Missy Clark-Nabozny was 11 when she lost her grandfather in the sinking of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald. The Ashland resident remembers the wet snow whipping against the windows that night.

She and her sister Chrissie, who was 10, stared at a picture of the boat on the television set.

“We both were just staring at the screen, like, ‘What’s going on?’” Clark-Nabozny said. “My mom was just freaking out — very upset, sobbing.”

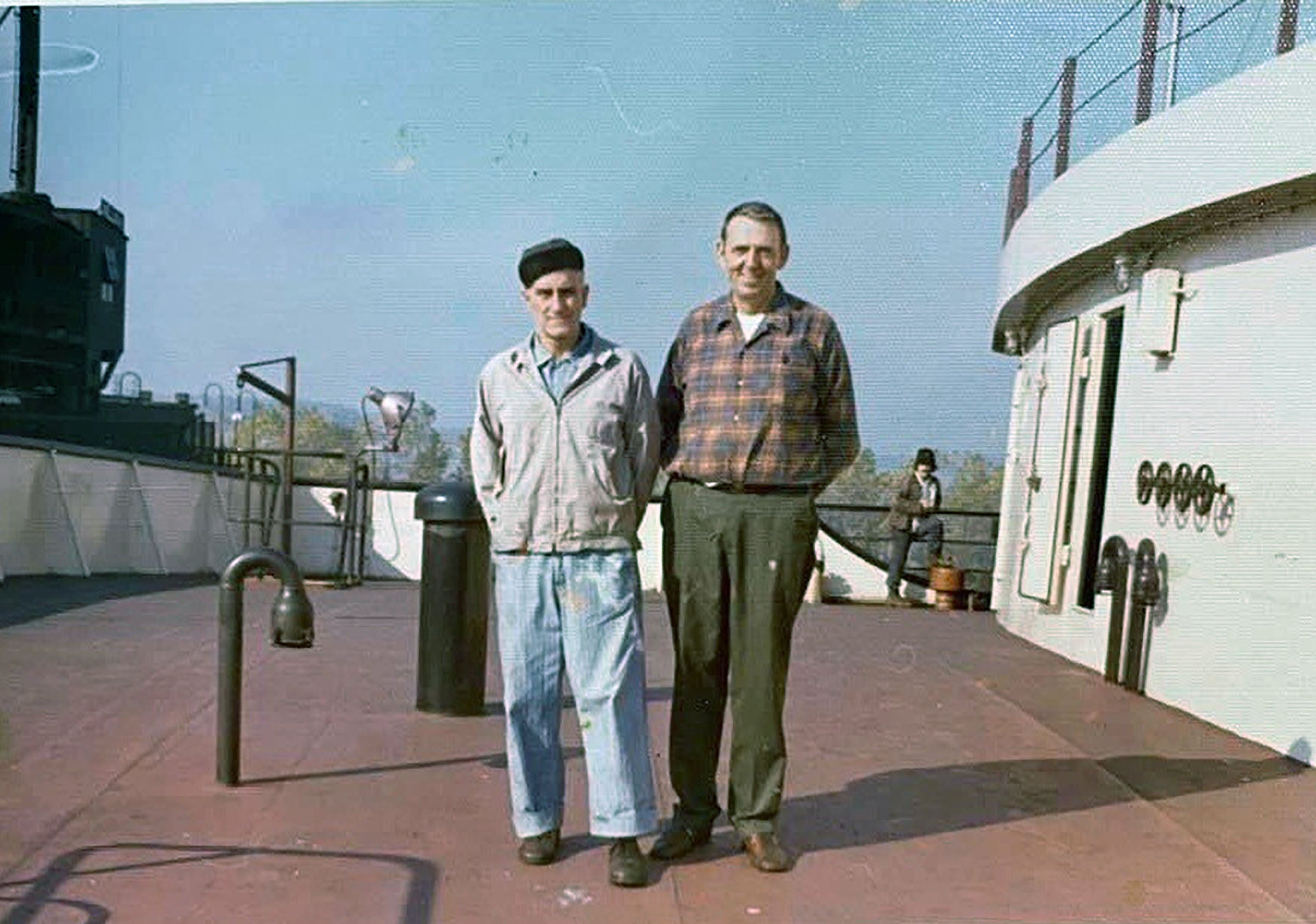

Her mother, Patricia, was the eldest of three children born to John Simmons, a wheelsman from Ashland who had been sailing with the Fitzgerald from its first voyage. And, at 64, she said the trip was set to be his last before retirement.

Bruce Kalmon had also been watching TV when news came across that a 729-foot ore carrier had been reported missing. He knew that was the length of the ship his father, Allen Kalmon, was sailing aboard. His sister woke their mom. The kids were sent back to bed, but Bruce said they could hear her making phone calls half the night.

“There was uncertainty as to what was going on,” Kalmon said. “My mom was 38 years old and had five kids, and so you can figure what was going on in her mind.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

By morning, Clark-Nabozny said they knew the ship was gone.

“There was a lot of sobbing, a lot of crying. But it was quiet,” she said. “’Quiet chaos’ is what I called it.”

Clark-Nabozny and Kalmon were among family members who gathered in Washburn on Nov. 1 for a memorial dedication ceremony for the 29 crew members who lost their lives aboard the Fitz just ahead of the 50th anniversary of its sinking. Local artists Jamey Ritter and Matt Tetzner designed the 16-foot memorial — made from a tower that was part of the historic Ashland ore dock. A weathervane of the ship is mounted at its top.

The human tragedy of the ship’s sinking would be felt by thousands. Just a year later, the crew would be commemorated in Gordon Lightfoot’s folk-rock ballad, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” which became a global hit. Since the sinking, advancements in weather forecasting, regulations and technology have improved safety and reduced the likelihood of another disaster on the Great Lakes. Although, some assets that have improved weather observations may be at risk under proposed federal budget cuts.

‘When the Gales of November came early’

The storm that claimed the sailors’ lives, known as a mid-latitude cyclone, formed east of the Rockies and headed straight for the Great Lakes. It was typical of the so-called “Gales of November” that occur in the fall and winter, said Steve Ackerman, emeritus professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

As the storm was forming, the Fitz left the Burlington Northern dock in Superior carrying 26,000 tons of iron ore bound for Detroit on Nov. 9, 1975. Some accounts from shipping captains report calm, warm conditions for early November.

The National Weather Service predicted the storm would bring northeasterly winds. In the early hours of Nov. 10, forecasters upgraded its gale warning to a storm warning with winds as high between 48 to 55 knots, or 55 to 63 miles per hour.

The ship’s experienced captain, Ernest M. McSorley, had guided the vessel on a route further north than usual to avoid the worst of the weather. But the forecast was wrong, and the storm intensified, with winds coming out of the northwest faster than expected.

“By that time, the Fitzgerald and the other ship had changed what their route was, and they were caught in the worst part of the storm in an open lake area,” Ackerman said.

The crew of the Arthur M. Anderson, a Great Lakes bulk freighter, was the last boat in contact with the Fitzgerald, trailing close behind as waves pummeled both boats. The Anderson reported waves as high as 25 feet as the lake saw hurricane-like winds at times.

While the storm was rough, it wasn’t uncommon, and the Fitzgerald was relatively new. First launched in 1958, it was the largest ship on the Great Lakes until 1971. And it was sailing with an experienced crew.

But the Fitzgerald lost both of its radars and a fence rail in the storm, said Fred Stonehouse, a Great Lakes maritime historian. Two ballast tank vents had also been damaged, and the ship sailed with a list.

“McSorley was pumping. His boat had two pumps going, and the intention was to get the water out,” Stonehouse said. “The pump capacity wasn’t enough to handle the water flooding in.”

A U.S. Coast Guard report blamed the sinking on loose hatch covers that allowed water to flood the cargo hold, causing the ship to sink lower and take on more water. But Stonehouse said many theories exist: a fracture break in the hull due to poor design, a monster wave that overtook the vessel, damage from possible grounding near Caribou Island.

“It remains one of the mysteries of (Lake) Superior what caused that,” Stonehouse said.

In its final transmission to the Anderson, McSorley said, “We’re holding our own.” But shortly after 7:10 p.m., the Fitzgerald went down without a distress call 17 miles northwest of Whitefish Point.

Weather forecasting changes at risk under federal budget cuts

The tragedy would have a lasting effect on the Great Lakes shipping industry. Stonehouse said agencies, including the Coast Guard, made significant changes to inspecting vessels and required each vessel to have at least one survival suit for each crew member to protect from exposure to the elements.

Ackerman said the National Weather Service did a pretty good job of forecasting the storm. But forecasters weren’t able to benefit from the data that feeds weather observations and prediction models today, particularly from weather satellites.

“When the Fitzgerald sank, there (were) zero weather buoys on the Great Lakes. None,” Stonehouse said.

The first buoys on the Great Lakes were established in 1979. Now, there are currently around 130 buoys and stations that are tracking conditions on the Great Lakes, according to Steve Gohde, observing program team leader with the National Weather Service Office in Duluth.

Those assets are among nearly 140 active buoy platforms collecting information on the lakes, according to Shelby Brunner, science and observations manager for the Great Lakes Observing System.

“Following the wreck, the Weather Service and Coast Guard saw a strong need to deploy these and their purpose is to provide safety for marine traffic and the blue economy for everyday people who go out on the water,” Brunner said. “Weather forecasters have improved forecasts, and buoys have been continually added.”

The buoys are deployed by a network of university, nonprofit, government and other partners that is supported either partially or entirely by funding from the Great Lakes Observing System. But that funding would be zeroed out under President Donald Trump’s budget proposal for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Cuts to NOAA’s National Weather Service have already limited weather observations in some states. Ackerman noted that the Trump administration wants to scale back the next generation of weather satellites. He worries the cuts will hinder observations and satellites that have been critical for improvements in weather forecasting.

“We’ll be back to 1975,” Ackerman said. “Our weather forecasts just won’t be as accurate.”

A NOAA spokesperson said the Trump administration is prioritizing science over “agenda-driven projects designed to advance the climate change narrative.” The agency said the next generation of satellites will optimize weather monitoring and safety, “enabling NOAA to continue providing Americans with more advanced and accurate weather models.”

Families of lost crew members face grief in waves

Around 30,000 people have died in roughly 6,500 shipwrecks on the Great Lakes. But amid safety and technological improvements, no commercial ship has been lost on the lakes since the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The families left behind by the 29 crew members lost on the ship continue to face grief that comes in waves, said Missy Clark-Nabozny.

As time passes, she has focused on the good memories of her grandfather John Simmons, who she called “Papa.” She said he was a jokester and a kind person, though he was not a saint. He drank and hustled pool games all the time, but he often wore a suit and tie.

“Not too many people know who he is anymore. They know of him, but they don’t know him,” she said. “They don’t know that he had this killer smile, or that he giggled like a little kid…or that he was friendly to all the neighbors. He and Grandma walked everywhere together, and she would always hold on to his arm. I know that she lived her whole life missing him. He left a huge dent.”

Kalmon said his dad, Allen, taught him how to hunt deer and was a phenomenal fisherman who loved sailing. His father was the second cook on the Fitz when it sank. During the memorial dedication, Kalmon read a poem about how his world changed forever that day and the darkness that followed, saying, “Healing finally feels here.”

“After 50 years, I feel like I finally got a gravestone I can visit,” Kalmon said of the memorial.

During the Washburn dedication, a bell once again rang 29 times in honor of the lives that were lost.

“Every single one of them, not just the ones from here, are important,” Clark-Nabozny said. “They all had families, and they all matter.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.