Managing a household can feel like a never-ending to-do list.

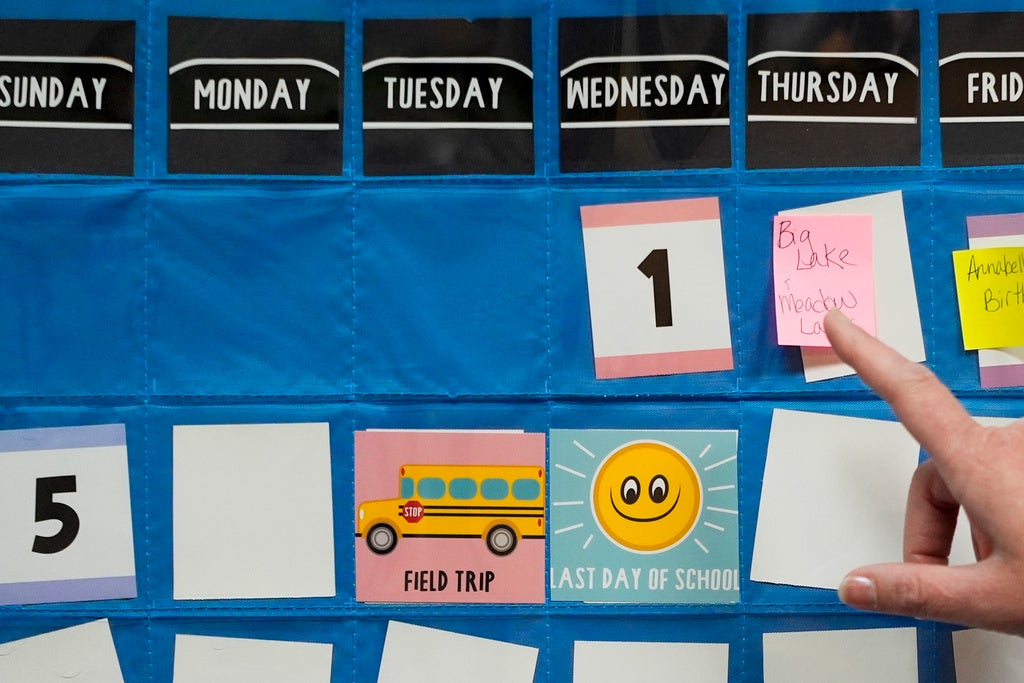

There are the visible tasks like cooking meals, doing the laundry, cleaning the bathroom or taking out the trash. But underneath all of that is a layer of invisible noticing and planning: “Are we running out of eggs? Or toilet paper? When does soccer sign-up open? Who is going to watch the dog while we go on vacation?”

This is what sociologist Allison Daminger, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, calls “cognitive labor”: anticipating issues, identifying options, making decisions and monitoring the results.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“It’s almost like a constant background job, as some of my interviewees described it, where you’re getting these frequent pings — things that you need to think about, things that you want to remember, issues to deal with — that you can’t really turn off in the way that you could perhaps silence a cell phone,” Daminger told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Over the past few years, Daminger has interviewed more than 170 people in an effort to better understand how cognitive labor is split up between partners running a household together. And the findings, she said, are no big surprise: It is mostly women who shoulder this load, even in heterosexual couples who aspire to equality, and despite the fact that the gender gap is narrowing for other kinds of household chores.

Daminger talked with “Wisconsin Today” about researching and writing her new book, “What’s on Her Mind: The Mental Workload of Family Life,” and what couples and policymakers can do to redistribute cognitive labor more equitably.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: In sociology research, how much housework each partner does is measured by time-use surveys. What does this time metric miss?

Allison Daminger: I think that there are a lot of great reasons to use time. This is something that we’re all familiar with — clocking in and out on a job — and we want to quantify the contributions we’re making. But what I’ve seen in my research is that so much of what it takes to run a modern household, to raise children and keep things going, happens in our heads. It would be very hard for me to follow someone around with a stopwatch and understand all of the many things that are going through their brain. They are looking ahead to: “What’s for dinner tonight? What are we doing this weekend? Oh, there’s this problem in our house that we should probably deal with.” And all of those things are really hard to translate into minutes and hours but are critical to the way that our homes keep going.

KAK: So you ask all of these couples to make a decision log of all the things that went through their head over the course of a day. What did you find?

AD: What I had couples do was track all the decisions they made, some of them on the small, minute things like (noticing that you’re low on shampoo), some of them much bigger: “Should we move? Where should we send our kid to camp this summer? How should we deal with a particular problem our child is having?” And I had them list them on these logs as a way to really get at who was thinking about what in the household. Not so much how they’re using their time, but how they are using their minds, and who’s in charge of remembering, noticing and kind of (doing) the project management of the household.

And in most of the different-gender couples, it was the woman who was really carrying the cognitive load in a majority of aspects of household life.

KAK: Did that surprise you in any way?

AD: I had a mentor say to me when I embarked on this research project that “You know, Allison, you’re going to have to do more than just tell us that women are doing this work.” I think it’s something that a lot of people intuitively recognize. So it wasn’t especially surprising. I think what was more surprising to me was how the couples that I interviewed made sense of these inequalities, because most of them told me that what they aspired to do was something close to 50/50, something that felt fair and equitable. And it was striking that they were so far from that ideal in so many cases.

KAK: How did they wrestle with that? How did they reconcile it?

AD: The most common thing that I heard people say was: “This is about our individual personalities.” So they would tell me, “My wife, she’s just so organized, and on top of things, she’s type A,” sometimes the word “control freak” came up. And they would say, “My husband, he’s just go-with-the-flow. He’s a laid-back guy. He kind of figures things out as he goes.” And so they’d say, “Look, I’m not going to put the laid-back guy in charge of managing our calendar. That’s just not a good fit for his personality.” But where I come in as a sociologist is to say: “Huh, it’s super interesting that all of these women happen to be type A, all of these men happen to be laid-back. What else might be happening here?”

KAK: You also talked with LGBTQ+ couples. What did you find there?

AD: I was a little surprised at first that imbalance or inequality was still the norm among the queer couples that I spoke with. The gaps between partners did tend to be smaller than they were between partners in heterosexual relationships, more like 60/40 than 80/20. The other thing that I found really interesting was that the queer couples didn’t tend to split the cognitive work into male-type tasks and female-type tasks. So what I mean by that is one partner wasn’t doing the finance and home maintenance while the other did the child care and shopping and cooking. It was much more of a mix-and-match situation.

I saw them really thinking about their circumstances and preferences and priorities, and customizing their arrangement. And they talked a lot more with each other about what they were doing. So it was much more of something that they felt like they had chosen for themselves and really fit them, in contrast to the heterosexual couples, who were much more likely to not have discussed these issues with each other.

KAK: So if you’re feeling overloaded, or you find that there is quite an imbalance in cognitive labor in your own household, what can you do?

AD: What I’ve found most helpful for myself is to really blame the system rather than my partner. Oftentimes, what I would see is couples who really felt that they were in conflict with each other, in kind of a zero-sum game. (However) you can take a step back and say, “There are a lot of social forces that steer different-gender couples in particular toward this kind of inequality.” We’ve talked about some of them today: It’s the social networks of moms that share information. It’s the expectations that society puts on women that are different from those put on men. And so I think the first step is to say, “Hey, we are up against some big obstacles here. But can we be a team, us against the world, rather than us against each other?” And for a lot of people, I think that makes the conversation more productive.

KAK: We’re in an age of intensive parenting. There is so much at stake. The economy is precarious. Every decision seems a little more weighty. How does that add to this cognitive labor load?

AD: The biggest thing is acknowledging the burden. One of the challenges that a lot of women that I’ve spoken with face is that they feel stressed, they feel anxious, they feel worried, and they struggle to name exactly why. And I think that having the language to say, not only are you doing these physical chores for your household — you’re driving your kids (to) various places, you’re cooking meals, you’re cleaning up — you are also juggling a lot of mental balls. You are thinking about so much. And so (it helps) if you can acknowledge that as important work that you’re doing on your household’s behalf.

There’s a lot of pressure on parents today, and I think that there are important conversations to be had about, how can we design policies and institutions that take some of that load off families? Redistribution within families is important, but I do think it’s important to acknowledge that if you’re feeling stressed and overwhelmed, it’s not necessarily because you have a bad partner or because you’re not doing a good job. There’s a lot.