Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau takes an official count of the nation’s population. While this might seem like a simple headcount, political scientist Philip Rocco says it is a major undertaking that requires years of preparation, robust funding and support from state and local governments.

Rocco, who teaches at Marquette University, has a new book out about the census, “Counting Like a State: How Intergovernmental Partnerships Shaped the 2020 US Census.” He told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that the population count has high stakes. The census determines how many congressional seats each state gets, along with the allocation of trillions of federal dollars.

“Even if there is a 1 percent undercount of the Wisconsin population, it means hundreds of millions of dollars in lost federal aid for programs like Medicaid,” Rocco said. “So there’s a real value in investing in outreach.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Right now, the Census Bureau is in flux under the Trump administration, which has eliminated 1,000 full-time equivalent jobs at the bureau and disbanded several major advisory committees. Rocco said that the middle of the decade is when preparation for the census normally ramps up, so there are growing concerns that the 2030 count could run into trouble.

“Because the census shapes the allocation of power and resources, politics really enters into the way that we count ourselves in a profound way,” he said.

Rocco joined “Wisconsin Today” to talk about takeaways from his research into the 2020 census and what is needed to prepare for 2030.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: In your book, you include a quote from a Greek economist that says, “Statistics is a combat sport.” How does that apply to the U.S. census?

Philip Rocco: If you think about the census, it is the primary way that we get the information that we use to allocate seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Electoral College, do redistricting at the state level and allocate trillions of dollars in federal and state aid around the country.

Thus it is not a stranger to political conflict because of the political power stakes involved in decisions about how we count people, who gets counted and what we try to do to correct for the fact that, on a fairly routine basis, numerous Americans are undercounted or systematically missed from the census.

KAK: And indeed, you dedicate the book to the uncounted. Who does the census miss?

PR: Historically, the census has undercounted people of color, Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, people in the Native American community, as well as people who are lower-income, people who are renters as opposed to owning a house. There are a lot of populations that are systematically undercounted by the census. And while the undercount has, generally speaking, gotten better decade after decade, 2020 was sort of a reversion of that trend. It was the highest undercount for a number of those populations since 1990.

KAK: From the outside looking in, we might think of the census as this straightforward, simple head count. Why is it way more complex than that?

PR: The census is one of the most difficult projects that the federal government conducts, and one of the main reasons why is convincing people that they should voluntarily fill out a census form on their own and return it to the federal government, especially in a climate where there’s a lot of distrust of the government. [It is] this thing that happens once every 10 years, when you compare it to other events in politics — elections are every two or four or six years. It can be very difficult to persuade people, even if they trust that their data are going to be kept confidential and private, that there is some return in the end for them taking the time out of their day and providing that form.

And if you think about the composition of the United States population: It’s growing. It’s changing where it is. … It’s just a very dynamic population, and a population whose relationship to the federal government isn’t one where there’s necessarily going to be a lot of trust. And so this thing that would seem really simple to do conceptually or on paper is, historically speaking, one of the hardest things that that we do.

KAK: You spend time in your book talking about how states are really relying on trusted messengers to go out, to educate and really activate the hardest-to-count populations to fill out the census. How have states done that and where do states fall short?

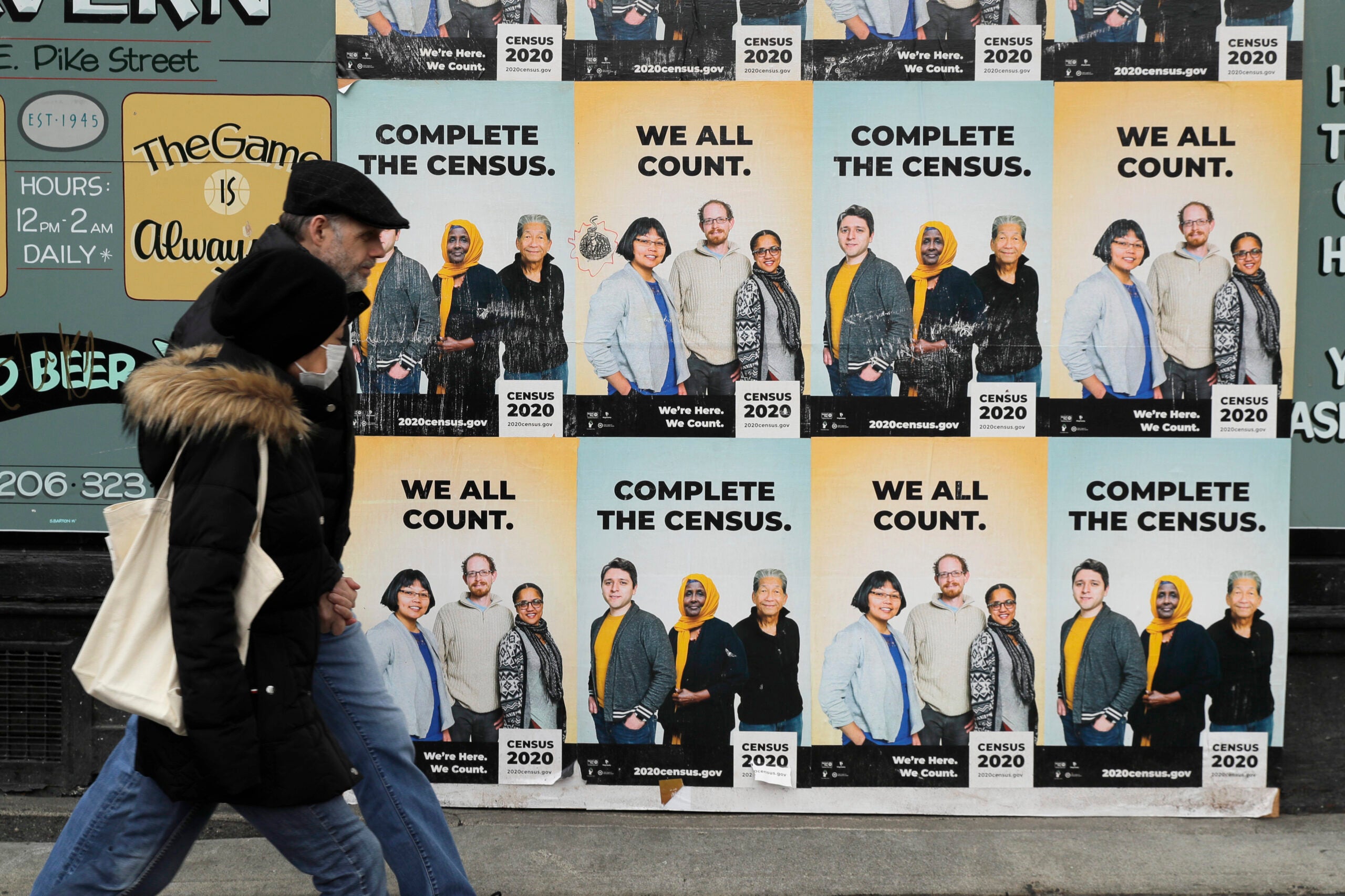

PR: For decades, the Census Bureau — when they started doing what’s known as the self-enumeration census or mail response — has known that it’s really important to reach people, not just through advertising, through commercials, through billboards and so forth, but through networks of trust — in other words, relying on officials and community leaders whom people already know to receive messages from those people about why it’s important and safe to fill out your census. … And so the Census Bureau really relies on other actors in society — and that could be nonprofit organizations, community-based organizations, states, tribes, counties, cities — to do a lot of that work.

In the 2020 census, state and local governments combined spent billions of dollars in coordinating their own outreach campaigns to reach people who are historically undercounted. California, for example, spent $187 million to create its own office of the census, which coordinated outreach campaigns in 10 regions of the state.

KAK: You found Wisconsin invested $0 for the 2020 census, whereas our neighbor Illinois invested over $30 million and New York City spent roughly $40 million on census outreach. Why was there this disparity in support in different parts of the country?

PR: Not every state, city, county is at the same risk of being undercounted. As a state, Wisconsin’s response rate to the census is actually fairly good, although there are pockets in the state where historically undercounted populations are far more numerous. Cities like Milwaukee would be one example, as well as some tribal areas in the state where the undercount is a bit higher.

But additionally, there is a partisan political tenor to these investment decisions. In some states, the politics of investing in the census were kind of politically poisoned by the Trump administration’s efforts to put a citizenship question on the census. … And then in states like Wisconsin, the census funding for outreach got caught up in a pretty predictable budget battle between a Democratic governor and a Republican state Legislature.

And finally, there are states, cities and counties where the level of resources that those governments have to expend on the census are very, very small. … The census can be seen by elected officials as a nice-to-have rather than a must-have, even if — and this is really important — even if there’s going to be a huge effect on federal funding or even representation from an undercount.

KAK: You talk about how ahead of any census, it’s the middle years that really determine the quality of the census — the designing and testing the questionnaires, preparing address lists, creating outreach plans. How is this looking now for the next census count in 2030?

PR: Census advocates are, in general, fairly concerned about the quality of the 2030 census for a variety of reasons. On the one hand, you have the Trump administration — there have been some signals that they will try to reintroduce a citizenship question on the 2030 questionnaire. And frankly, whether or not they do, they have taken some steps, including in recent weeks in Los Angeles and other cities, to create a climate of distrust that might have kind of the same effect on the census environment, the incentives of people to respond to the 2030 count, and so that’s pretty worrisome.

Additionally, there are some real questions about the adequacy of congressional funding for the 2030 census. … There are some real concerns about whether or not we’re doing what we need to do right now to ensure that the 2030 census is the best it can be.