When Robert Birmingham moved to Madison more than 30 years ago to start his job at the Wisconsin Historical Society, he was “blown away” by how many effigy mounds were in the city and the surrounding lakes.

“That’s really what got me interested in finding out more and … explaining what a spectacular phenomenon this actually is,” he told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

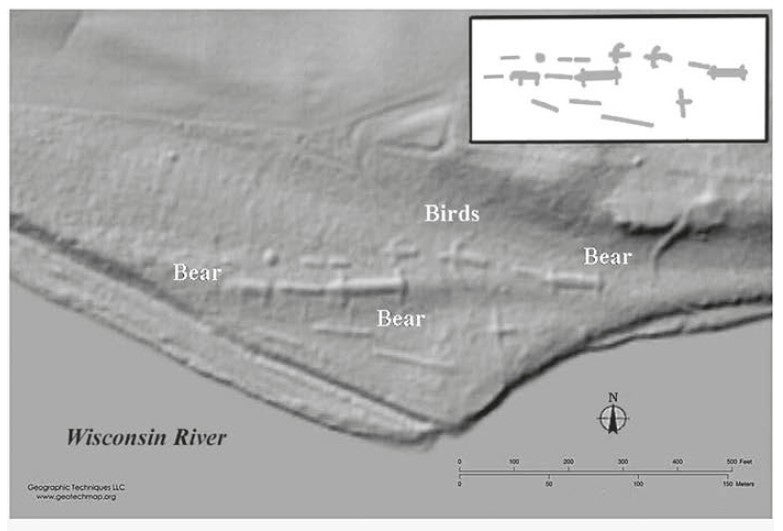

It’s not just Madison that is home to a lot of mounds. Wisconsin contains thousands of burial and effigy mounds — ancient earthen monuments built by Native American peoples more than 1,000 years ago in striking shapes of birds, bears and water spirits.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

You might have passed by mounds while hiking at a state park or walking through a cemetery or along a lake path, especially in the southern part of the state.

Archaeologists often have to travel far from home to find ancient artifacts, Birmingham said, but the mounds are a part of everyday life in Wisconsin.

“I live in a neighborhood here in Madison in which mounds are very common,” said Birmingham, who served as the state archaeologist from 1989 to 2004. “It’s not a matter of surprising exploration because they’re so visible and so accessible.”

Now, after years of research, Birmingham is out with a new book, “Ancient Effigy Mound Landscapes of Upper Midwestern North America,” which he wrote with Amy Rosebrough, the current state archaeologist.

Birmingham joined “Wisconsin Today” to talk about his archaeological research into mounds, what the mounds mean to Native peoples of the region and efforts to preserve them.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Rob Ferrett: You are interested in all kinds of mounds. This book focuses on the effigy mounds, though. What do we mean by effigy mound?

Robert Birmingham: An effigy mound is an ancient Native American burial mound made of earth that was shaped in the form of animals — for example, bears, canines of various sorts — but also supernatural beings that are important to Native people, even today: spirit beings like thunderbirds that create thunder — they’re associated with storms and lightning flashes out of their eyes, but they’re very good to human beings.

Another supernatural being very common in Wisconsin and other places is a long-tailed water spirit — that is what the Ho-Chunk call them. The Menominee call them great underground water panthers. Their form is, again, supernatural. They inhabit lakes and rivers, and they’re conceived of having a panther-like body with a very long tail and horns.

RF: The creation of these effigy mounds had kind of a heyday in terms of time. What is the time range we’re talking about for when people were building these effigy mounds?

RB: The effigy mounds themselves date between about 750 and 1100 A.D., so only a few centuries after the whole custom of building burial mounds faded and culture changed. After about 1200 A.D. or so, we don’t find Native people building mounds. They buried their dead in cemeteries, very much like the Euro Americans did.

Burial mounds in general started to be built thousands of years ago, a thousand years before effigy mounds. The first mounds, in fact, were large, round mounds, conical mounds that covered tombs with usually a lot of people buried. And then, almost suddenly, the custom changed, and people started to build these effigy mounds.

And the effigies, in our view, are not simply statues or earth sculptures. In the minds of the people who were making these, they were actually bringing these spirits back into existence at places where they dwell.

RF: And that’s one of the fascinating things in the book. You look into the minds, to the extent we can, of the people who made these mounds and the spiritual worldview being expressed in these mounds.

RB: Exactly so. The approach we take — and it’s an approach that’s only been around for a little while among archeologists, who are focused on data and artifacts and things like that — is called an ideological approach, in that it takes into account worldview and the religious beliefs of the people involved in certain phenomena … like effigy mounds.

We’re often talking about these mounds as comprising landscapes. Some mound groups are huge, and these landscapes are what we would call cultural or sacred or symbolic landscapes, with the caveat that when I say “symbolic,” again, we’re not talking about sculptures, but in fact, these forms are the actual spirits in the minds of the people. So it does require us to think as much as we can like the ancient Native people. And that information is accessible, of course, because Native people are still with us.

RF: There was a turning point some decades back when we stopped, or tried to stop, plowing these mounds under or building over them. How important has that preservation been?

RB: It has been spectacular. We have to start with the fact that in the past, largely in the 19th century and early part of the 20th century, most mounds were plowed away — mostly plowed but also destroyed. People did not have the appreciation as they do right now.

However, there arose one great individual named Charles E. Brown, who worked at the Wisconsin Historical Society. He was the director of the museum, and he, like myself later on, was impressed with so many mounds, and also very upset that these were disappearing.

He understood the archeological significance of these. So he and a group called Wisconsin Archeological Society made it their mission to save every mound that they could. Charlie himself even went on a new vehicle for reaching people, Wisconsin Public Radio, and gave weekly lectures talking about the importance of respecting Native American cultures and preserving their sites.

In fact, the effort to preserve effigy mounds, and mounds in general, was the first organized historic preservation program in the United States. … This was a well-organized campaign that was very successful after the fact that many had been so terribly destroyed.