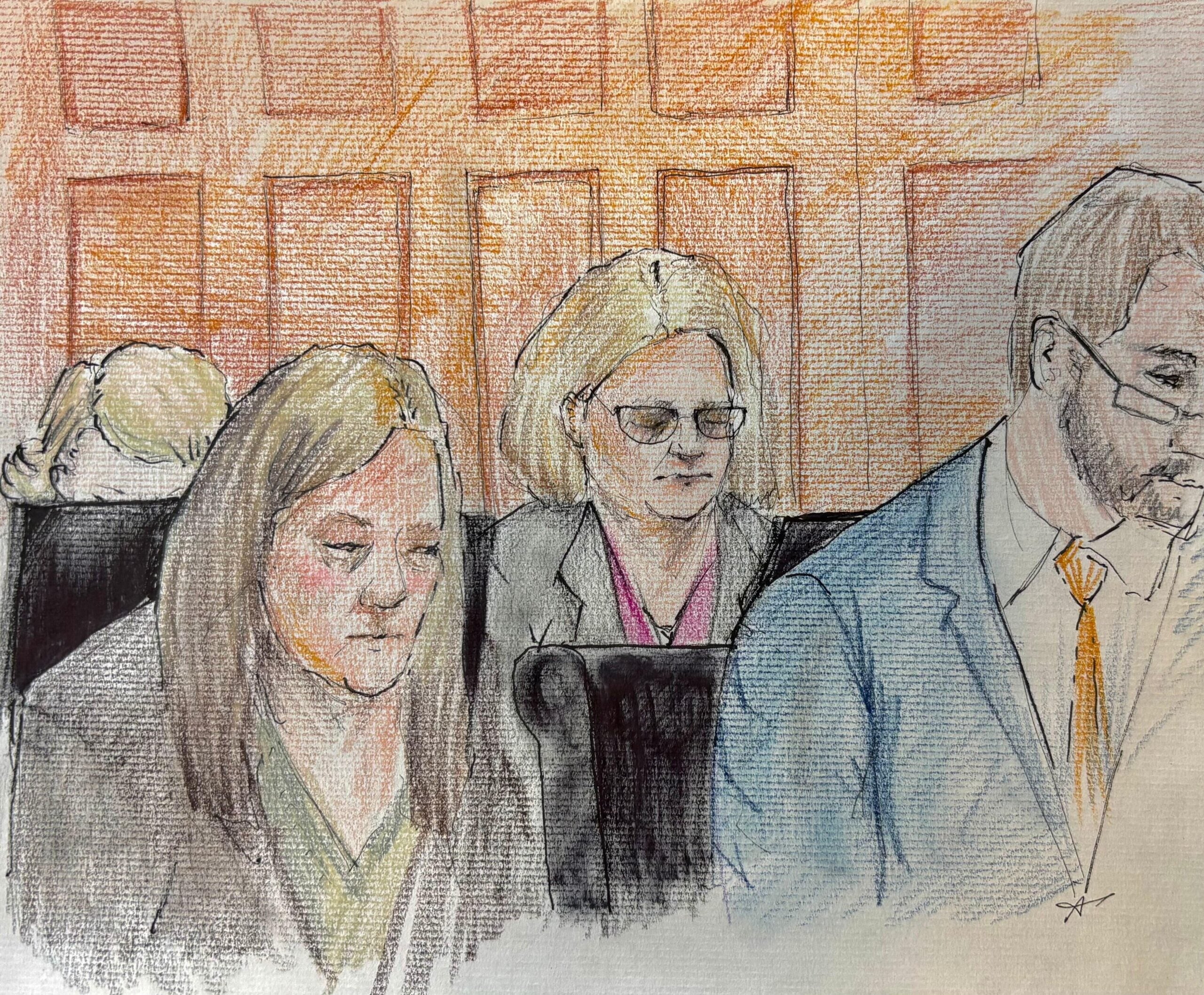

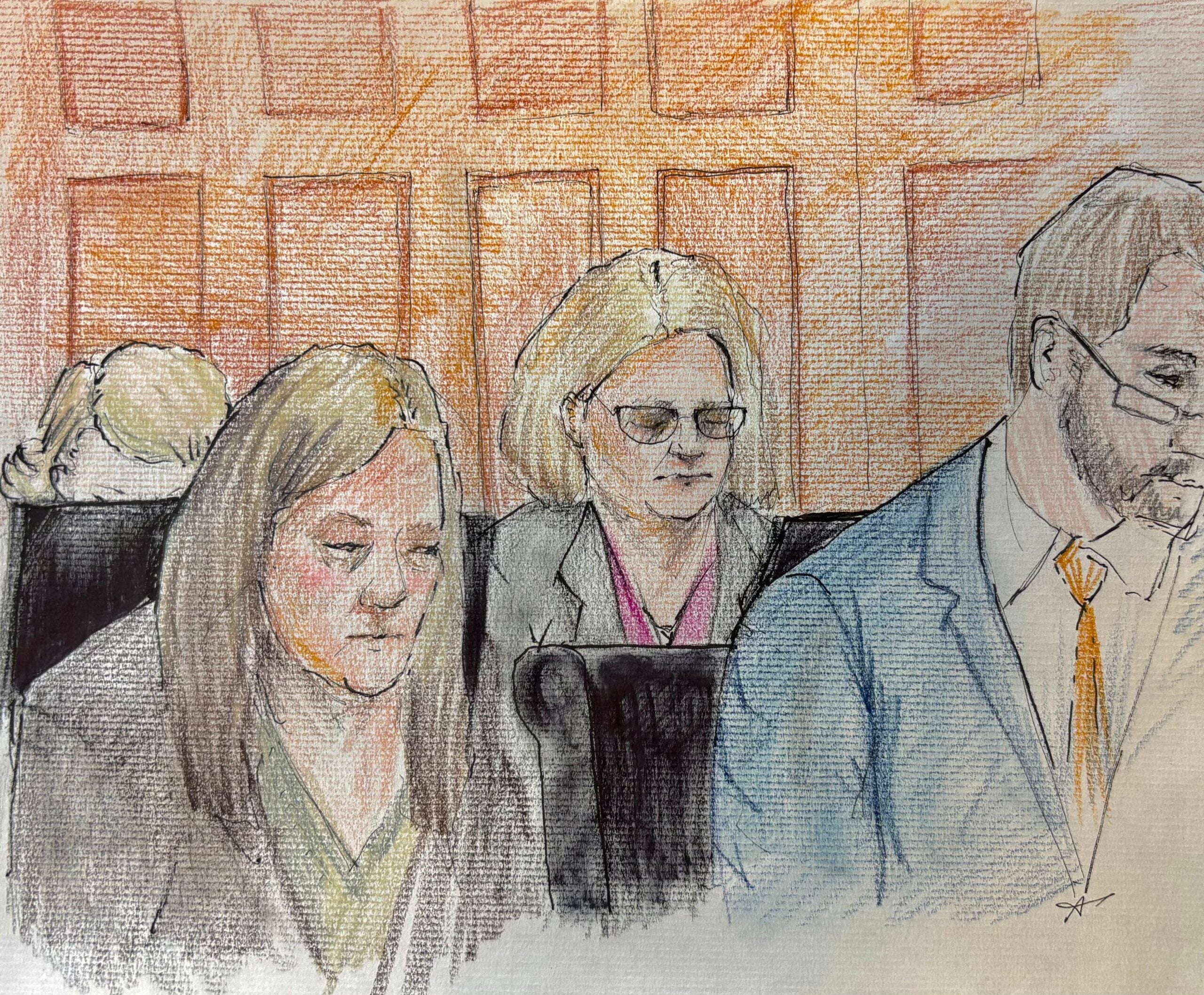

Attorneys for former Milwaukee County Judge Hannah Dugan are raising constitutional arguments as they try to overturn her felony conviction.

Dugan resigned from her judgeship early this year after a jury found her guilty in December of impeding a federal immigration proceeding.

Her legal troubles began on April 15 of last year when a she led a man named Eduardo Flores-Ruiz through a side door of her courtroom. That’s after federal agents showed up at the Milwaukee County Courthouse to arrest Flores-Ruiz for being in the country illegally.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

What type of warrant is needed to arrest someone inside a courthouse?

Those agents had what’s known as administrative warrant. It was signed by a deportation officer with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

In their latest legal filings, Dugan’s attorneys argue that type of warrant did not give ICE the legal right to make an immigration arrest inside the courthouse.

If courts accept that argument, it could have major consequences, said Howard Schweber, a retired University of Wisconsin-Madison professor and an expert on constitutional law.

“The ripple effect would mean that ICE agents should be barred from courthouses all over the country,” he said. “If the answer is yes, then all of these ICE operations in courthouses all over the country are unconstitutional.”

An administrative warrant is one signed by an official with a federal agency. That’s different from a judicial warrant, which is signed by a judge or magistrate. In most cases, a judicial warrant has been legally required to enter a private space like someone’s home.

But do officials need a judicial warrant to to arrest to make an immigration arrest at a courthouse?

During Dugan’s trial late last year, the consensus among witnesses seemed to be that ICE had arrived with what they needed to make arrests within public areas of the courthouse.

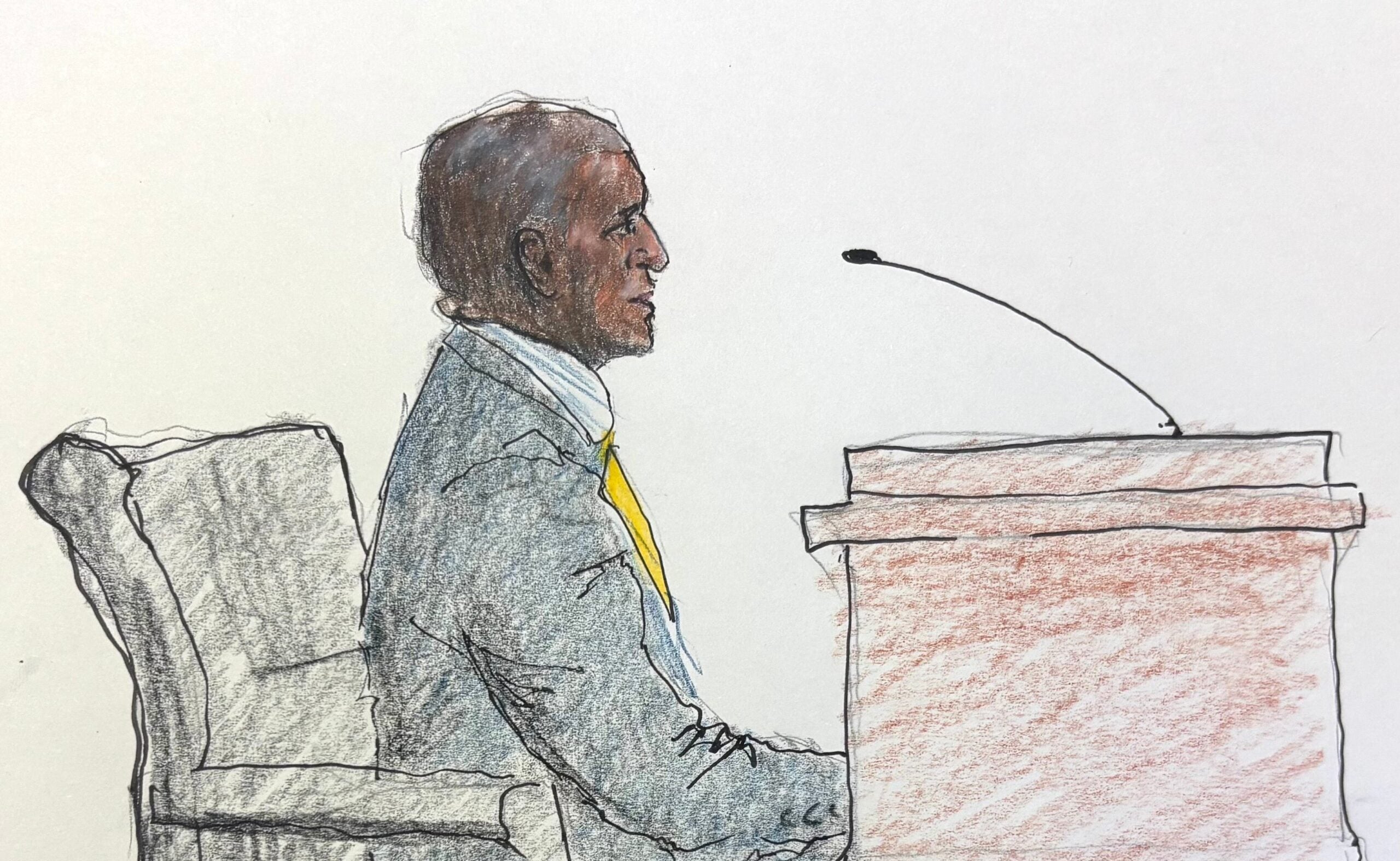

Dugan’s boss, Milwaukee County Chief Judge Carl Ashley, testified based on his understanding that judges and other county officials could not stop ICE from arresting someone within courthouse hallways. Ashley testified he told the agents as much when he spoke with them on April 15.

Dugan may have had a different understanding.

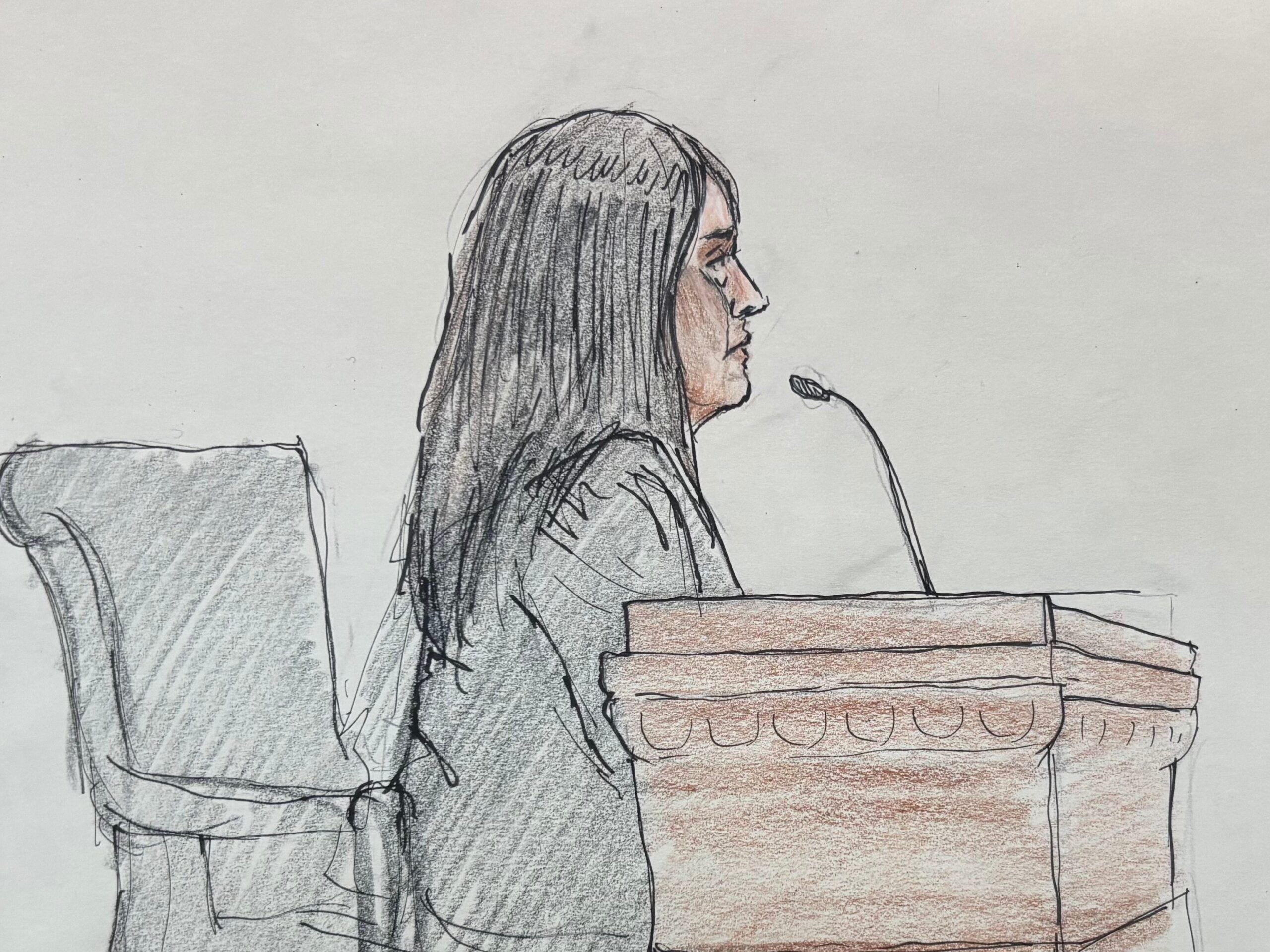

During the trial, another Milwaukee County judge, Kristela Cervera, testified that Dugan confronted federal agents in the courthouse hallway, asked them about their warrant and told them repeatedly that “it needs to be a judicial warrant.”

In the indictment against Dugan, federal prosecutors wrote that Dugan “falsely” told agents they needed a judicial warrant before Dugan directed those agents to the chief judge’s office to speak with Ashley.

But now, Dugan’s attorneys are claiming that, as established by a recent court case, there’s a “common-law privilege” that allows officials to bar civil arrests from happening at courthouses.

“Four well-reasoned district court opinions since 2020 (one as recent as November 2025) have applied that privilege to ICE arrests like this one in state courthouses,” Dugan’s attorney wrote.

That legal claim is “sweeping,” but it’s not “radical” or “far-fetched,” Schweber said.

“I don’t think it’s a slam dunk, although I do think it’s a strong argument,” Schweber said.

The types of warrants used by ICE have been in the spotlight recently, after two agents anonymously leaked a memo to Congress. That internal document reportedly tells ICE agents they can break into private homes without a judicial warrant, contradicting longstanding legal precedent.

Judicial warrants are intended to act as a check on the government’s executive branch, Schweber noted.

“It’s a separation of powers principle, essentially,” he said “That says we want someone who is not part of law enforcement to review law enforcement’s claim that they have an adequate basis for doing what they want to do. Administrative warrants violate that principle.”

Dugan’s attorneys ask for new trial

Dugan’s attorneys are asking U.S. District Judge Lynn Adelman to either overturn the guilty verdict or grant a motion for a new trial.

It’s “unlikely” a new trial will be ordered, Schweber said, although he does expect the verdict to be appealed and thinks the case could eventually reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

In their latest legal filing, Dugan’s attorneys resurrected several arguments they attempted to use before and during her trial.

They say nothing Dugan did was illegal and argue she was prosecuted for doing her job as a judge.

“Dugan files this motion as the first and only judge in United States history to stand trial on an indictment for wholly official, good-faith acts untainted by graft, corruption, or self-dealing,” her attorneys wrote in a motion filed late Friday.

In contrast, federal prosecutors have argued Dugan knew what she was doing was wrong.

They say she acted deliberately to obstruct federal agents on April 15 when she called Flores-Ruiz’s case out of its scheduled order, said his hearing would be rescheduled and ushered him through a side door that’s typically used by jurors.

Agents ended up arresting Flores-Ruiz later that day just outside the courthouse after chasing him on foot.

In December, a federal jury found Dugan guilty of impeding an official proceeding — a felony — but not guilty of a misdeamnor charge of concealing an individual to prevent his arrest.

In arguments submitted Friday, Dugan’s attorneys argued Adelman’s instructions to jurors were flawed because he gave differing instructions for interpreting each charge.

Specifically, he gave disparate directions about whether Dugan needed to have known the specific identity of the person agents were trying to arrest. That’s despite the fact that both charges described “essentially the same acts,” attorneys argued.

They’ve also argued Dugan cannot be found guilty of the felony impeding-a-proceeding charge because they say the administrative warrant out for Flores-Ruiz’s arrest at the time did not meet the definition of an official pending proceeding.

A date for Dugan’s sentencing has not ben set. Federal prosecutors have until Feb. 20 to respond to the latest arguments.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.