Parents have been juggling work, child care, education and health issues pretty much forever. But when the pandemic hit, it laid bare just how precarious parenting arrangements were — especially for single parents, parents who can’t work from home, and the unemployed. Working mothers in particular lost jobs or were forced to quit to take care of children at home.

Journalist Alissa Quart, author of several books including “Squeezed: Why Our Families Can’t Afford America,” thinks this is one of those moments where parents need to refuse to go back to how bad it was before. In a story in Slate, she called for a parenting movement to emerge. There’s also momentum from the federal government for change, with the introduction of The American Families Plan, a suite of spending proposals for child care, child tax credits and paid family leave that the Biden administration calls “once-in-a-generation investments in our nation’s future.”

“To The Best Of Our Knowledge” producer Shannon Henry Kleiber worked with Quart and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project to talk with parents who are struggling but coming up with new solutions for the show “A Parenting Revolution.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

This is an abbreviated version of their conversation and have been edited for brevity and clarity.

Shannon Henry Kleiber: I wanted to start with being real about everything that’s going on in our lives today, and I was setting up for this recording and the dog was here and the kids were setting up their Zoom calls. And next door they started painting the house. There’s so much going on. The reality is, working from home and being a parent, you can’t separate them anymore.

Alissa Quart: Yeah, it’s a lot. It’s just a lot to try to have a professional life and to work full time. My husband and I probably work more than full time and have our daughter, doing every pick up, every drop off, trying not to use public transportation, so even things like that have become complicated.

I have a 9-year-old and everyone I knew has been having these kind of Rube Goldberg-like setups where they were working in the laundry room, working in a closet, having their kid have their virtual schooling near the bathroom and having their little kid on their lap while they’re doing phone meetings.

For women particularly, it was a real setback. It felt like a lot of the gains of the second and third wave of feminism and just women’s labor rights were being turned back, because it seemed to me — and the research bears this out — that women were bearing the brunt of this in households.

SHK: In some ways it’s such a universal problem. It’s cutting across race and class and geography. But as you say, it’s really striking feminism.

AQ: You can see a lot of the conventions of feminism and women’s independence that were attained, like (the idea that) you can have a life without a man in it and raise kids. You can have a blended family. All these liberatory personal choices that women were able to make in addition to working outside the home were now being set back.

If you’re a single mom, you literally have no one to rely on. Or if you’re a single woman without kids, you’re potentially completely isolated right now.

It’s been very strange from a feminist perspective, setting it back to this 19th century moment when the beginning of the child care system was created. It was a fragile system intended for the poorest, unfortunate women with no choice but to work, and who are being punished in some senses by a failed system in this country. And now it’s happening again.

SHK: What are parents doing who are really stuck? For the parents who need to be out of the house for work. The day care is closed and the school is virtual. What are they doing?

AQ: One of the people I reported on, she actually had her young adolescent son caring for her other two children who were seven and nine. And I think you’re seeing a lot of that. Someone was telling me about someone who works at their school going up to the Bronx from deep Brooklyn, dropping off her kid with her mother and then going back to school to teach in Brooklyn and then going back up to the Bronx, picking up her kid and then going back to Brooklyn (by train each leg of the trip is at least an hour). You’re seeing these absurdist lengths that people are going to just get any affordable, accessible day care that they find safe for their children.

“My son’s day care ended up closing before we were actually furloughed or sent home from my job, so I had to go a few weeks without pay. Eventually we did end up getting furloughed. But when they called me back to work, a lot of schools were shut down or you can’t go in, you can’t meet the teachers, you can’t go there because of COVID. And that’s a struggle … you’re giving your child to somebody. You put your child in somebody’s hands, so, just to not be able to meet everybody or even walk around the center to see anything, that was challenging. I did not find (anywhere) for him to go for a very long time — it’s already challenging, finding a day care that you feel comfortable with leaving your child for 40 plus hours a week.”

— Dasja Reed, a single mother of a two-year-old in New Orleans, Louisiana.

SHK: So much that comes from this pandemic pulls back these layers that we didn’t realize were there, or we knew were there and we were ignoring. We’re seeing the brokenness of child care, work, housing, the inequity. It would be so easy to get depressed about it. But one thing I really like about your work, Alissa, is that you talk about solutions. What can we do next?

AQ: One of the things that interests me is what other countries have done. Everyone points to Scandinavia. But even in Sweden, for instance, it was the 1960s and 1970s Swedish feminists that lobbied for the expansion of child care. So there was a mass movement. It wasn’t just, Oh, those Scandinavians with their good moral sense and their sense of social democracy,” it was women organized to put pressure.

And one of the things I’ve always been startled about, especially since I had a child — why are people not more organized and upset about this? Why isn’t there a parents lobby like there is for the elderly? Like I was thinking of AARP, it had a million dollars in total lobbying expenditures (on behalf of the elderly) in 2019. We need that for parents.

“I honestly believe that child care should be government-funded. If we put more energy in … (if) we just took into account that zero to four is really where we need to start, not in elementary once they get to kindergarten, I just truly believe that it would eliminate so many other issues that we have further down the line.”

— Dasja Reed, a single mother of a two-year-old in New Orleans, Louisiana.

SHK: I love the idea of the “parents revolution.” Are there ways people on the ground can create their own parents’ revolution?

AQ: I wrote some about this in my last book, and I’m writing a little bit about it in my new book because I think a lot of them are kind of bespoke things like co-parenting, where people are living together in the same house, even though they’re not biologically or romantically involved with each other. They’re sharing day care, pooling day care. I mean, everyone’s making fun of pods now as this “bougie” tendency. I prefer to call them “collaborative learning.”

The other thing is to organize and to send letters to fight for greater funds. I mean, the amount that’s needed when I reported this was just startling. The same amount was being given to Delta Airlines as was being given to help out with day care. (We need to treat) day care as part of the education system really, which would totally change how we thought about parents and children and our national responsibility to ordinary people.

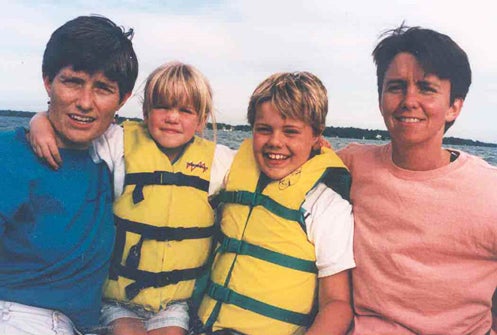

So Monica, I was very moved by her story. She’s a mom of three (with one on the way) in Lakeland, Florida, which had a very high rate of COVID-19 infections. And it had gotten so bad that the 7- and 9-year-old were at home with her 14-year-old, and they were not leaving the house sometimes. It wasn’t even a house — it was a motel.

Photo courtesy of Johanne Rahaman

“I have to worry about whether my kids are safe going to school. Are they wearing their masks correctly like I’m teaching them at home? Are the teachers properly following protocol and making sure our kids are being safe?”

— Monica Scott, mother of four in Lakeland, Florida

It all started when the Boys and Girls Club (where she lived) that once offered after school care, was shut due to the pandemic. So now she’s leaving at 7:30 a.m. in the morning for her job at McDonald’s. She’s paid $9.25 an hour and then she goes to sort boxes for Amazon at the airport at 1:30 p.m. and then works until 10 p.m.

SHK: And how is she handling it?

AQ: The thing that was kind of moving is (that) she’s an activist. She’s part of the Fight for 15 campaign to give $15 an hour for people like Monica who work at McDonald’s. And she said that was like the thing that made her happy, one of the only things that gave her hope right now, you know, she’s praying and hoping something good is going to happen was how she put it.

“It’s not easy parenting on these low wages. Making $15 an hour would definitely help provide child care and would also help us during these times of the pandemic. I worry about my kids all the time, you know. I want them to be safe and everything. I’m constantly praying for them. I’m praying for all the kids.”

— Monica Scott, mother of three with one on the way in Lakeland, Florida

And her life has been (going) from struggle to struggle — now it’s just a new level. Her kids would normally go to the ice cream truck and that would be this big joy in their lives. And they can’t even go without being accompanied by their older son, who’s not able to do sports anymore because he has to take care of his siblings. His whole adolescence is being kind of deformed and warped.

This is just one little story. But there’s probably millions of people whose kids and whose lives look like this right now.

“In the beginning, our full time day care provider closed for several months and my husband was also laid off. I was all of a sudden working from home, which was a little challenging. My son was not even one yet. He was pretty needy for me while I was here. And I was trying to get work done out of the house, and I was also breastfeeding. It definitely felt pretty hectic. We were also having to continue to pay for the child care that we weren’t using. So it became pretty challenging financially because child care in Vermont is about half as much as our mortgage.”

— Brittany Powell, mother of a two-year-old in rural Vermont

SHK: You do phrase it as an opportunity, I know there are some dark places too, but the opportunity and the necessity of doing something different right now is real, I think.

AQ: I’m more hopeful in some ways than I was before the pandemic started. Just because you’re seeing on television, on CNN, people are talking about people’s needs in a different kind of way because they’ve been forced to. And I think maybe one of the things is that people don’t really politicize parenting in this country. They individualize it.

And I think this is one of the obstacles. We need to de-individualize (the conversation), (since) every parent has the same problems.

“For some people, there are no real solutions. If you have a job where you can’t have your kid buzzing around while you plug away at a computer, you have to go to a job every day… what do you do if you quit your job and then you can’t pay your rent? How do you do that and not end up homeless?”

—Brittany Powell, mother of a two-year-old in rural Vermont

I think the inroads of people like (U.S. Sens.) Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren showed that there is the desire among a large number of people in this country to have a different kind of relationship to the state. To have a more interdependent sense of what we do for families, so not every family is siloed in their own difficulty. I feel like that’s part of what’s been exposed by this whole pandemic.