Before the era of data mining that’s now everywhere, University of California, Berkeley scientists in the 1960s began a first-of-its-kind longitudinal study to find out how personalities are formed — by observing and conducting experiments on a group of preschoolers.

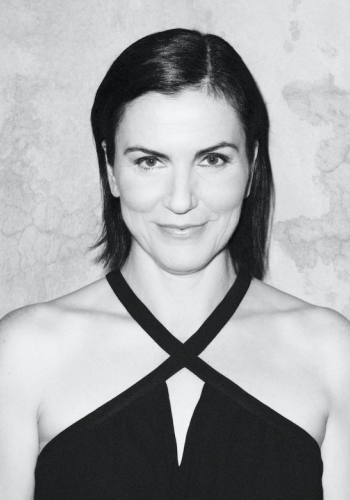

In her memoir, “Data Baby: My Life in a Psychological Experiment,” former test subject and journalist Susannah Breslin goes back in search of that data, hoping it will reveal something about her.

She talked with Angelo Bautista for “To the Best of Our Knowledge” about her experience as a child test subject and what personal data can ultimately say about ourselves.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Angelo Bautista: Tell me about your parents. What kind of parent turns their kid into a kind of guinea pig for these scientists?

Susannah Breslin: Well, my parents were first and foremost intellectuals. My dad was an English professor at UC-Berkeley, and my mother was an English professor at a smaller college in the East Bay. And so they really were interested in the life of the mind.

I think they saw themselves as sophisticated, educated people who were in one way or another gifted or special. So the idea that there was this special preschool for special kids who would be in this special study was fascinating to them. And I think it, to some degree, has served as a kind of status symbol. If you got your kid enrolled at the Child Studies Center, you are the child equivalent of having a BMW or something, a little elevated marker of who your kid might grow up to be.

AB: I was wondering if the researchers ever considered whether or not you, knowing that you would be part of the study, would affect the study at all? Kind of like an observer effect.

SB: Exactly. Yeah. I think in the mind of the researcher, they want to create a space where there’s a minimum observer effect as possible because that’s how they get the best data they can get. But the reality is that, as the observer effect dictates, it was impossible, certainly in my situation, for me not to be affected by the fact that I was being studied.

My parents were distant, especially my mother. She was a very sort of cool person who was not particularly interested in being a mother at a certain point. And so the study took on a kind of larger than life aspect in my psyche.

I’ve described it as the mother that I wanted that was always interested in me or always there for me, even when I wasn’t actually specifically being studied. It was a kind of shadow in my mind, giving me this sense that my life was meaningful. I had a purpose. I was part of something that was bigger than myself.

AB: So in a way the study that you were in became sort of this not necessarily parental figure, but someone that cared about you.

SB: Yeah. We were studying initially at the Child Study Center when we were in preschool, but after that we all went to different schools and grew up and moved to different places. But we would return for these assessments to Tolman Hall, which was where the psychology department was on the university campus. And we would be assessed in these testing rooms that had one way mirrors and it would be you and a researcher in this room.

And in a way, it was like a child’s dream, which is, here’s an adult who’s giving you its undivided attention. They wanted to know all about us. What our personality was like, what we liked, what we didn’t like, what was our relationship like with our parents, with our siblings. Had our parents gotten divorced or were they still married? Who did we want to be? Who did we think we might imagine being our romantic partner when we grew up? And that felt like love. So I really liked being studied.

“Maybe the study turned me into a voyeur, or maybe I was always going to be one. It’s hard to know the difference.”

Susannah Breslin

AB: You grew up to become a journalist and specifically a journalist covering sex and the sex entertainment industry. I can’t imagine you or the researchers studying you would have ever concluded that path for you. Why did you become a sex journalist?

SB: I don’t know if I have a simple answer to that question. I think in part, the study did shape my becoming a journalist in general. You could describe a researcher studying me in a way as being journalistic. They’re closely studying their subject. They’re creating a personality profile and they’re telling a story of a life or a person.

As I wrote the book, I did wonder why I became a sex journalist. Is there any way this has anything to do with being in the study? And the one common thread that I saw was that both things are heavily voyeuristic. There’s this peeking through these one-way mirrors and being spied on and poking into and peering into the most intimate aspects of somebody’s life.

The porn industry is what I’ve written the most about, and that is nothing but voyeurism. Maybe the study turned me into a voyeur, or maybe I was always going to be one. It’s hard to know the difference.

AB: It is hard to know. And you went on a quest to figure out what this study had done. So what compelled you to write about the study years later? What was going on in your life?

SB: In late 2011, I got married to a man I had met on a dating app and had known for nine days. We eloped in Vegas, and four days after that I found out I had breast cancer during the course of an annual mammogram. And I had a type of breast cancer that was more rare and aggressive.

I noticed that was of interest to the oncologists. One of the oncologists came in and said, “Hey, I have all these interns with me. Can we come in?” And they gathered around me and were talking about me and my case, and I was like, “God, this is like being studied again. This is like being a lab rat again.” And that brought back the study in my mind.

I moved with my then-husband to Florida, and my writing career was floundering. This was not how I thought my life would end up. I thought my life would be interesting. Is this where I was supposed to be — in an existential crisis?

And I thought, well, I wonder who the scientists thought I was going to grow up to be. And I thought there must be a file. The study must have kept all this data on me. I wonder what it would tell me about me.

And that propelled me as a journalist to go on this quest that would take me all the way back to Berkeley, where everything had started, in an attempt to figure out who they thought I would grow up to be.

AB: And did you think you would show up to Berkeley, they would just hand you your file and everything would make sense?

SB: You know, I think of myself as kind of cynical, but I think I’m actually also sort of strangely optimistic. And I think I really thought there would be this file. I’ll just open it and it’ll just tell me everything about who I am and everything will make sense.

That’s not quite what happened. That was part of a pattern in my life, where I was always looking outside of myself for something or someone else to tell me who I was. Wanting my parents to see me as this bright child, wanting the study to see me as exceptional. Wanting my then-husband to see me as a good wife. Being a journalist and wanting people to think I was so badass because I would go hang around the porn industry or whatever.

It was one more way I was trying to find my story outside of myself. And this book really forced me to tell my story for myself.

AB: So as you were digging, what were you able to find? What did you uncover about the study, about yourself?

SB: I didn’t get the answer that I thought I wanted, but all kinds of other things happened. I left my marriage. I moved back to Berkeley for a period of time to really immerse myself into that place that I had come from.

This is the question I cannot answer. I feel like this is the question I struggled to answer. I have a lot of trouble with memoirs. And I feel like people only value memoirs that deliver happy endings. And the promise of a memoir is that in the end, the main character discovers who she really is and accepts herself for who she really is. And loves herself and maybe goes like marries herself at Burning Man or whatever.

And I feel like reality is more complicated. I feel when I do these interviews that I’m supposed to say at the end of my journey, I discovered who I really was and now I’m enlightened and unburdened. It feels more complicated than that. I think that’s one of the things that I take away from it, is that the study was in many ways very beneficial to my life and saved me in some ways. So I’m very appreciative of it.

And it’s sort of funny how the study ended when we were 32. But here I am, 20 plus years after that. And in a way, I’m still involved in the study. Like I can’t let go of it.

“I thought originally I was looking for my data, but I was really looking for my story.”

Susannah Breslin

AB: You talk a lot about privacy in this book. This was a study done long before this era of data collecting and data mining that we have today. Did that ever come up for you, thinking about your private life, whether or not this was really invasive or crossed a line in any way?

SB: I thought a lot about privacy while working on the book. Privacy is just this antiquated notion. I have a kind of eye-rolling response to it. It no longer exists. When people talk about protecting their privacy, I’m a little bit like, are you aware that everyone just has their hands on your data at this point?

I don’t believe that any part of my life is private. We are aware that we are being surveilled, but we don’t quite seem to want to think about the consequences of that. I think that my experience being in the study was a canary in the coal mine version of what’s happening now, where kids’ lives are being quantified and shared from even before they’re born, when their mother posts an ultrasound online, and what effect that will have on them as adults — we don’t know yet. It is like another great experiment.

I was heavily impacted by being surveyed in this way. Children are not stupid. They know that they’re being observed, that their lives are being shared at a certain point. And I’m very interested to see what those kids are going to say about their lives when they become adults and start sharing what it was like to have the whole world watch them grow up online.

AB: If you did have access to every data point in your life, what would you do with it?

SB: It’s such a great question. One thing I learned during the process of researching this was there’s data and then there’s the story that you draw from it.

I thought originally I was looking for my data, but I was really looking for my story. So I think if I was presented with the mass of data connected to my life, I would just feel like I am not the sum total of a set of data points. What story can I draw from this data, which is already skewing things because now it’s becoming a subjective process?

It would be attractive, but also frightening because what if the sum total of the data of my life tells me that I am someone other than who I think I am or who I want to be? It’s a bit of a Pandora’s box, right? I don’t know if I would want to open it.