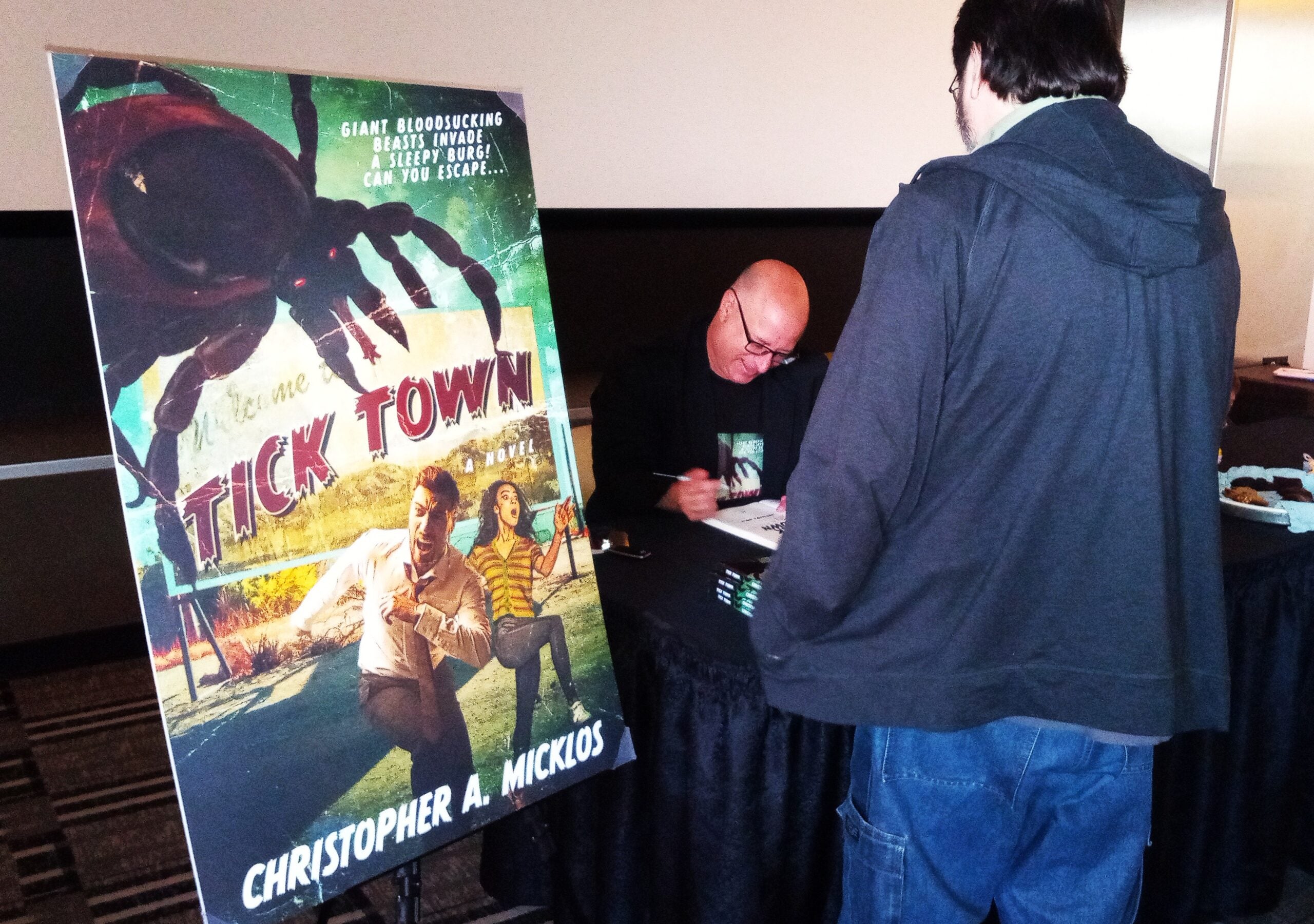

Look out! A band of mutant, monster-sized ticks have infiltrated a small Northwoods Wisconsin tourist town, and two reporters at a struggling local newspaper have to get to the bottom of the carnage.

That’s the setup of “Tick Town,” the debut horror novel from Christopher Micklos of Fond du Lac, a filmmaker, writer and a self-proclaimed lifelong horror junkie.

Micklos told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that he was inspired to write something in the style of pulpy horror paperbacks of the 1970s and ’80s, and ticks were the perfect Midwestern monster.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“If you actually ever look at a tick close up — and I looked at a lot of images of ticks close up — they’re pretty horrendously frightening creatures,” he said. “Their mouth parts are jagged and choppy, and they’ve got the long sucker that comes out and stabs into you. And the way they eat, it’s all pretty grotesque.”

For Micklos, it was a fun challenge to bring horror from the screen to the page. He said he especially wasn’t used to writing descriptions of gore and bloodshed, so he tried to take an exaggerated approach.

“I wanted to make it big. I wanted to make it broad. I wanted to make it splattery. And, you know, I think it’s fun,” he said. “I describe the book as PG-13 — there isn’t harsh language, but there is a lot of blood. But I think it’s more cartoonish, absurdist blood and gore.”

He joined “Wisconsin Today” to talk about why ticks are overdue for a creature feature, what it was like writing a Wisconsin-based horror novel and whether he thinks “Tick Town” could get a film adaptation.

The following interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: This book is about giant creatures in northern Wisconsin. Why ticks?

Christopher Micklos: I had set out to write something in the “creature feature” genre for my first novel, and I was very much inspired by a late ’70s pulp horror paperback called “Night of the Crabs,” about giant crabs run amok in the Welsh countryside. But crabs had been done so often, and spiders had been done so often, and scorpions and all that. I wanted to do something that was more relevant to Wisconsin, and what’s more relevant to Wisconsin than ticks?

Ticks are gross. They’re disgusting. They’re pretty horrendous creatures. And they’re responsible for a lot of disease and death. … So I thought it was a good subject that would be very ripe for horror.

KAK: You’re a filmmaker, you’re a podcaster, now a novelist. What inspired you to write “Tick Town” as a book rather than a screenplay?

CM: I’d never written a novel before, and I was very excited about trying to tackle the form. … I’ve thought about adapting it to a script, but … this would be outside my range to try and produce on a low budget. Giant marauding ticks probably would cost more than we usually spend on our movies.

I was so excited when I found that, boy, when you write a novel, you don’t have to worry about the budget and you don’t have to worry about the effects and all that kind of stuff that I worry about when I sit down and write a screenplay. And so it was a very liberating experience — basically anything that came to my imagination, I could write. And it ended up being a lot of fun.

KAK: One of my favorite characters is Emmaline Blackdeer, the upstart young cub reporter who really follows her gut and speaks out. Can you give us a little bit of an introduction to some of the main cast of characters that you created here?

CM: Emmaline is terrific. She’s a lot of fun, and she kind of represents the fresh, not-cynical member of the cast of “Tick Town.” And then her boss, Jackson Reed, who owns a small town newspaper that’s going under. Early on, I had envisioned some sort of metaphor for the gobbling up of local media by big mutant corporations, and there still may be a little of that in there. (Jackson) is more cynical. He’s trying to keep his paper alive, trying to keep a tradition alive.

Then there’s a cast of smaller characters that I tried to flesh out and tried to give some agency and pathos to. And then there’s a couple of cardboard cutouts — you know, these books from the ’70s and ’80s always had these mysterious villains, and they were often Nazis. So I made a vaguely Nazi character who kind of comes into the community and is tied to the group that’s responsible for the ticks.

KAK: You have these journalists who are struggling to keep the small local newspaper afloat, and you mention that the state Department of Natural Resources has funding cuts and isn’t able to get to the scene that quickly on these farms. Then you’ve got this shuttered factory, the Tomahawk Hollow Pesticides plant. How does horror as a genre grapple with real-world issues?

CM: As much as it’s fiction and as much as it’s kind of just goofy fun, you want some grounding that people can relate to and they can recognize. And I think a lot of those issues that you just described are things that people can recognize that are going on right here in Wisconsin.

Throughout the ages — going back to those early Universal movies to the big-bug nuclear horror movies of the ’50s and ’60s that were also an inspiration for this — (horror stories) have always reflected people’s anxieties, and they’ve always reflected the real-world concerns that people were grappling with.

I think when you’re trying to create something that’s going to affect people and stir emotions, you have to, in some instances, tap into things that actually do, other than insects and creatures and monsters. You start with the anxiety, and then you can kind of blow it up into full-blown horror.

KAK: What would it take to bring this to the big screen?

CM: My earliest reviews of “Tick Town” have commented on the fact that it’s written very cinematically, and I think that’s just the nature of how I am used to writing — I think in terms of pictures, and I think in terms of action. And so I think it’s completely ready for big-screen adaptation.

It would take a decent budget, though you can probably do it. Maybe a producer, like “The Giant Spider Invasion” (director) Bill Rebane here in Wisconsin — maybe he’ll see it and say, “Oh, this is something that would be good for a follow-up.”