group to address the concerns community members had raised.

Equity Project Director: It’s About Who We Want To Be, Not About Who Is Right Or Wrong

While the term critical race theory has increasingly been invoked this year, and came up several times in the Elmbrook meeting, it’s often divorced from the actual definition. It’s a conceptual theory to help explain how inequality gets reproduced and maintained in our society, not an approach to demonize one racial group. It is usually taught at the graduate level, said University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Kevin Lawrence Henry.

“Critical race theory becomes a catch-all for anything that’s about equity and addressing diversity and racial disparities and inequality,” he said. “It becomes a kind of boogeyman or straw man about how we are indoctrinating children in schools, but in fact, critical race theory is not taught in the K-12 arena.”

He said the panic around critical race theory fits with historical pushback against efforts to extend opportunities to people who have previously been left out or discriminated against, such as after Reconstruction, the civil rights movement, movements for LGBTQ and disability rights, and the election of President Barack Obama.

At the school or district levels, Kathleen Osta, managing director of the National Equity Project, said fear and emotionally-charged objections to equity efforts are pretty typical, as well.

“It’s an uphill slog to help people see this not as a conversation about who’s right and who’s wrong, but really to extend the conversation to, ‘Who do we want to be now?’” she said. “If who we say we want to be is a place where all our young people have opportunities to thrive, that’s really what the heart of this is about.”

Starting With Common Values, Such As ‘Maximum Opportunity’

Osta said one of the ways her group gets past the backlash when it’s working to make schools more equitable and address issues of racism is by focusing on common values and the areas where people agree.

In Elmbrook, School Board member Mushir Hassan noted one potential point of agreement for everyone who testified both for and against the equity proposals: “The common thread that I see is that we want to make sure that every student has maximum opportunity,” he said. “I personally feel (the principles) allow us to get better at that. I recognize that there’s folks that disagree with me on this.”

Osta said that’s typically where her organization’s conversations at the school level start, as well.

“It’s not about mistreating white kids so we can treat Black and brown kids well, this is about creating communities and systems where every young person has access to what they need to grow, to learn, to thrive” she said. “We know that when young people see themselves in the curriculum, they’re more engaged, and they feel a better sense of belonging, and they’re more able to learn.”

‘This Helps All Students’

Henry used the example of the ramps constructed for buildings to make them more accessible to people using wheelchair — though created to level the playing field for one group that was historically shut out, they’ve had positive effects for others, for example, rolling suitcases or pushing strollers.

“When there are teachers employing multicultural or ethnic studies, or culturally relevant approaches to education, students’ test scores go up, we see that retention goes up, we see that student expulsion and suspension goes down,” he said. “When we’re making evidence-based decisions, not decisions that are based on ideology, it seems that the evidence is quite clear that this helps all students.”

Both Osta and Henry say the stakes are quite high.

When this backlash leads to bills that restrict teaching critical race theory, Henry said it poses a threat to the First Amendment that could tear at the fabric of democracy.

For Osta, who talks frequently with students dealing with racially hostile environments, not extending opportunities to thrive to all students puts their individual health and well-being at risk. It also gets schools stuck in the same practices that have kept Wisconsin at the bottom when it comes to Black-white achievement gaps and other disproportionate educational and disciplinary outcomes.

“I think increasingly — particularly listening to young people — it’s not working for so many kids,” she said. “We can’t keep things exactly as they are and expect the outcomes to change.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.