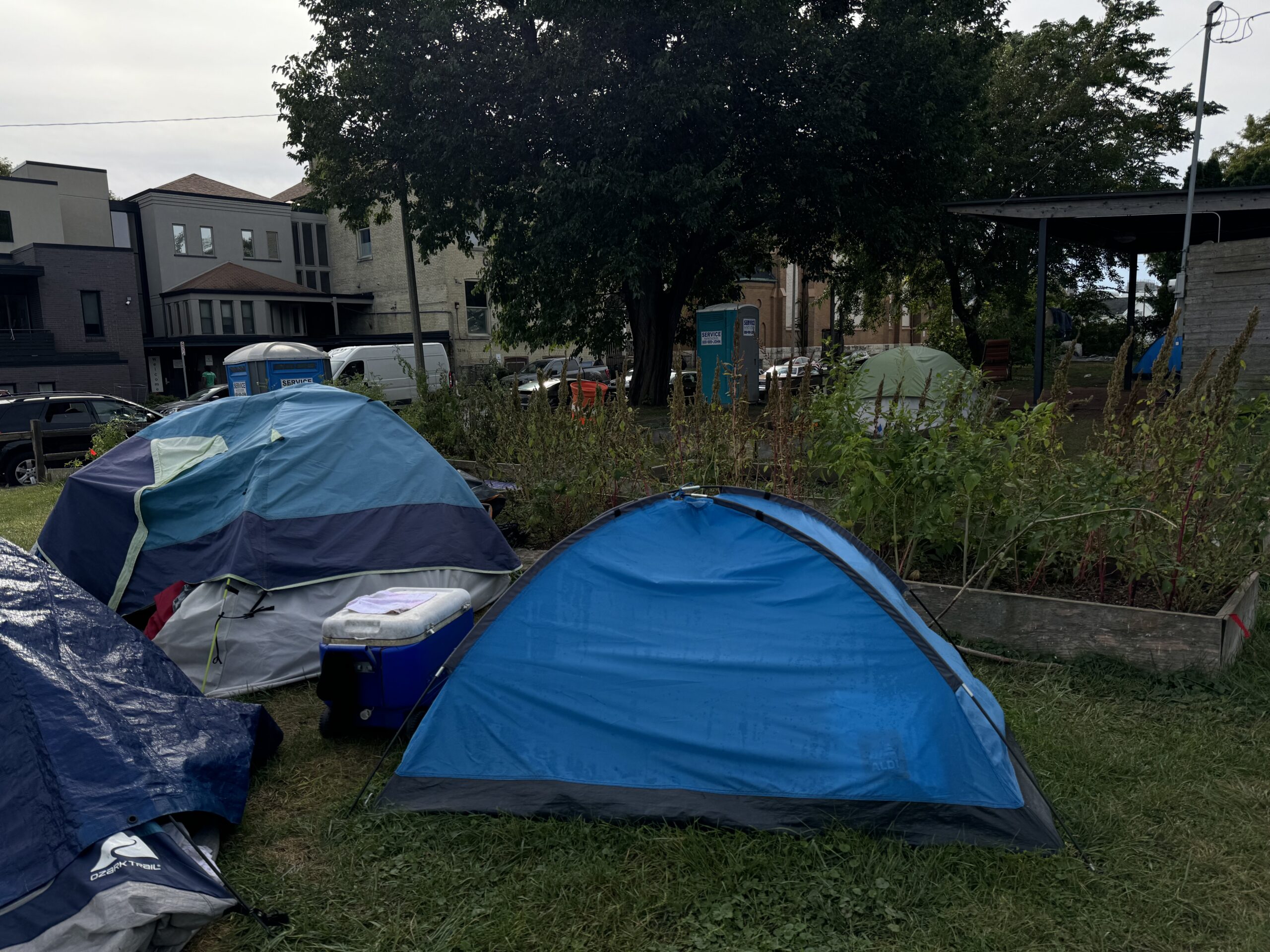

Late last month, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that would make it easier for states to remove unhoused people from street encampments.

In some cases, it encourages civil commitment for unhoused people with mental illness. It also makes room for civil commitment to an institution without their consent.

This comes after Trump signed a new law that would cut back funding for Medicaid and make eligibility changes to SNAP benefits.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

On WPR’s “Wisconsin Today,” Tami Jackson, public policy analyst and legislative liaison for The Wisconsin Board for People with Developmental Disabilities, said these actions could have compounding negative effects for the same groups of people.

“We really have kind of a perfect storm for people who are on fixed incomes,” Jackson said. “We’re worried about rising costs and keeping up their care during the federal policy changes.”

Jackson said there are a lot of questions that won’t get answered for quite some time — partially because the bill requires the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop regulations for how states should proceed, which aren’t expected until June 2026.

“So right now, things are stable,” Jackson said. “The state budget passed the cost to continue for Medicaid, and we’re in this kind of ‘wait-and-see’ period.”

Jackson recommended people update their contact information at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services so they can stay updated as things progress.

Jackson spoke in more detail on “Wisconsin Today” about how these federal policy and funding changes could affect the population of people with disabilities here in Wisconsin.

The following interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: What was your first reaction when you read the executive order?

Tami Jackson: This order really is rooted in very old ideas and assumptions, and they take us back to outdated policies that were abandoned for very good reason. This really shows a lack of understanding of who is homeless right now in our state and across the country.

One of the populations of people becoming homeless fastest are actually older adults and people with disabilities — for some of the same reasons. Many folks who are on fixed incomes, or are working as much as they can but are on a program like Medicaid that requires you to stay under a certain level of income and assets, really don’t have a lot of flexibility in their budgets.

And, if you’re a person who needs accessible, affordable housing because you have mobility equipment or other needs, there’s even less of that housing available.

Caregivers are also a factor in a growing rate of homelessness. When family members move in with somebody who needs care, sometimes they aren’t on the lease or the deed. If that person dies, all of a sudden, that (caregiver) has no place to live.

RF: This executive order encourages the use of civil commitment from state and local governments; involuntarily committing people to institutions. How would that work?

TJ: First of all, no one is immune from mental illness. So it really does feel like, if you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time, you could become subject to this. And it is unclear who makes the decision of who has a visible mental illness or something that looks like substance abuse. Is that a bystander? Is it law enforcement? And of course, (determining) who is visibly mentally ill is also a judgment call.

RF: This executive order very strongly pushes back against Housing First policies, and could affect funding for state and local governments. What does that mean for people with disabilities in Wisconsin?

TJ: In our population, we have the lived experience of what mass institutionalization as a policy approach has meant to individuals, families and communities. It simply is not a solution. It creates new problems.

Forcibly taking away people’s rights and putting them into institutions is demonstrably not effective. It’s not treatment. It doesn’t change the underlying causes of homelessness, and civil commitment is a really big deal.

There’s a reason it’s a court-involved process, because it’s the state deciding to restrict somebody’s freedom and take you and keep you in a place and decide if and when to let you out. I can’t underscore the seriousness of that as a policy approach, and what it could mean if it was applied to you or somebody that you love.

RF: What kind of Medicaid funding changes are you seeing that have you concerned here in Wisconsin?

TJ: The reconciliation bill did several major cuts. First of all, it took about $1 trillion over the next 10 years out of Medicaid. And people across the country are very concerned about what that will mean for state budgets and for people who rely on Medicaid for Health and long-term care.

Many people may rely on Medicaid, food assistance and housing vouchers to create a life that is stable. And right now, multiple aspects of those programs are in danger of being cut, which really leads to a big population of people getting hit from all sides at the same time.

A lot of the folks that we work with daily are saying, “Hey, if I get any less help than I have right now, the house of cards tumbles down.”

RF: What would that mean? Does that mean stopping medications, losing housing? What are some of the consequences you’re worried about here?

TJ: I think a lot of families are worried about all of those things.

We have lots of folks who need stable, reliable care over a long period of time. We have a lot of family caregivers who are providing most of that care and who are aging. So for our population, it really is a future worry of not only what happens tomorrow and next month, but next year and the next five years.