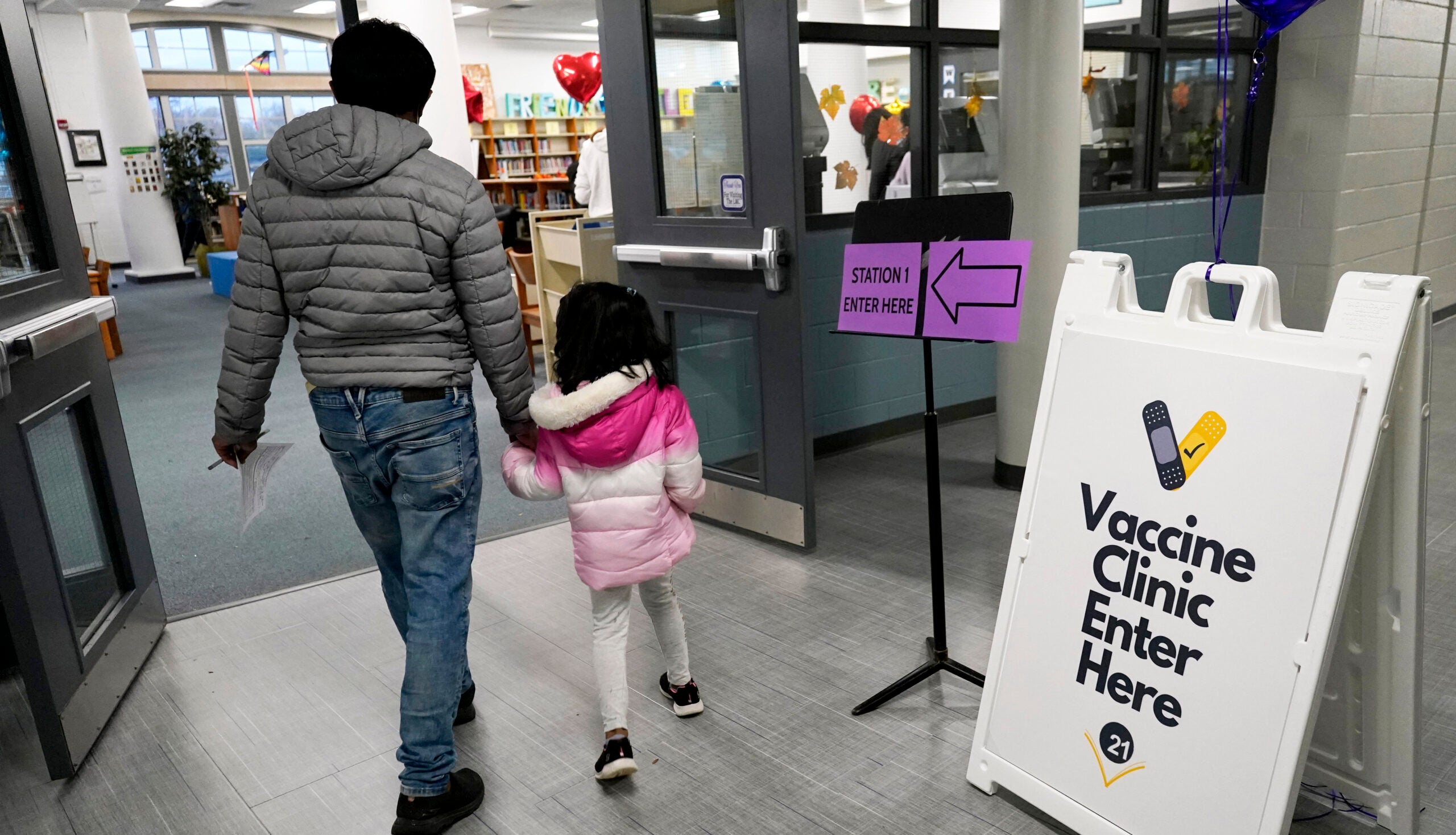

Doctors and public health workers expected demand for the COVID-19 vaccine would eventually wane in Wisconsin, but they didn’t expect it to occur so soon.

It has been a little over four months since the first shots were given to health care workers in the state. Now that everyone 16 years and older is eligible to get the vaccine, some might have difficulty accessing it or aren’t sure they want it. Others need more information or just want to wait.

What is often referred to as vaccine hesitancy is occurring in both rural and urban areas of Wisconsin.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Milwaukee Health Commissioner Kirsten Johnson said that vaccine uptake ranges from 90 percent to as low as 16 percent, depending on location. She made the remarks Tuesday as part of a Wisconsin Health News panel on Wisconsin’s vaccine rollout.

Nationally, polling has indicated rural Americans might be reluctant to get the vaccine, and vaccine providers in rural Wisconsin are anticipating getting enough people to accept the vaccine to provide community immunity could be challenging.

“I think we have our toughest work before us,” predicted Tim Size, executive director of Rural Wisconsin Health Care Cooperative.

Vaccination in rural Wisconsin has been 88 percent of what it is in urban areas of Wisconsin, according to Size.

A Kaiser Family Foundation poll in March found one in five adults living in rural areas of the U.S. said they “definitely would not” get the vaccine.

But the panelists, which also included Dr. Tito Izard from Milwaukee Health Services and Dr. James Conway, an infectious disease specialist with UW Health, generally agreed that conversations with trusted sources can have an impact in changing the minds of those unsure about getting the vaccine.

Izard said he doesn’t tell patients what to do. Rather, he talks to them about the consequences of getting the vaccine versus foregoing the shot.

“I’m asking them, ‘What is preventing you from making the decision (to get vaccinated against COVID-19),’” he said.

Conway said calling it vaccine hesitancy was an “oversimplification.” Instead, there’s a lot of what he called “vaccine complacency.”

“I think there are large numbers of people in areas of the state where people feel like things aren’t that bad,” said Conway.

He cautioned that COVID-19 hotspots can quickly can spread, making it all the more important to reach community immunity.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.