The land where Jan Penn and her husband Rick made their home in far northern Wisconsin checked a lot of the boxes when they bought it more than 40 years ago.

The wooded lot in the Ashland County town of Highbridge has sandy soil that’s easier to work with while growing a garden and frost generally hits a bit later with its proximity to Lake Superior. The two have built a life, raised their daughter, and cared for their horses and chickens on the 40-acre parcel. In December, they paid off the mortgage on their home and hoped to one day pass the land on to family.

“What this land has given us is beyond description,” she said. “It’s something deep in the soul that you experience.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

But, she fears their property may be part of plans by Canadian energy firm Enbridge to reroute its Line 5 pipeline.

Enbridge has been exploring alternative routes since the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa filed a lawsuit against the company aimed at shutting down and removing the pipeline from the tribe’s reservation. The line carries up to 23 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids per day from Superior to Sarnia, Ontario.

As Enbridge explores possible routes, the pipeline has created division among neighbors and communities over the path it may take. And, federal and state regulators have no authority to weigh in on the siting of the proposed line.

‘Things Are Going To Change … But What We Add To That Change As Humans Is A Significant Factor’

Snow is lightly falling on a January afternoon while Jan trudges through deep snow by Billy Creek. She’s found fingerlings in the Class I trout stream that flows along her property and empties into the Marengo River. The river is a major tributary of the Bad River Watershed that drains more than 1,000 square miles along the shore of Lake Superior. The Kakagon and Bad River sloughs — referred to as the “Everglades of the North” — lie at its mouth, comprising around 16,000 acres of internationally recognized wetlands.

[[{“fid”:”1147236″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”title”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”7″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBilly%20Creek%20is%20a%20Class%20I%20trout%20stream%20that%20flows%20into%20the%20Marengo%20River%2C%20which%20drains%20into%20the%20Bad%20River%20Watershed.%20Some%20tribal%20and%20community%20members%20say%20Line%205%20and%20a%20potential%20reroute%20of%20the%20pipeline%20threatens%20the%20region’s%20water%20quality.%3Cem%3E%20Danielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“7”:{“alt”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”title”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”7″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBilly%20Creek%20is%20a%20Class%20I%20trout%20stream%20that%20flows%20into%20the%20Marengo%20River%2C%20which%20drains%20into%20the%20Bad%20River%20Watershed.%20Some%20tribal%20and%20community%20members%20say%20Line%205%20and%20a%20potential%20reroute%20of%20the%20pipeline%20threatens%20the%20region’s%20water%20quality.%3Cem%3E%20Danielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”title”:”Billy Creek in Ashland County”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”7″}}]]

It’s part of the reason the couple rejected Enbridge’s requests to survey their land for a roughly 40-mile reroute of Line 5 running south of the reservation through Ashland and Iron counties.

Jan fears any spill could harm the region’s water quality.

“This is just a very unique place with some of the cleanest water in the world here, and so it’s hard not to love it,” she said. “Things are going to change. That’s true always … but what we add to that change as humans is a significant factor.”

While Jan hopes to preserve her land, others see the value their property may bring to their struggling families and communities as Enbridge seeks land.

Mellen Mayor Joe Barabe has been eager to work with Enbridge. The city reached a deal to sell land north of Mellen not far from Copper Falls State Park for $1 million as part of rerouting Line 5. If the pipeline is built, Mellen would receive another $3.25 million.

The city of roughly 700 is struggling financially after it installed a new lagoon at its wastewater utility that prompted sewer rates to climb roughly 73 percent for residents in recent years, Barabe said. He said Mellen owes about $1.2 million on the upgrade while an upcoming road project that includes more utility improvements may cost $1.7 million.

“Half of Mellen is fixed income. Those people won’t even be able to afford water when we’re done with them,” said Barabe.

Barabe believes the deal is the city’s only chance to get out of debt. And Ashland County will benefit from the agreement as well.

The county board recently voted to approve a quit claim deed to Mellen for the parcel the city wished to sell. Ashland County had previously sold the land to Mellen for $1 around 30 years ago with a restriction it be kept for public use. Enbridge has since agreed to maintain public access to the land as part of the deal except during construction and maintenance.

The board’s approval means the city can move forward with the sale, and Ashland County will receive $500,000 for allowing the deal with Enbridge. Without it, Enbridge said the company would be forced to pursue another route south of Mellen and neither the county nor city would receive any money, according to the board’s agenda.

Residents Have Mixed Feelings About Pipeline Route

Dozens of people filled the county board room and streamed out into the hallway of the Ashland County Courthouse to speak on the land deal during a Thursday, Jan. 30 meeting. In his appeal to the board, Mellen’s mayor noted that while the city and the Bad River Band are at odds over the pipeline, the city supported the tribe in its fight against a $1.5 billion iron ore mine proposed by mining company Gogebic Taconite.

“Just like the mine, Mellen is in the crosshairs,” said Barabe. “(Enbridge is) either going north of Mellen or they’re going south.”

Mellen residents like Peter Jokinen noted the financial stress on families.

“I’ve seen my water bills go up from $75 to almost $400. I have a family of six in the city... This saves us,” said Jokinen of Enbridge’s offer.

However, others urged county board members to think of the potential cost to public health and the environment if Enbridge continues to transport oil at a time when scientists are sounding the alarm about climate change. Ashland resident Ted Griggs called attention to the company’s track record.

“We’re being asked to trust Enbridge that their pipeline will work perfectly. It didn’t work perfectly in Kalamazoo,” said Griggs.

In July 2010, Enbridge’s Line 6B ruptured near Marshall, Michigan, contaminating the Kalamazoo River. The cleanup recovered 1.2 million gallons of oil and cost the company $1.2 billion.

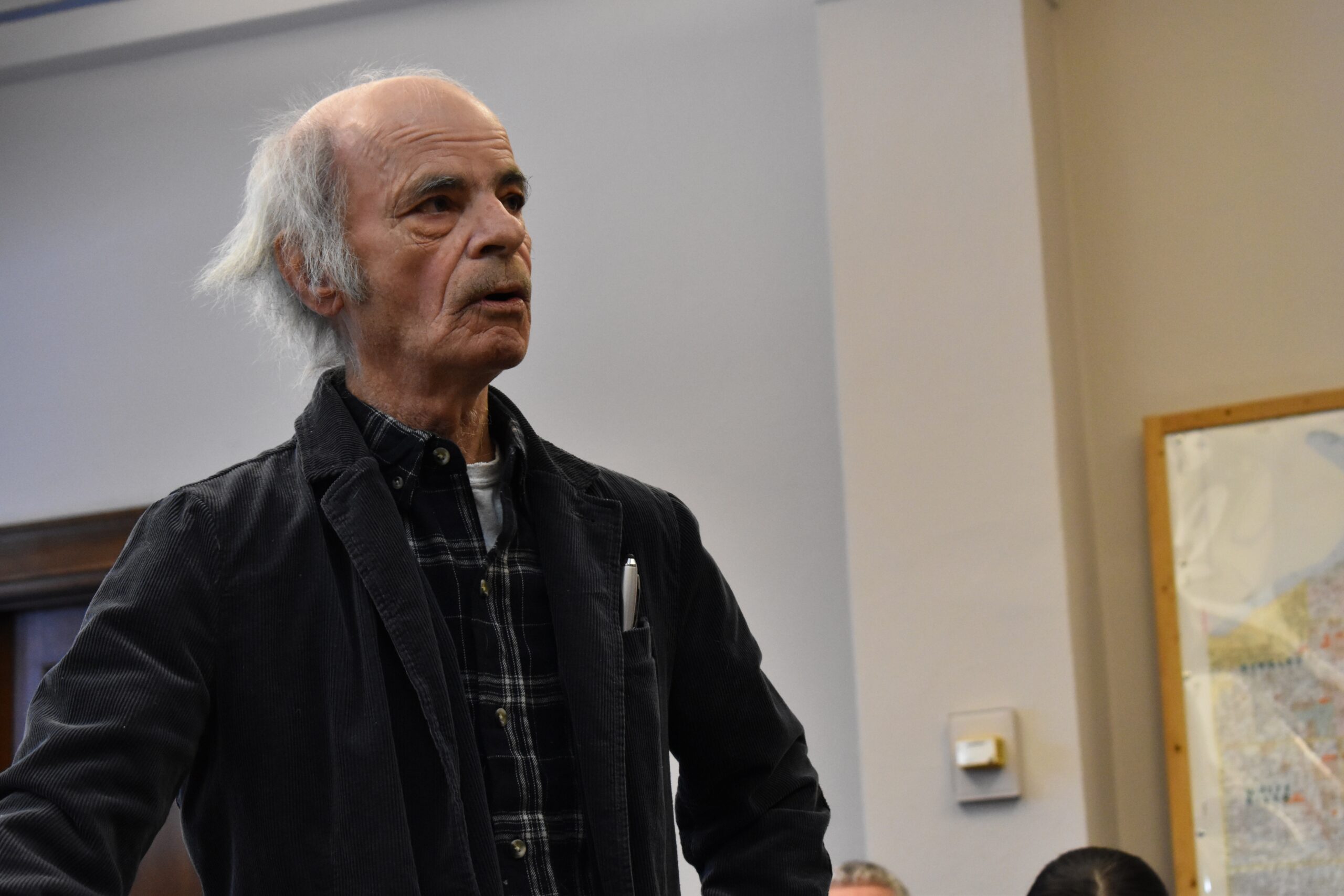

[[{“fid”:”1147286″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“alt”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”title”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”9″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EJuli%20Kellner%2C%20a%20communications%20specialist%20for%20Enbridge%2C%20listens%20in%20the%20back%20as%20Joe%20Rose%2C%20county%20board%20member%20and%20tribal%20elder%2C%20speaks%20out%20against%20the%20company’s%20pipeline.%20%22The%20record%20shows%20that%20Enbridge%20has%20a%20very%20poor%20environmental%20track%20record….In%20regard%20to%20a%20pipeline%20break%2C%20the%20question%20is%20not%20if%2C%20but%20when%2C%22%20he%20said.%3Cem%3E%20Danielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“9”:{“alt”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”title”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”9″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EJuli%20Kellner%2C%20a%20communications%20specialist%20for%20Enbridge%2C%20listens%20in%20the%20back%20as%20Joe%20Rose%2C%20county%20board%20member%20and%20tribal%20elder%2C%20speaks%20out%20against%20the%20company’s%20pipeline.%20%22The%20record%20shows%20that%20Enbridge%20has%20a%20very%20poor%20environmental%20track%20record….In%20regard%20to%20a%20pipeline%20break%2C%20the%20question%20is%20not%20if%2C%20but%20when%2C%22%20he%20said.%3Cem%3E%20Danielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”title”:”Board member Joe Rose speaks before vote”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”9″}}]]

On Line 5, there have been at least 29 spills since 1968 that have released more than 1 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids as shown by federal data, according to the National Wildlife Federation. Enbridge has said 206 barrels spilled while the company transported around 3.9 billion barrels of oil in 2018 — the most ever in the company’s 70-year history.

Bad River tribal officials urged the county to hold off on a decision, citing the threat the pipeline poses to the Bad River watershed. Tribal Chairman Mike Wiggins told board members everyone is getting “played” by Enbridge.

“The other scam that’s in play here is we actually have a choice. It’s either the southern route or the northern route,” said Wiggins. “No. They’re in the watershed, and they’ve been asked to leave.”

Board members debated the process for reviewing the land deal, questioning the urgency of the decision. Others noted state and federal agencies would still need to approve the company’s plans if it reroutes Line 5.

State Regulators Lack Authority To Review Routes

Enbridge’s relocation of Line 5 would require regulatory approval and a variety of environmental permits from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. But, the company is free to determine the path of its relocation — not state or federal regulators.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission oversees rate-setting for oil pipelines as part of interstate commerce, but it doesn’t have siting or permitting authority over oil pipelines. And, the Wisconsin Public Service Commission (PSC) has no authority over routing of oil pipeline projects, unlike in surrounding states.

A 2015 report by a Michigan task force found neighboring states Michigan and Minnesota must approve the location or route of any oil pipeline that’s constructed while Illinois allowed regulators to consider alternate locations for proposed projects.

In Wisconsin, the commission’s review of oil pipelines is also less stringent than its consideration of natural gas lines.

“The commission has jurisdiction to approve those, approve routing, approve the need for them,” said Matt Sweeney, PSC spokesperson. “Whereas in an oil pipeline, the commission only has jurisdiction in cases where somebody wants to use eminent domain to acquire land to build that pipeline. In those cases, the PSC has to find that the acquisition is in the public interest.”

Sweeney said commissioners have broad discretion when deciding whether a project is in the public interest.

The last time the commission allowed a company to use eminent domain for an oil pipeline project was in 2008 when Enbridge sought to add two pipelines to expand capacity to Midwest refineries. And language changes to Wisconsin’s eminent domain law in 2015 that Enbridge had a hand in crafting would give the company more legal footing to condemn property.

Jennifer Smith, Enbridge’s community engagement director, said the company plans to begin the permitting process with the PSC in the coming weeks. She estimates they’ve laid out about 70 percent of the pipeline’s path through option agreements with landowners.

“We have not yet started going back to say we would like to sign and complete those permanent easements,” she said. “That’s an activity that would happen as soon as we decided to move forward with the project and file the necessary permit applications.”

The relocation project would likely cost more than $100 million and create 700 jobs during construction, Smith said. She added Enbridge is confident it can obtain amicable agreements with landowners without using eminent domain. She noted the company withdrew an application with the PSC for its Line 3 replacement project after it reached easement agreements with all landowners.

However, a fight appears certain.

Attorney Erik Olsen with Madison-based Eminent Domain Services said the firm is representing clients who are likely to become involved in litigation over the proposed reroute. While Enbridge has offered an at least $24 million settlement to Bad River, the tribe has given no indication it intends to drop its fight to shut down the pipeline across its reservation.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.