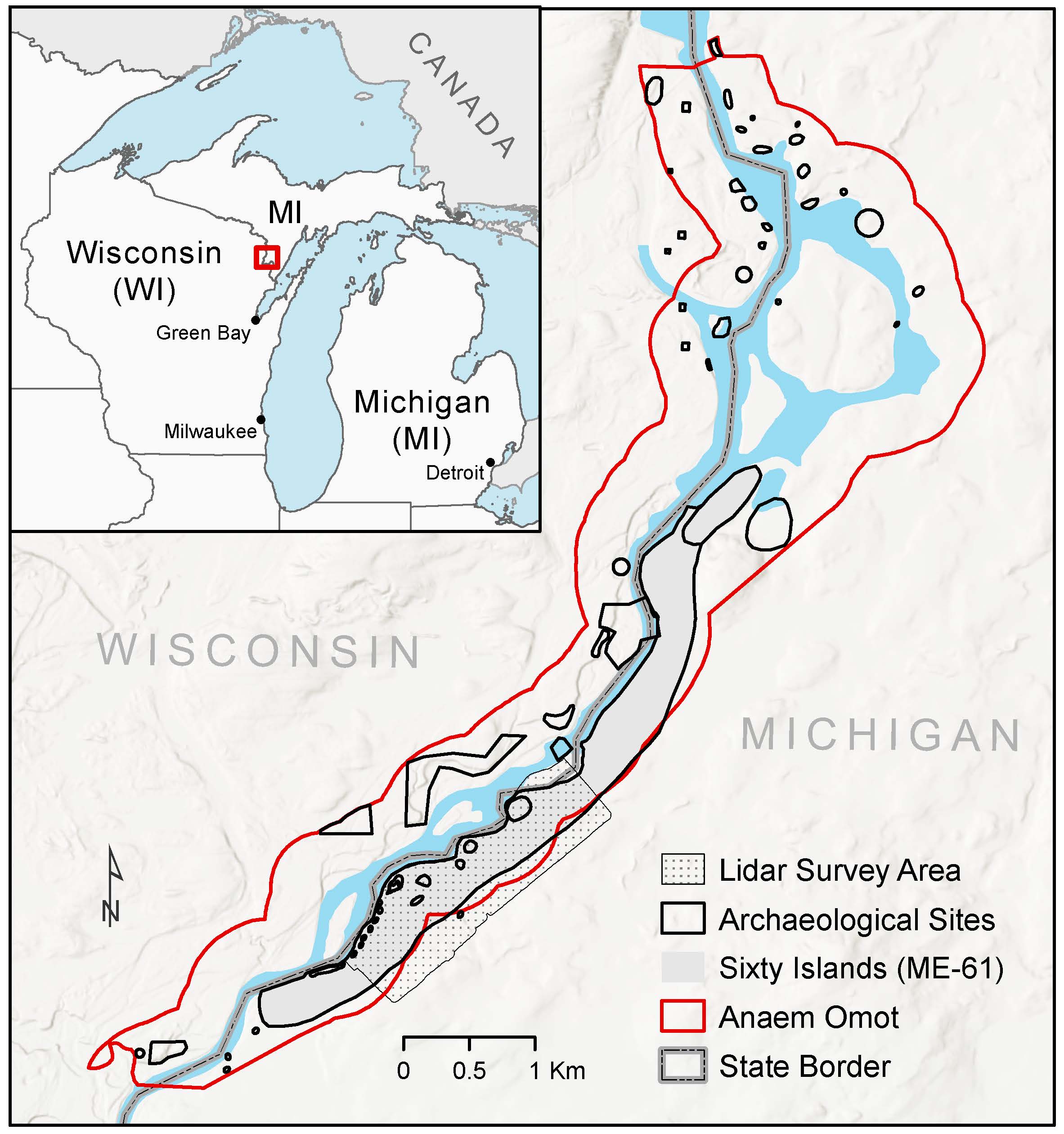

Along the Menominee River, on the border between Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, archaeologists have discovered what they believe to be the largest intact remains of an ancient Native American agricultural site in the eastern U.S.

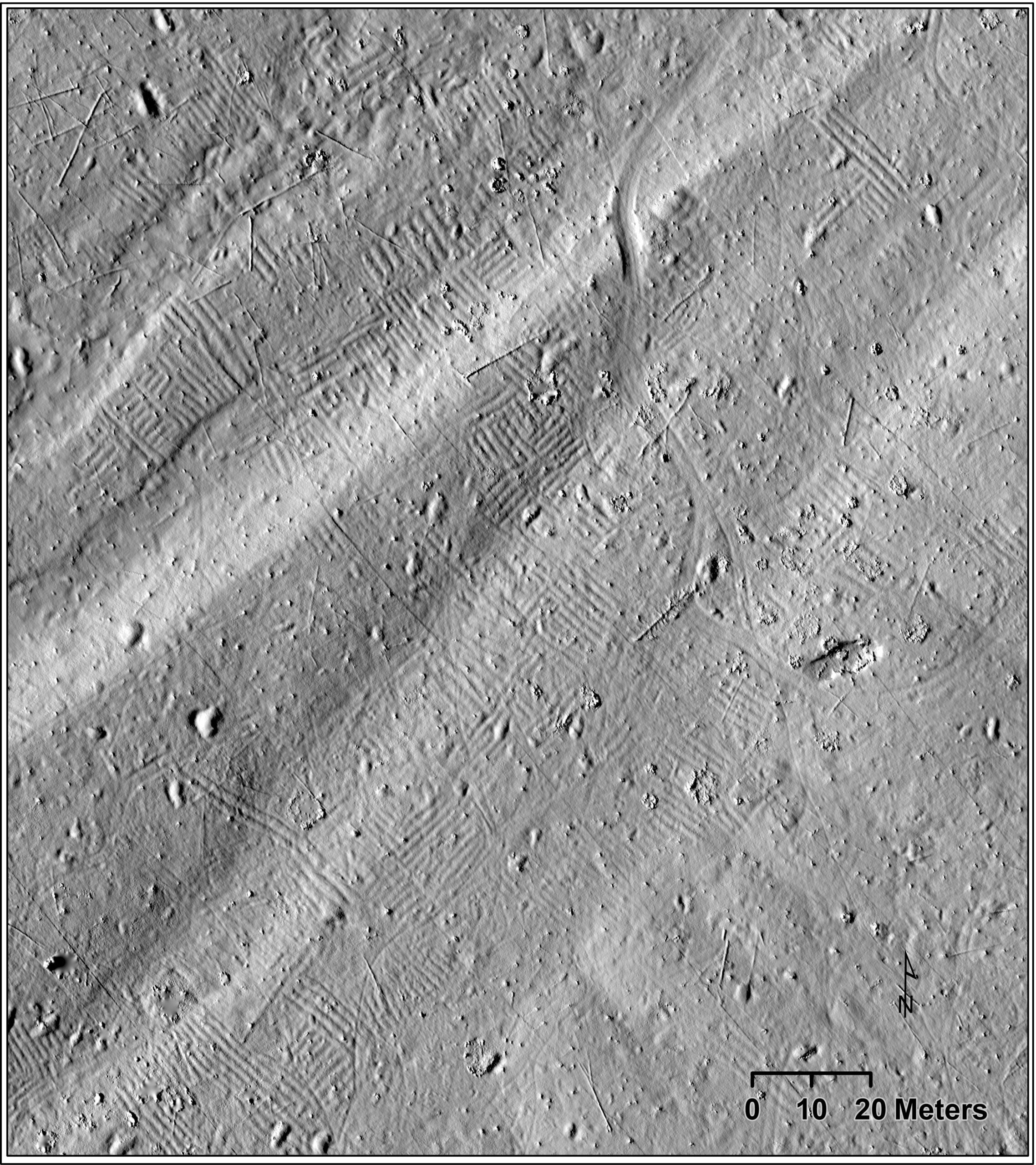

Using drones and laser technology to look at raised gardening beds along a stretch of the river, a team of researchers from Dartmouth College found that ancestors of the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin living 1,000 years ago were growing crops at a much larger scale than previously thought.

Madeleine McLeester, assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Dartmouth, led the research team in collaboration with Menominee Tribal Historic Preservation Officer David Grignon and the late Wisconsin archaeologist David Overstreet.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

McLeester told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that the discovery upends what archaeologists thought they knew about farming in precolonial North America.

“In this area, you would not expect to have such extensive agriculture,” McLeester said.

The archaeological site, known as Sixty Islands, would have been difficult to farm extensively, McLeester said. The corn, beans and squash typically grown on the raised beds would have been hard to cultivate so far north, especially because of the Little Ice Age. And ancestral Native American communities in the area were relatively small, making the size of the site even more puzzling.

In a report published in the journal Science, coauthor McLeester hypothesizes that, if there was a farming operation of this size in a small community under less-than-ideal conditions, those in the largest communities on ideal farmland were likely much bigger.

“As archeologists, we’ve grossly underestimated the scale of ancestral Native American farming in North America,” McLeester said.

Preserving the history of the Menominee

The Sixty Islands archaeological site is part of an area known as Anaem Omot, or “Dog’s Belly,” by the Menominee tribe. It’s an area of cultural significance, Grignon said.

“The Menominee people lived on the Menominee River for thousands of years. Our creation story took place at the mouth of the Menominee River, and we have several occupation sites up and down the river,” Grignon said. “A group of our people moved up to [Sixty Islands] and lived there for thousands of years.”

In 2023, Grignon and Overstreet, along with others from the Menominee tribe, successfully had the site listed on the National Historic Registry as a way to recognize the tribe’s history on the land. They also hoped that it would help in preserving the site and defending it against potential development.

Overstreet, who died in January, developed a close relationship with the Menominee after he began working with the tribe as an archaeologist in the 1960s. Grignon reflected on the precedent of trust and collaboration Overstreet helped set in the decades since.

“The relationship between the archeologists and the tribe was really good, and it still is today,” Grignon said.

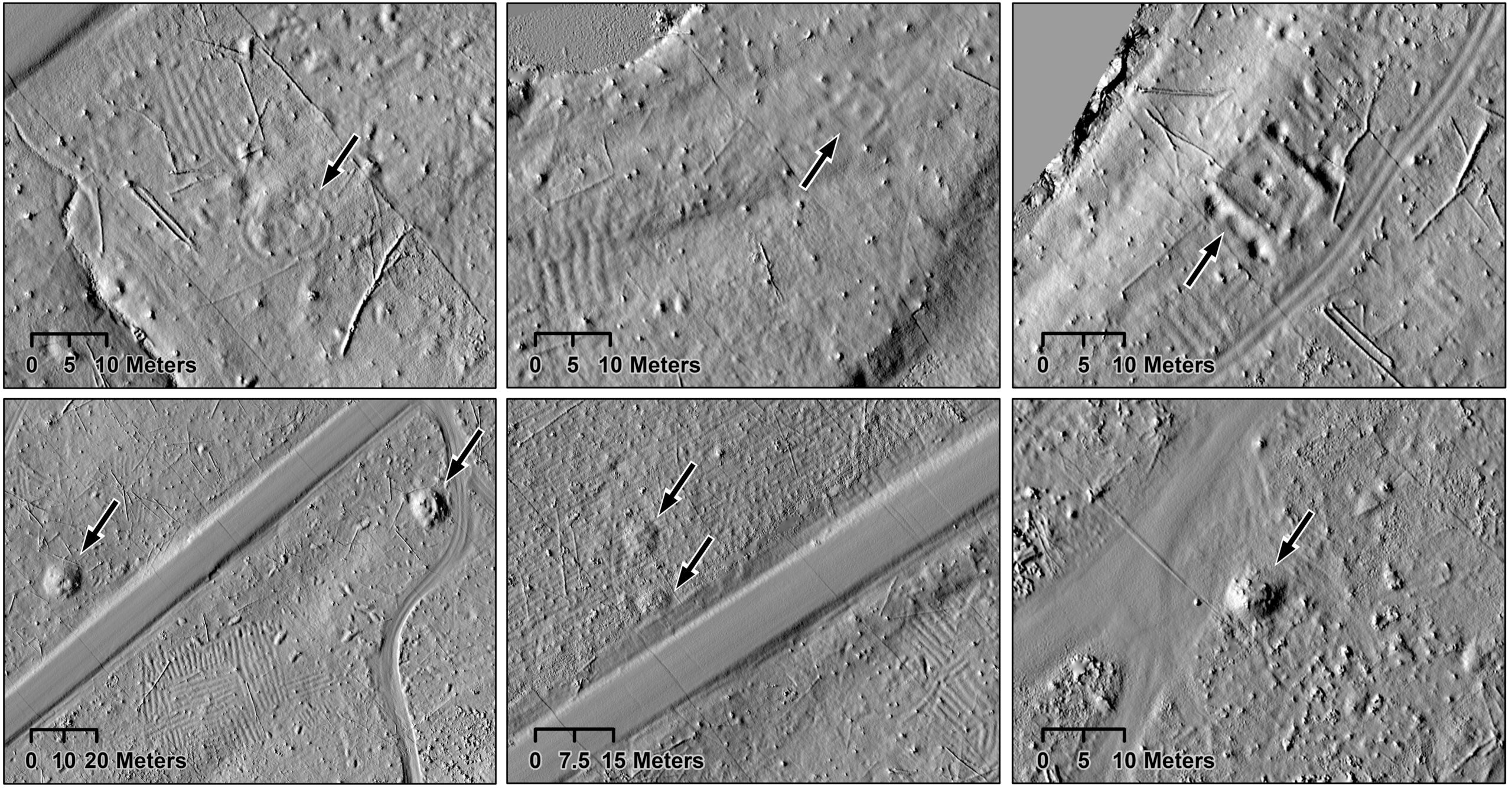

Identifying more archaeological features is an important step in the preservation process, so Grignon and Overstreet encouraged McLeester and her team to investigate the Sixty Islands site. In addition to their findings on the raised gardening beds, the Dartmouth team found features like burial mounds and a dance ring.

“I’m hoping that more features like mounds, ceremonial areas and burial grounds will be found so that we can preserve them as much as we can,” Grignon said.

New laser technology reveals hidden features

McLeester and her team used drone lidar technology, which involves flying a drone low to the ground and using pulses of light to map the topography of an area in great detail. Historically, lidar imaging has used planes, which can’t get as close to the ground and therefore aren’t able to pick up as much detail.

“This is some of the earliest data with drone lidar,” McLeester said. “I think with this new technology, we’re going to find more and more of these agricultural sites across North America in unlikely places.”

The drone lidar was able to find evidence of raised gardening beds over 95 hectares of land — 10 times bigger than what was previously mapped using traditional archaeological methods. The ridges are also denser than previously thought, and they extend beyond the survey area.

“There’s huge portions of the site, potentially, that are still not yet known,” McLeester said.

While raised gardening beds would have been common throughout the eastern United States during the precontact era, many of them were plowed or built over when the land was settled by Euro-Americans, especially on ideal farm land.

“They would have been the most common archeological feature, and now they are among the rarest,” McLeester said.

Beyond indicating a much larger scale of agriculture in precolonial Native American communities, the discovery at Sixty Islands is globally important.

“When we think about why communities undertake intensive agriculture, it’s typically because of things like population pressure and increasing hierarchies, neither of which we know of in the past for ancestral Menominee communities,” McLeester said. “It shows that you don’t need steep inequality to have intensive agriculture. There’s other ways that these systems come into being.”

The discovery has left McLeester and her team with even more questions than before — questions they’re investigating at the site.

“I’m really interested in how farming this far north was this successful. What are people adding to the soil to make the crops grow so successfully?” McLeester said. “I’m also wondering: Where is the village? We have tremendous, extensive agricultural features that could feed a lot of people. So I’m very curious where they were all living.”