Four months after Wausau opened a temporary night shelter for people experiencing homelessness, Police Chief Matt Barnes says the experience has shed light on both the complexity of the crisis and the resilience of the community that stepped in to help.

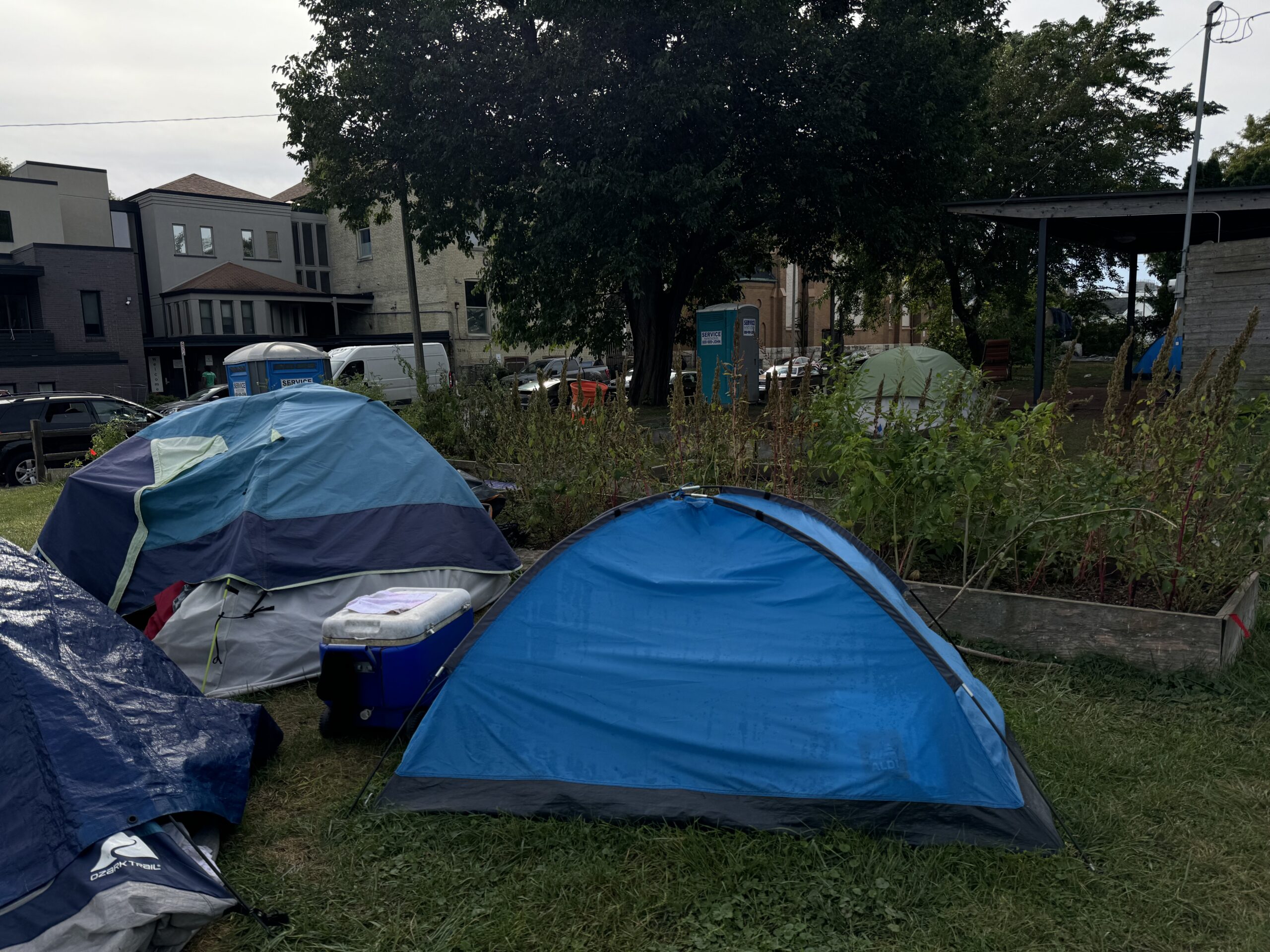

The shelter, housed at First United Methodist Church in downtown Wausau, opened May 1 as a joint city-county initiative. The move came after Catholic Charities’ warming center closed for the summer and no agency submitted a qualified bid to operate a longer-term program. Without the stopgap measure, Barnes said, the city risked seeing encampments reappear in parks and beneath bridges.

In a conversation on WPR’s “Morning Edition,” Barnes described the range of people who sought help. He was struck by the number of shelter guests who held steady jobs. Roughly 1 in 5 residents were employed, he said, often waking before dawn with the help of donated alarm clocks to make it to their shifts.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“When you say ‘homeless,’ it’s easy to lump them all into one big bucket,” Barnes said. “But that’s not the whole story.”

Barnes took a hands-on role in organizing the shelter, which provides beds for up to 60 people each night and is staffed by temporary employees trained in trauma-informed care and crisis de-escalation. Volunteers from across the community prepare food and provide supplies, while the city and county share the program’s roughly $130,000 cost.

Barnes acknowledged the initial fears among unhoused residents that the police department would run the shelter. But he said those concerns quickly faded as guests realized the program aimed to meet their needs rather than enforce laws. Two officers assigned to downtown parks, he added, have built trust by both holding people accountable for violations and connecting them with resources.

Community support, from donated appliances to daily meals, has been critical to the shelter’s success, Barnes said. The program is scheduled to continue through December, giving city and county leaders time to plan next steps for addressing homelessness in the region.

The following interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Shereen Siewert: What did this experience teach you about the daily realities of people living without stable housing?

Matt Barnes: I saw individuals who I struggle to see how, even with resources, they’re going to be self-sufficient. They’re not going to go get a job at a factory and rent an apartment. I just don’t think that’s possible.

Then, on the other end of the spectrum, I saw another individual who came in dressed very professionally. I thought they were a volunteer. I’m a trained observer, and I didn’t look down to see that they were pulling a suitcase. This individual did not strike me as mentally ill. They were not impaired, intoxicated, high, any of the things we often correlate with our unhoused population. It just makes you wonder, how do you end up in this situation when you’re so put together?

SS: You took a very hands-on role in helping launch this shelter. As you look back on those first days, what stands out to you most about the experience?

MB: For Wausau’s unhoused population it was either the choice between having shelter from May to October or not have a shelter, and we’ve seen what that looks like. When we don’t have shelter, we wind up with encampments in our parks and underneath our bridges. I said to myself, how hard can it be? And it turns out, pretty hard.

But we were fortunate that we have people on staff here who have spent a significant part of their careers working with the unhoused population. That was our ace in the hole. But a lot of things were hard, like knowing how much money it would cost to do it. I learned there are a lot of things you don’t think about that go into housing 60 or 70 people a night.

SS: Were you surprised by the number of people in the unhoused population who are employed?

MB: It was a significant surprise. The last measure I had was between 16 and 20 percent of the people in the shelter. They’re given alarm clocks, and they set them and they get up before everyone else and leave and go to work. We obviously have a significant percentage of that population who are mentally ill or have addiction issues and trying to figure each of them out is a puzzle. That’s a challenge. But if opening a shelter did anything, it really educated a lot of people who now have a better understanding of the challenges to the homeless population.

SS: If you had to do it all over again, is there anything you would have done differently?

MB: There are lots of little things we’d do differently but overall, I’m really proud of the staff and the community. We feed 50 to 70 people every night and house them and provide them with blankets and do our best to care for them. Food comes from volunteers in the community who show up every single day, seven days a week. We couldn’t do it without that help.

Catholic Charities, which runs a warming center during the cold months of the year, had a capacity of 30 beds. Every night, we were seeing them have to turn away a handful of people, maybe 10. So, we planned for a capacity of 60, doubling the space. And just this week we had a census of 67 one night. Understanding that and planning for it in a way that can maybe control that growth is important.

SS: How has the project affected the relationship between police officers and the people who are unhoused in the community?

MB: The homeless population was terrified that the shelter was going to be run by the police department. But those concerns lasted for maybe a week when they realized that what we were offering was meeting their needs. I think there will always be stress between police officers and the unhoused population because we are the enforcement arm for the city. When you behave badly or you break the law, we hold you accountable for it.

What’s interesting in Wausau is that we have two officers that are assigned to the downtown parks area and a significant amount of their work is associated with the unhoused population. They will hold you accountable if they see you violating the law or an ordinance, but they also connect with them and help get people the resources they need. There are numerous success stories that our officers are involved with. And, as I learned from spending time in the shelter and engaging with our guests there, no two are the same.

If you have an idea about something in central Wisconsin you think we should talk about on “Morning Edition,” send it to us at central@wpr.org.