Early cartographers didn’t realize just how big Lake Michigan was.

Their inaccurate maps contributed to an armed conflict over state border disputes, known as the Toledo War, which led to the Upper Peninsula becoming part of Michigan and not Wisconsin.

Those maps are part of a new collection by cartographer Alex B. Hill, whose book “Great Lakes in 50 Maps” highlights the culture, ecology, infrastructure and economy of the area to tell a visual story about the Great Lakes and the people who live around them.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

He joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to share the common connections between the states and provinces around the water.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: How do you define what qualifies as being part of the Great Lakes region in your maps?

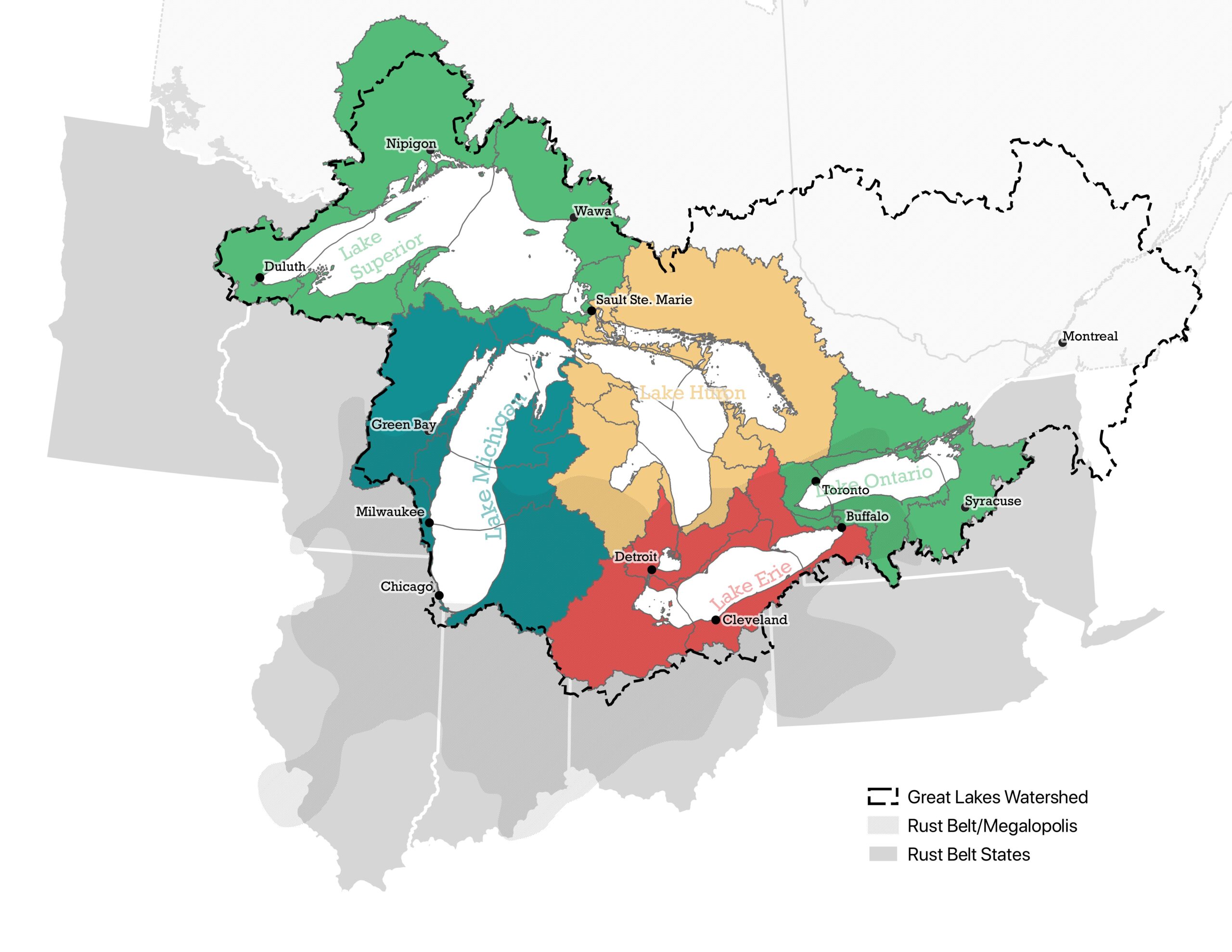

Alex B. Hill: That was a bit of a debate. Because, clearly, if you’re a state or a province that borders the Great Lakes, you’re included in that. But then the Great Lakes watershed extends a little further. And if you’re really thinking about the economics, it was billed as the Great Lakes megalopolis economic region, so you start reaching further south, away from the lakes.

So I chose to keep a broad definition. It still ends up being the same eight U.S. states and two Canadian provinces that have the most interplay with the lakes and interaction in the region.

RF: What kind of Indigenous connections did you find in the cultural history around the Great Lakes?

AH: I was most surprised that a lot of the names that we use currently are either adulterations or mispronunciations. Someone misheard the name, and now we call it this and spell it in a different way. But I was really surprised that a lot of those Indigenous names are still in use in different forms. That was a big piece of the book research, going back to those various European expansions in the “new world,” and the Indigenous connections with water were so significant.

RF: One of the big themes of the book is the environmental connections. What stood out to you across the region?

AH: When talking with people working in the policy arena or even just researchers at various universities, they kept talking to me about how the climate regions and the temperature zones were going to just keep moving north.

So in particular, there’s a map of sugar maples — where we get our maple syrup. Ontario has a lock on producing the most maple syrup, and they might end up producing all of it because that climate region is just going to keep moving north, and we’re going to lose a lot of sugar maples in the U.S.

RF: What kind of stories do those economic and infrastructure connections tell us about the region?

AH: That’s where that Great Lakes megalopolis comes in. The level of trade that we have going on between our various states and the economic benefit that the lakes provide, it’s in the billions of dollars. When we think about things like infrastructure, it’s easy to not think about how connected we actually are. Even with some of the more recent tariff discussions, parts of Michigan are supplied by Canadian power, and so we’re even doing international infrastructure sharing.

RF: You also include less serious maps, like one charting out reported lake monster sightings in the regions. Wisconsin even had a mythological octopus-like creature spotted in Devil’s Lake in Baraboo. What struck you about the stories you found?

AH: They call sturgeon “the dinosaur fish,” and then you have the muskie, as well. And if you saw those in a lake, you might think that there was a sea serpent in there, too. I might have to create the sea serpent road trip book or something after this because I was surprised that there were so many. There’s a lot of interesting lore around the Great Lakes. A lake in Indiana had an oversized turtle story. Somewhere along Lake Superior, there was a black panther sighting.

RF: People around the country might not think of the Great Lakes as a surfing hotspot, but we know of its popularity in Sheboygan and elsewhere on the shores of Lake Michigan. What did you learn in assembling the map of Great Lakes surfing spots?

AH: I was honestly surprised it’s an activity that you can do in any of the Great Lakes. The first story that I ever heard was a guy who was surfing in Lake Superior and had icicles stuck in his beard. I don’t know if I would choose to surf there, but it’s definitely gaining popularity. I don’t know if we’re going to get to California levels, but the Great Lakes have some pretty significant waves and swells. I guess the partner map to that is shipwrecks that really demonstrate how large the lakes are and the height that the waters can really get.