When you think of Wisconsin fish, you may think of reeling in a prized walleye or musky. But a new book for middle schoolers tells the story of saving a fish that used to be common to Wisconsin waterways: the lake sturgeon.

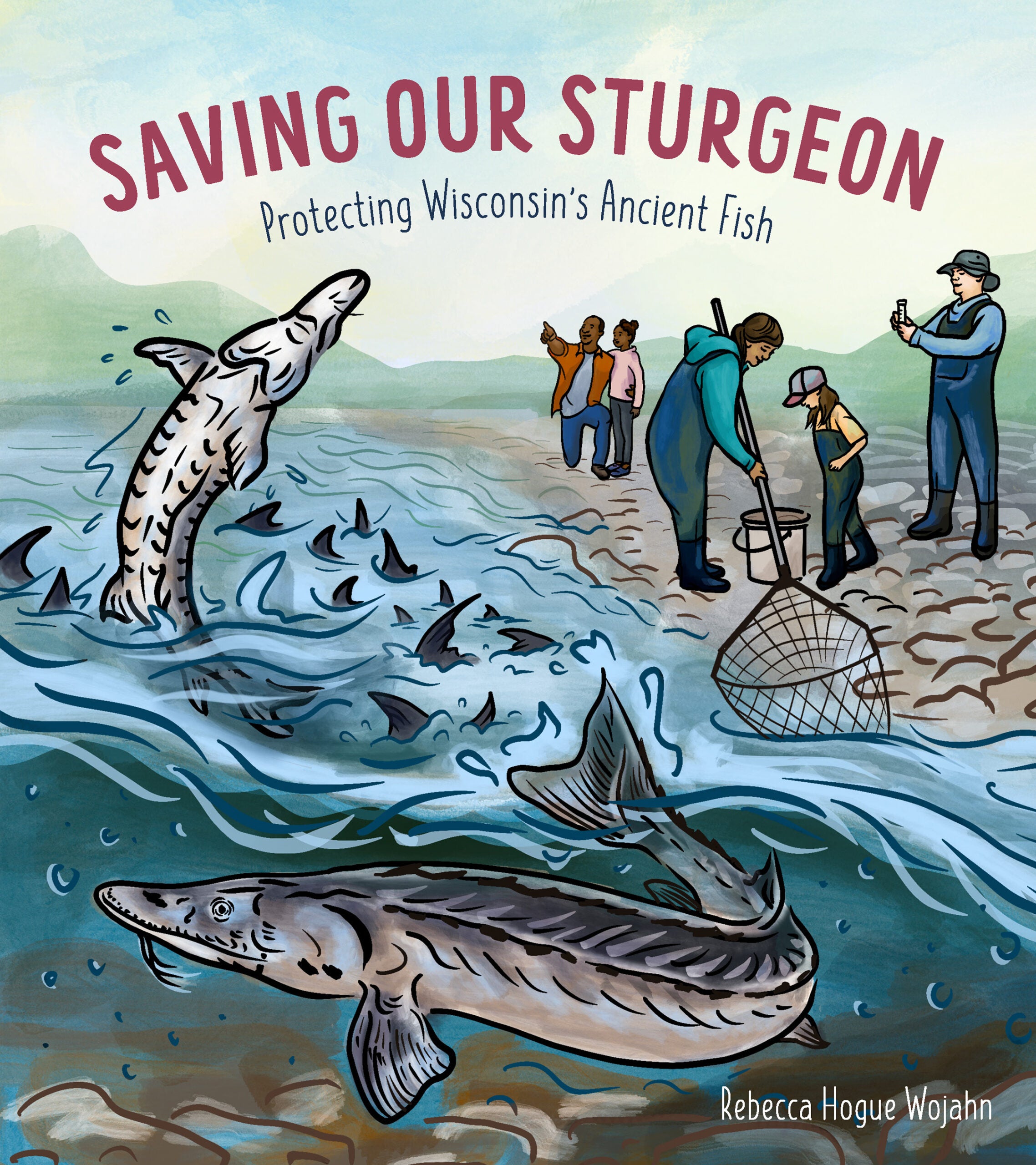

The book “Saving Our Sturgeon: Protecting Wisconsin’s Ancient Fish” documents the recent history of a species that numbered over 11 million prior to the 1800s, including how the fish nearly went extinct by the turn of the 20th century.

Rebecca Hogue Wojahn is the author of “Saving Our Sturgeon,” which is available Tuesday, Aug. 19. She told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that trouble for the species began in the early 1800s.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Once European settlers started arriving in Wisconsin … that’s when things started to shift a little bit,” Wojahn said.

Wojahn said early settlers viewed lake sturgeon as a nuisance fish and killed them off in large numbers to focus on other species deemed more valuable. But with the rise of refrigeration, attention turned back to lake sturgeon for a new reason: caviar.

“Suddenly it was seen as black gold in the state of Wisconsin,” Wojahn said. “Thousands and millions of fish were harvested for their eggs, and that took a huge toll on the sturgeon population.”

Lake sturgeon can live for up to 100 years and typically weigh anywhere from 30 to 80 pounds, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But they can grow much larger than that. In 2010, Ronald Grishaber of Appleton speared a record-sized 212-pound, 84-inch female sturgeon from Lake Winnebago.

Anne Moser, senior special librarian and education coordinator with Wisconsin Sea Grant and collaborator for the new book, told “Wisconsin Today” that settlers dammed many rivers and waterways lake sturgeon used as part of their spawning cycle.

Moser said the long lifespan of the species made it difficult for early settlers in Wisconsin to gauge the immediate impact of damming on the fish.

“When they built all these dams with no fish passages, we’re still seeing the effects of that today because they still have not completely recovered because of that,” Moser said.

But while many rivers and waterways saw declines in lake sturgeon, the Lake Winnebago region bucked the trend.

The dams that harmed sturgeon in other rivers inadvertently protected the Lake Winnebago sturgeon population, effectively sealing them into this system and protecting them from pollution and habitat loss occurring elsewhere.

“That’s why the story of that particular fishery is so important. Because it’s a closed system, (conservationists) can closely monitor it. They can get a lot of data and have a really good understanding of the science of how to protect lake sturgeon,” Moser said.

Conservationists studied Lake Winnebago sturgeon in the 1950s to learn more about the species and ultimately inform how best to increase the population of the fish.

After decades of attempts, the first successful experiment to hatch sturgeon took place in 1979. Sturgeon continue to hatch and grow in hatcheries today, including in a small town west of Lake Winnebago called Wild Rose.

Moser said one of the best ways readers can get involved in preserving Wisconsin’s lake sturgeon is to make a point to see them in person.

“To see these fish in front of you is just a remarkable experience,” Moser said. “In winter, go up to Lake Winnebago. Go to the registration tables where they’re registering the fish that are caught and to talk to people about their experiences. It’s unbelievable.”