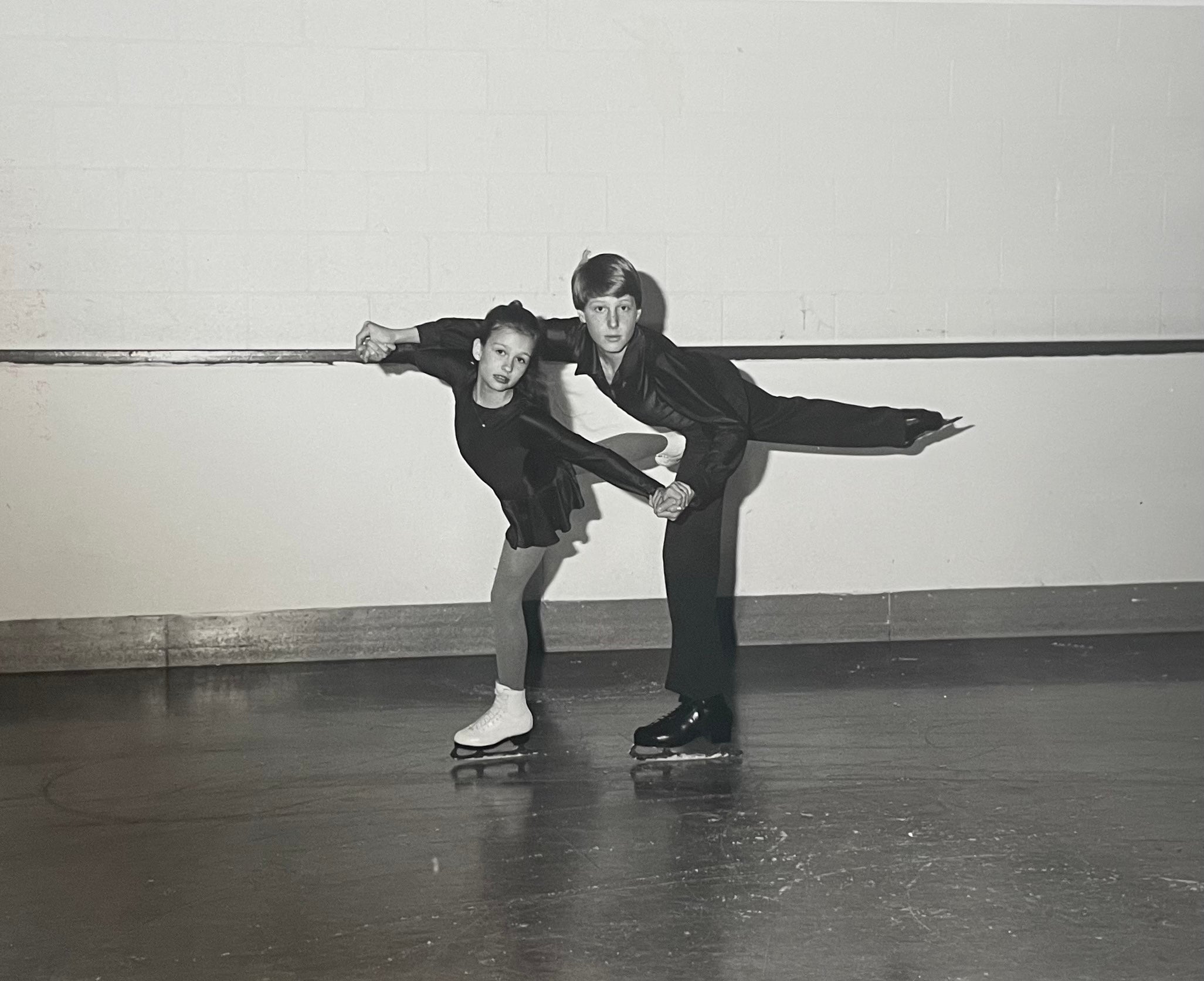

Growing up in Mount Horeb, competitive figure skating was a family affair for Jocelyn Jane Cox. Managed by their mother, Cox and her brother Brad rigorously competed side-by-side as a pair against elite athletes and future Olympians.

“I would say I was a 50-50 split of loving it and hating it,” Cox told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today. “And for (my mother), one child needed the other in order to complete his dream. I admired him enough that I did want to keep going. So I think she was in a tough spot.”

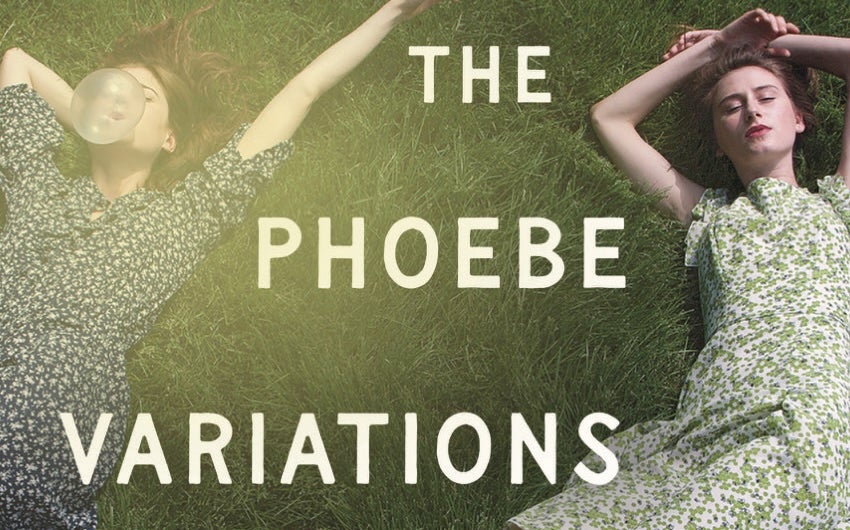

In her new memoir “Motion Dazzle,” Cox shares what it was like growing up as an elite athlete who, as a child, felt compelled to excel in her skating career for her family.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I see very clearly that (my mother) did, in her own way, give her life to our success in the sport,” Cox said. “I think ultimately that has made me who I am, and it did kind of lock me into the sport. I knew that quitting would be so disappointing to her and my brother.”

Cox writes the story in hindsight, beginning with the day of her son’s first birthday party — the same day of her mother’s death. And for the previous two years, Cox and her brother had come full circle, working as a caregiving team for their mother as she suffered with worsening dementia.

On “Wisconsin Today,” Cox shared more about what it was like to care for her mother while preparing to start her own family.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: Your mother was diagnosed with dementia when she was 75. How did you decide to include this aspect of your life in the memoir?

Jocelyn Jane Cox: My mother was diagnosed before I was pregnant, so I actually went through my pregnancy while caring for her during the beginning stages of her decline — which ended up being quite precipitous. The plot of my story that I follow is the day of my son’s first birthday party. It was a DIY affair, and it was zebra themed. On that day, my mother was in the hospital. By that point, there was significant dementia and also a lot of physical ailments happening, and she had been in the hospital many, many times. It got to the point where we couldn’t drop everything and drive the three hours down from New York to Delaware to be with her.

This is not really a spoiler because it’s baked into the book, but she did pass away that night. When I got the phone call, I said to myself, “This day will always include joy and pain for me. It will always be the day my son was born, and this will always be the day that I lost my mom. It will always be his birthday, and it will always be the day of her death.”

On some level, I saw how the zebra really embodied those opposite emotions and those opposite states of mind — not to mention these people were experiencing opposite trajectories in that he was in a state of ascension and she was in a state of decline.

KAK: Based on your experience, what kind of support do you think sandwich generation women need?

JJC: When we think of caregiving, I think a lot of times we think of caring for children. And just as every child is different, every elder is different, as well. So every parent is going to need different help. I think it’s very important for all parents to figure out how to find moments of self care and balance, and that’s doubly true when you’re also caring for your own parent. The reality is that you cannot be all things to all people.

I think for me, for example, hosting that birthday party, even though I was going through a very dark time, it was something that brought me a lot of joy. I wanted to have that fun DIY party because that fed me as a person. And my mother was an entertainer in that way. My mother was a tablescaper. She enjoyed putting on cute parties with themes, and I felt that I was continuing her tradition, but also saying, “Today I need to be a mother. I’m not going to be a daughter today, and I actually can’t do both.”

Has that given me some regret? Of course it has, because I was not there for my mother’s death. But I think also people in the sandwich generation need to provide some forgiveness for themselves and go easy on themselves because it is extremely difficult.

KAK: You’ve been writing now for years about your skating adventures, and at one point in the memoir, you say writing is like a form of therapy. How so?

JJC: I think other genres can be, as well, but there’s something about memoir; you are sifting through your memories, and you’re not just recounting them in a matter-of-fact, straightforward way. You are attempting to extract the meaning from these events that may be very complicated. And it’s not that you alight on some kind of answer, but you are able to find some peace with what happened. And I think that that process of writing this book allowed me to think about my mother’s life and connect with the person she was before she got dementia.

When we lose someone, and they have memory loss at the end of their lives, it gets very messy and very sad. My mother actually was opposite from how she was (before dementia). So the act of writing this memoir gave me the opportunity to connect with my mom and who she had been my whole life rather than focusing on those final, very difficult two years.