It might be hard to believe in this age of artisan microbreweries, but Schlitz beer was once the most popular in the country.

For decades, the Milwaukee brewery battled for the top-selling beer spot with Budweiser.

“In the ‘50s, (Schlitz) had years where they were making billions in revenue. Billions with a ‘B,’” David Bourgeois, a writer and film producer, recently told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “For a family-run brewery — the Uihlein family ran it for decades — that obviously is a lot of money. It was just an economic juggernaut.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

That juggernaut came crashing down through a series of unforced errors — including a questionable marketing campaign, a rushed production system that led to a few skunky batches and an illegal marketing scandal.

Bourgeois and Michael Lander chronicled Schlitz’s downfall in an Esquire magazine article in July. The two have ambitions to turn the story into a feature movie. They explained to “Wisconsin Today” what happened to Schlitz and what the company once meant for Milwaukee and Wisconsin.

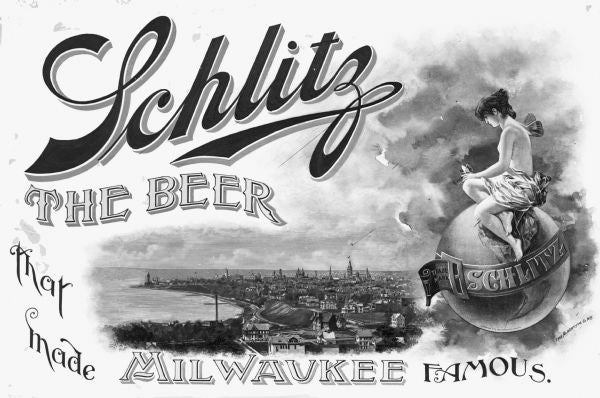

‘The beer that made Milwaukee famous’

Schlitz was one of several major breweries based in Milwaukee in the mid-20th century, along with Miller, Pabst and Blatz. Schlitz wore Milwaukee’s pride on its can, with the slogan: “The beer that made Milwaukee famous.”

All of the breweries helped make Milwaukee a thriving, working-class town, albeit one of the most segregated in the country.

“You could go to work at one of those breweries and have a really nice working-class life,” Lander said. “You could raise a family and have kids and a house and ink out a really nice middle-class life for yourself. It was a very attractive place to try to go and work.”

The two compare the city to Silicon Valley of the early 2000s.

A Schlitz scandal

The beer industry attracted Bob Martin to the city in 1952.

“Bob was one of those guys who, right out of college, was like, ‘Hell yeah, I’m going to work at the second largest brewery in the world, a multi-billion dollar company,’” Lander said. “It was a hotbed place to work. It was super cool. There was even a television show in the ‘70s called ‘Laverne & Shirley’ that took place in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and they worked in a brewery called Shotz.”

Martin took a job in the company’s marketing department, and he eventually rose to senior vice president. As the Esquire article documents, Martin and others in the marketing department played fast and loose with the rules, using money in big and small ways to ensure that Schlitz taps were prominent around the country. The accounting schemes eventually led to hundreds of indictments from the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Some of the things that Bob Martin was spearheading were kind of comical, very small infractions such as walking into a bar and saying, ‘Oh, looks like you could use a new floor. Well, we can take care of that as long as you ensure that … Schlitz is in five of the six taps,” Bourgeois said. “Which is small potatoes.”

But Martin had bigger schemes in mind, as well. He helped orchestrate a takeover of the taps at O’Hare Airport in Chicago in 1976 — then the largest draft account in the country — when a strike at Budweiser left the airport scrambling for beer.

He also helped finish construction of the Houston Astrodome, the world’s first domed sports stadium. The developer was short on cash to finish construction, so Martin advanced him $225,000 (worth about $2.3 million in today’s dollars) of Schlitz money in exchange for exclusive rights to sell beer there.

“There were ways that Schlitz would do end runs around the law to ensure that Schlitz got prominent placement,” Lander said. “They ran a lot of money through advertising agencies that never did any advertising. It was all a way to get money back to venues, to bars, to ballparks to train stations, train hubs, you name it. And they would have to come up with fairly inventive ways of moving money around.”

Schlitz eventually settled the case with the SEC in 1978. Martin always denied wrongdoing. Lander said the story underscores the importance of regulations to help ensure a level playing field.

“We used to put very simple rules in place to control the monopolizing of any industry,” Lander said. “I believe Bob thought that these little rules are silly, not realizing that those little rules were keeping small businesses alive, helping mom and pop businesses survive.”

‘Drink Schlitz or I’ll Kill You’ ad campaign

Schlitz made other questionable moves that led to its demise. One was an ad campaign featuring a narrator offering to replace Schlitz with a different beer for various macho men — a boxer, construction workers and an outdoors man — who all threaten bodily injury or worse to the narrator for trying to take away their “gusto.”

“It was so disastrously bad that this ad campaign is taught in some marketing classes on exactly how not to market a product. It’s kind of head scratching,” Bourgeois said. “In essence, (the ads) drove people away from the beer because they were a little creepy and frightening. Certainly, in retrospect, they’re funny. But at the time, people were like, ‘What?’”

Schlitz fired Martin in the late ‘70s. He in turn won a libel suit against the company.

In 1982, Stroh Brewery bought Schlitz for $500 million. It was later sold two more times, and the original formula for it was believed lost. In 2008, Pabst — which had taken ownership of Schlitz — recovered the original formula and began making it again.

Bourgeois and Lander hope to tell the story of Martin and Schlitz’s downfall in a movie or TV show.

“I’m a screenwriter. I’m a writer-director, so I always sort of look at everything through that lens,” Lander said. “And when (Bourgeois) brought the story to me, I was like, ‘This looks like the cast of “Anchorman” starring in “Goodfellas” in Milwaukee in the late 1970s — with a lot of heart. There’s a lot going on in the background.”