The hardest call Sharmain Harris made after being arrested was to his father.

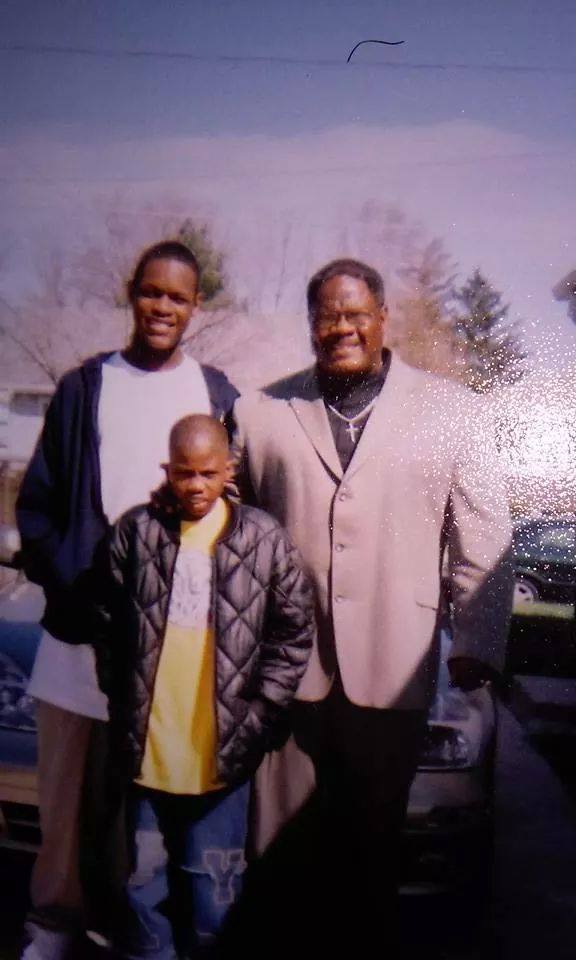

Just two years before going to jail, they drove to the University of Wisconsin-Stout together, so Harris could be the first in his family to attend college. After Harris walked into the dorm, his father sat in his car and wept with pride.

But in 2009 Harris was calling him for bail money. He felt ashamed.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“He and I both knew the odds of a young Black man from the ghetto making it out,” Harris wrote in his new memoir. “I’d gotten out but decided to drop out of college, and here I was headed to jail.”

In “Rising Above The Odds: My Journey From Pain and Prison to Power and Purpose,” Harris explores his life growing up in a Racine neighborhood plagued with gang violence — one that led him to start selling drugs at age 11 — and how family support led him to write his own narrative.

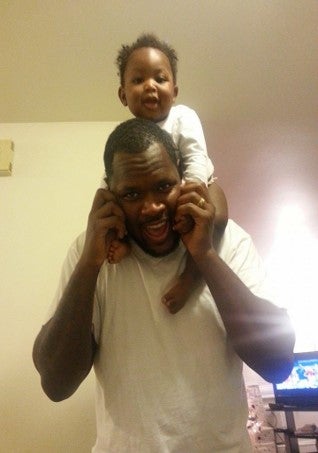

Today, Harris is a national professional speaker on father engagement, guiding dads in their relationship with their kids.

His experiences have led him to be an advocate for criminal justice reform. Although Gov. Tony Evers formally pardoned Harris of his crimes in 2022, the felon mark on his record can still prevent him from volunteering, finding a job or even housing.

“Prison is a terrible experience, but being free and bound at the same time is the worst kind of prison,” he wrote. “A societal prison that shows no mercy to the formerly incarcerated.”

Harris spoke with WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” about his new memoir.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Rob Ferrett: Tell us about your childhood.

Sharmain Harris: I grew up on Racine’s northside. It was tough in the 1980s and 1990s where a lot of things were happening societally.

Some of my early memories are police sirens and shootings. I remember a young lady being killed and smelling the crimson red blood on the concrete. It was just a tough experience and there wasn’t a whole lot of opportunity. You had to make the best of what you had.

RF: What was the appeal of selling drugs at such a young age?

SH: Well, the appeal was the fashion, the shoes, the clothes, the status. Growing up poor, you wear clothes from Goodwill and St. Vincent. And it’s tough because the people around you are so bought into these brands like Nike and Jordan. You feel like you have to measure up.

But, as I mentioned in the book, it wasn’t that I wanted to start selling drugs. One day I was going around the community asking for money for my birthday and the guy said, “Hey, stop asking for money. Here, take these two bags of crack cocaine and sell them. That’s how real men make money.”

RF: Encouraged by your father, you go to UW-Stout. It didn’t end up sticking. What ended up falling short there?

SH: When I left for college, I already thought I knew who I was. While there, I just kind of felt out of place. It was a predominately white institution and I didn’t really feel connected. And then on top of that, I didn’t understand how college worked. Nobody in my family before me went to college, so I didn’t understand financial aid and applying for this or that.

So I made the conscious decision to come back home but the subconscious part was going back to my friends and the people that I grew up with and going back to the streets.

RF: The most powerful moment in the book for me is when you’re in the Challenge Incarceration Program at prison. You’re in a group therapy situation and you made a decision to share some traumatic moments in your life.

One moment is when you went to visit your mom before being incarcerated. She was depressed and living by candlelight, sleeping in the dining room. There was no food in the house so you bought her a gyro cheeseburger. As she was eating it she told you, “Yum! Thank you, son, I was so hungry, I can feel the food going to my stomach.” You said you’d never forget those words.

SH: It was extremely therapeutic. And I’m one of those perceived tough guys, so part of me was like let’s get the most out of this program and maybe I can be a leader. So I went up and shared everything. I could barely get my words out because my tears were flowing on a piece of paper in front of me. But that started a ripple effect. Everybody else couldn’t believe it, and they started sharing their stories as well.

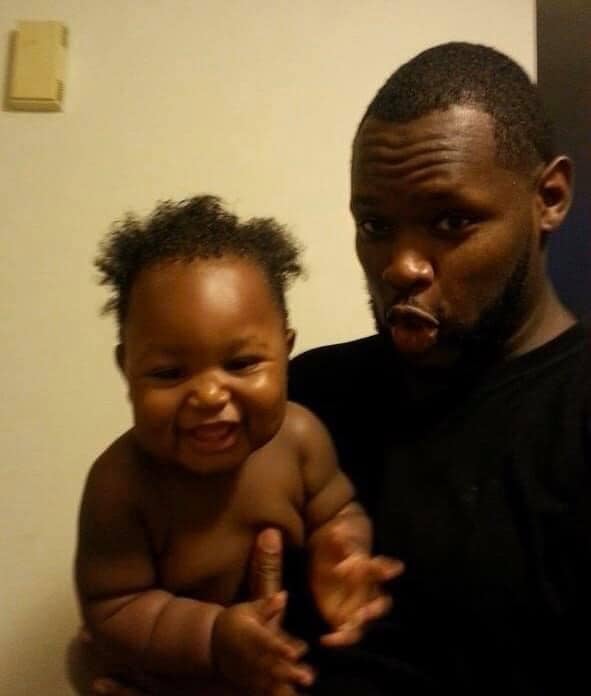

RF: You become a father and embrace this role as a leader, helping other dads become good fathers. What led you there?

SH: After getting out I went through these rough battles with employment because of my criminal record. During that entire time, my girlfriend, now my wife, was pregnant so I knew I had to change.

He was born, Jan. 2, 2014, and it was just eye opening.

I couldn’t see myself behaving the way I had. I refused to be somebody that’s not in my child’s life. I refused to have my son coming to visit me behind those walls and bars.

RF: A felony conviction has barriers. What kind of changes would you want to see?

SH: There’s a lot of conversation around second chances and feeling like people who have felony convictions deserve a second chance. But a lot of people don’t actually practice it.

You got great movements like “ban the box,” where employers don’t ask about criminal history, but that same concept can be applied to housing and other things.

RF: What would help a young kid getting into trouble today steer clear of incarceration?

SH: I’m big on fatherhood and people recognizing some of the obstacles put in our way. What would stop that kid would be if his father is around recognizing his importance.

If he’s not there, a community of strong men and women to support the kid. A community of support can help him dive into some of those deeper issues at an earlier age. You shouldn’t have to go to prison before you get a chance to be in therapy for the first time. So if that kid could have an early intervention it’ll make a world of a difference.