When St. Marcus Lutheran Church was founded in 1875, the surrounding city of Milwaukee had gas-lit streets with horse-drawn carriages and wooden sidewalks.

The church and the city have come a long way in 150 years, and its longtime pastor documented that history in a new e-book and a series of talks this month at the church.

Pastor Mark Jeske’s book, “The History of St. Marcus” provides a window into how Milwaukee has grown and the role that religious institutions have played in its neighborhoods.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

He joined WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” to share what he learned and what lessons can apply to the challenges facing churches today.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: What was Milwaukee like in 1875 when St. Marcus Church was first formed?

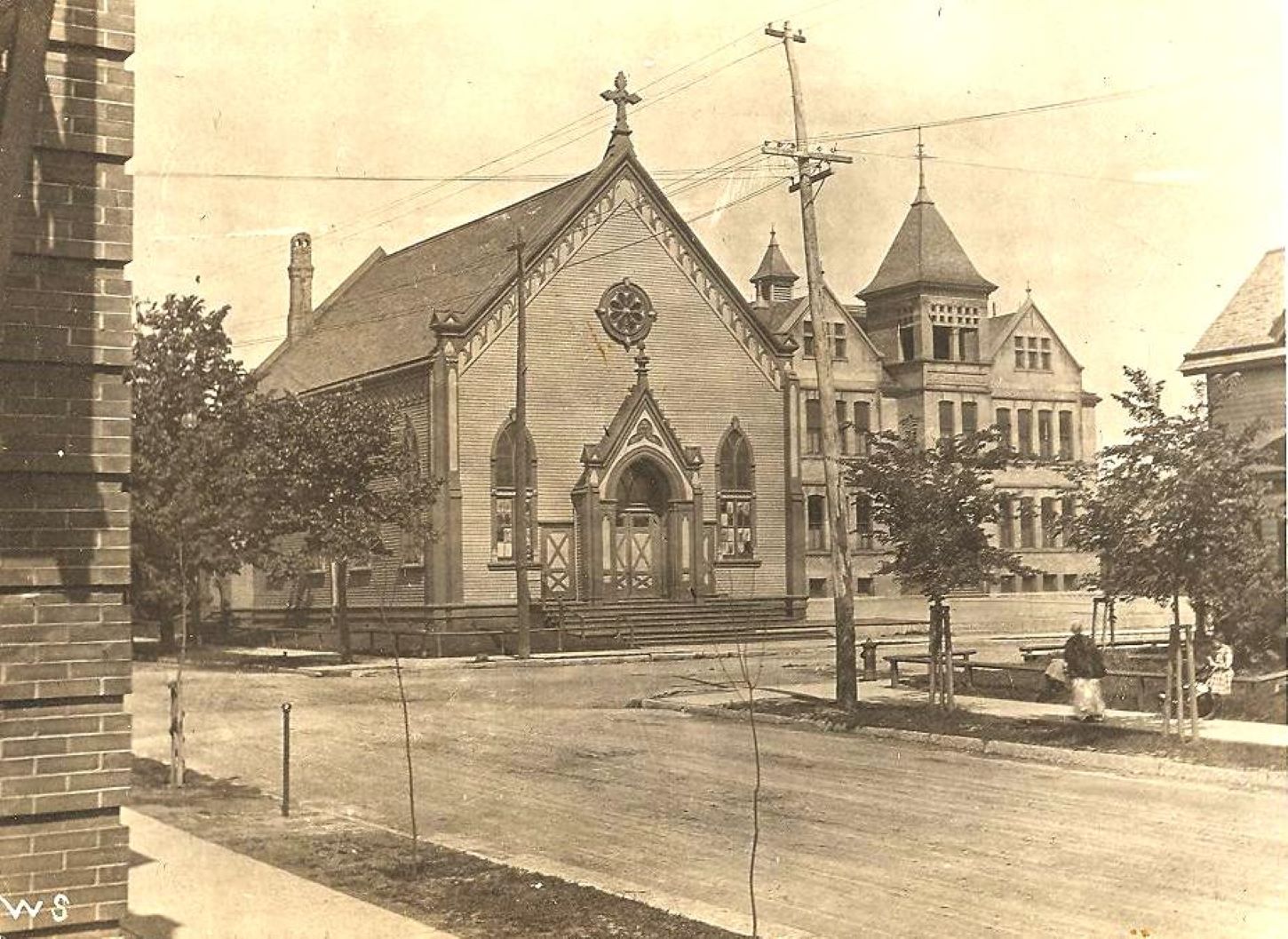

Mark Jeske: The congregation began as a one-room schoolhouse. We were a daughter school that branched out from St. John’s Lutheran Church at that time, located on 4th and Highland, so in the Deer District, about a half a block away from … the Fiserv Forum. In 1875, [St. Marcus’] one-room schoolhouse was on the very edge of town. There was nothing north and east of that one house on the block. Obviously, it’s changed extraordinarily, to the point where today it’s considered one of the most densely populated inner-city neighborhoods.

KAK: What did you learn while documenting these 150 years of history of the church that you didn’t already know from over 40 years of service there?

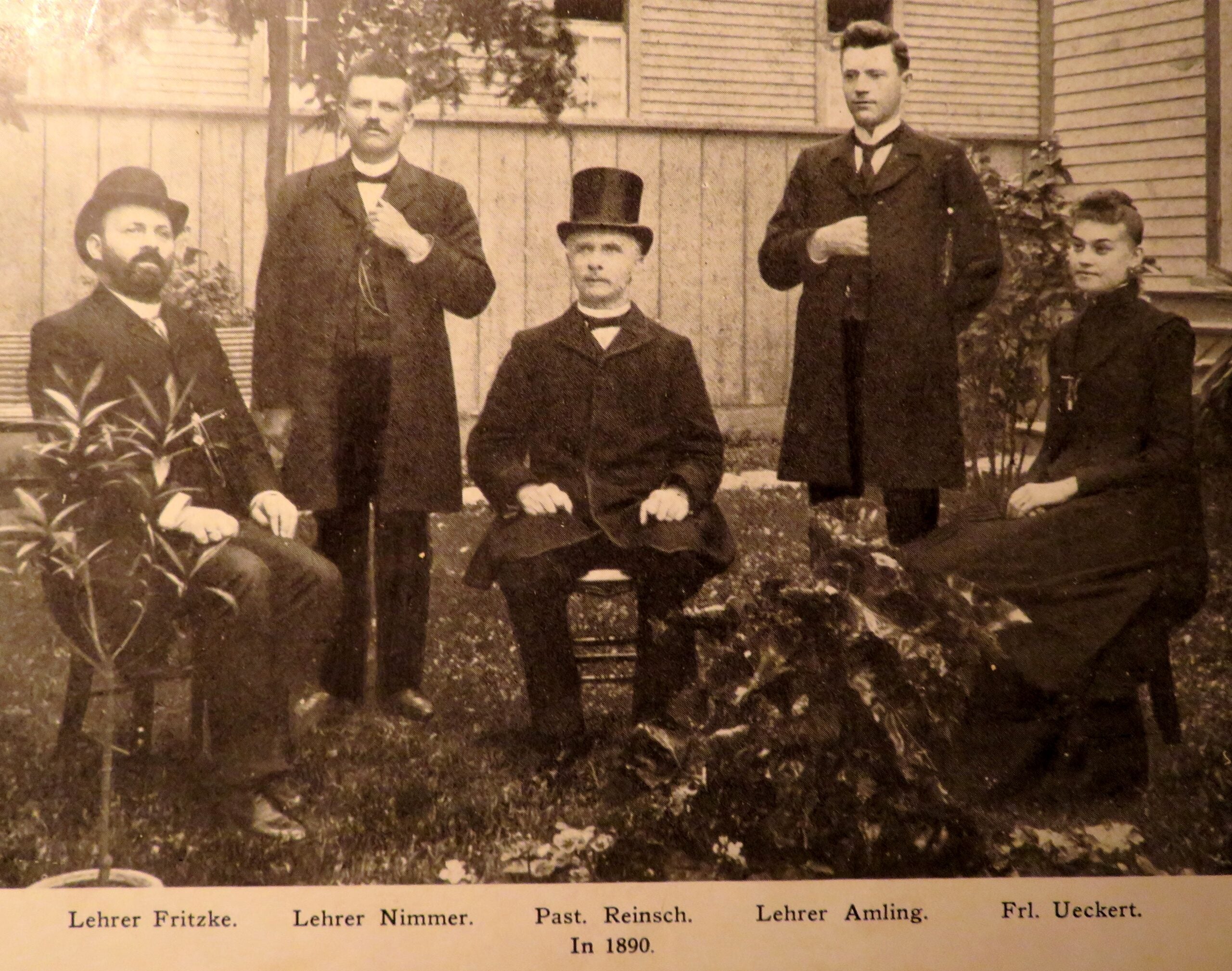

MJ: I would say, how bad things had gotten after World War II. That part of Milwaukee went through a dramatic demographic change during the war, and the neighborhood that St. Marcus was in very quickly went from almost completely white to almost completely Black. That was a bewildering social change. Whites did not know if they could trust Black folks. Black folks most certainly did not know if they could trust white folks.

That for St. Marcus changed in the middle ‘50s. We had our own Montgomery situation in 1955, and that’s when St. Marcus became multicultural. The pastor at that time was absolutely determined that he was going to integrate the congregation.

KAK: You were ordained in 1980 when the church was dealing with big membership declines and the school faced enrollment declines. How did you meet those challenges?

MJ: Well, first of all, I was too young and dumb to be as worried as I should have been. We were much closer to dissolving than I realized at the time. I was naive enough to think, if you just work really hard and pray like crazy and treat people kindly and with love, that we would start growing again. We didn’t die right away when I got there, but really the numbers of people in worship services did not turn around until I had been there six or seven years, and then it began to grow again. So the Lord had some real chastening and humbling to do first, so that I wouldn’t think I was a genius. I had to work a lot harder and do a lot of learning and listening first.

KAK: What are some lessons learned back then that can be applied today, as we see churches and schools grappling with similar declines now?

MJ: Learning to enjoy a relationship with somebody who is not like you is not simple or organic behavior. It’s always learned behavior. You have to learn how to do that. You have to want to do that. You have to choose to enjoy doing that. The reason that many congregations today are still folding is that their new neighbors are not like them and their demographic tradition.

It all comes down to two things: Do you know what you need to do to embrace someone not like you, and do you want to do it? Those two things are the only two questions that interest me. If you don’t know what to do, that’s ignorance, and ignorance is curable with information and inspiration. If you really don’t want to do it, I think God in heaven just says, “Well, alright, I’ll find someone else to do it for me, and I’ll just let your organization die.” And he seems very at peace with doing that, if you do not wish to connect with people not like you.

I think that’s the secret sauce of our congregation, that by committing to doing that, we committed to make ourselves uncomfortable 10 or 20 percent of the time. That’s when you learn things — when you’re uncomfortable.