More than a century ago, a cargo ship ran into a rocky outcrop while fog engulfed Lake Michigan.

Despite attempts to salvage that boat, its wreckage remained lost for 138 years.

That’s until Matt Olson, a tour guide in Door County, spotted something unusual.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Olson grew up playing in Lake Michigan, and he’s long been fascinated by sunken ships.

He also owns Door County Adventure Rafting, which offers boat tours of caves, shipwrecks and other Lake Michigan landmarks.

Last month, Olson saw a dark blob when looking at satellite images of an area of Lake Michigan near Rowleys Bay. So he went out on the lake with his boat, equipped with sonar and a waterproof GoPro camera.

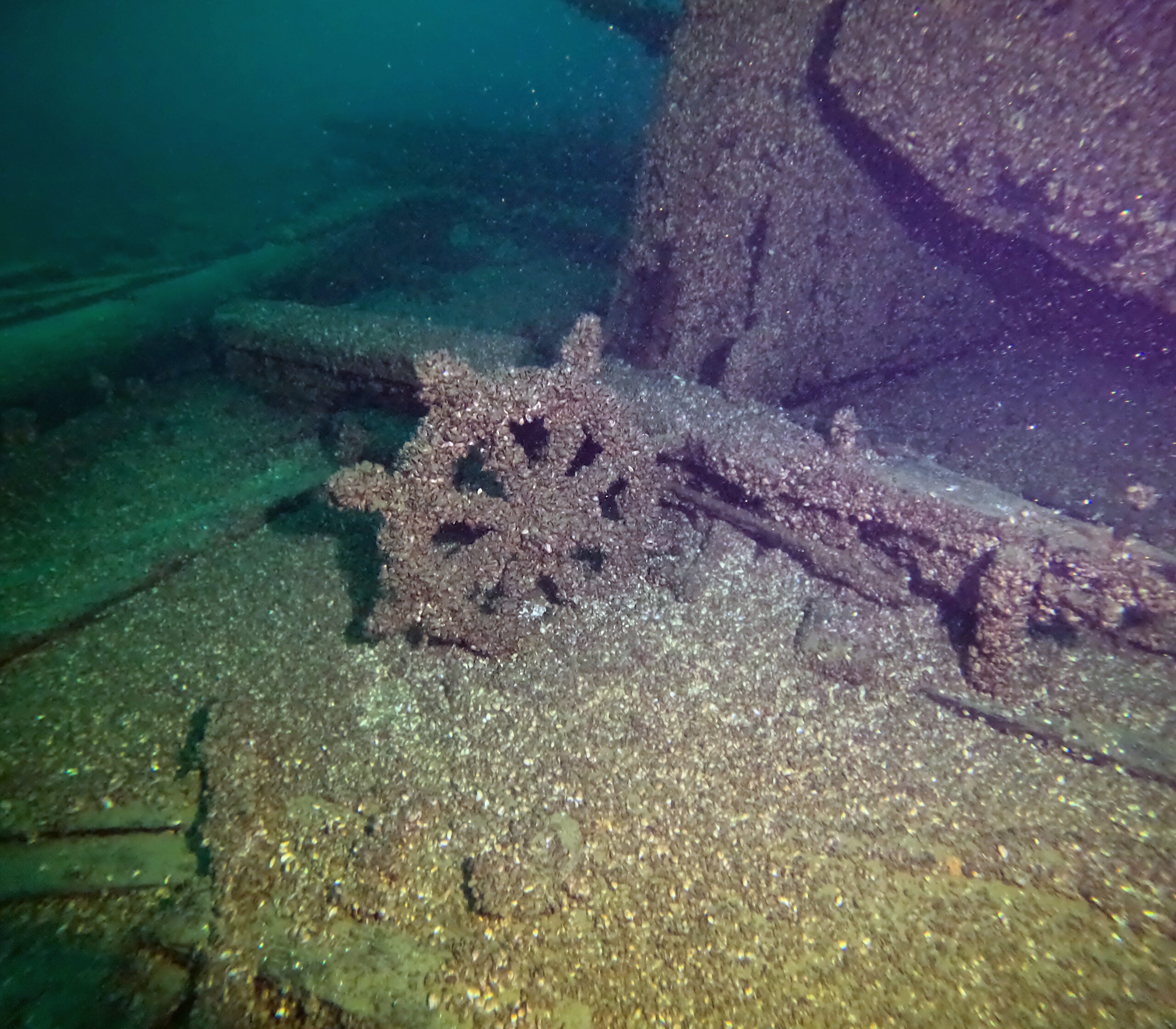

Beneath zebra mussels and fuzzy green algae, Olson could see the skeletal remains of a huge ship.

“It’s over 130 feet long,” Olson said. “When I saw how massive the wreck was, I was like, ‘How could no one have come across this at any point in time?’”

Olson was pretty sure the wreckage was what remained of the Frank D. Barker. That ship sunk in 1887, while en route to Escanaba, Michigan to pick up iron ore.

Olson reported what he found to the Wisconsin Historical Society, and archeologists there verified that it was the Barker.

No one died when the Barker sank. The ship’s captain and its crew took refuge on nearby Spider Island while they waited for the weather to improve.

At the time, newspaper accounts described the vessel’s whereabouts as closer to Spider Island. That may be why searchers were never able to find the sunken ship, despite salvage missions in 1887 and 1888.

Now, archeologists know that the wrecked ship has been resting under 24 feet of water, between the rocky ridges of a shallow area known as Barker Shoal.

It’s likely that Barker Shoal got its name from the sunken ship, said Tamara Thomsen, a maritime archeologist with the Wisconsin Historical Society.

The Barker was built in 1867. At the time of its wreck, it would have been worth more than $250,000 in today’s money, according to the Historical Society.

In some ways, Olson said it’s surprising that the Barker remained undetected for nearly 140 years.

But he also described Rowleys Bay as a quiet area. Boaters tend to avoid it because of a limestone outcropping — likely the same rock pile that led to the Frank D. Barker’s demise.

“There’s not too many boaters that go out from there, and it’s mainly just fishermen,” Olson said. “So I guess that’s why no one ever came across it.”

Soon after he first spotted the Barker, Olson took his wife and 6-year-old son, Magnus, for a snorkeling trip over the ship’s remains.

That experience was Magnus’ first time snorkeling.

“We put a life jacket and some goggles on him, and he swam around,” Olson recalled. “That was kind of a cool thing, you know, to have him in the water checking this shipwreck out that no one has seen in 140 years.”

The Barker is the third Lake Michigan shipwreck to be discovered by Olson. Last year, he found the Grey Eagle, a schooner that sunk in 1869. He also helped find a schooner called Sunshine, which also sank in 1869.

The Barker was “one of the last big Door County finds” to remain undiscovered, said Thomsen, the maritime archeologist.

During her dives down to explore the site, she’s been struck by the sight of the massive, but ruptured, wood vessel.

“It’s like a football field filled with oak,” Thomsen said. “The entire ship is sort of filleted open, and a lot of the deck machinery is still there. It’s just really amazing. It’s almost like looking at a puzzle, because, you know, everything is there. It’s laid out. The sides have split open but you can, in your mind, kind of put it back together.”

The Wisconsin Historical Society plans to study the site further, as part of an archeological survey this May. That survey could allow the shipwreck to be added to the National Register of Historical Places.

In the meantime, archeologists warn that the site is protected by state and federal laws, making it crime to remove artifacts from the wreck.

The way Olson sees it, the wreck is part of a history that’s shared by Door County and all of Wisconsin.

“There’s a lot of interesting things potentially on this shipwreck, and it would be a shame if it got pillaged by people looking for souvenirs,” Olson said. “It’s important to protect and preserve these wrecks.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.