Whenever you do a Google search or send a Gmail, an office in Madison, Wisconsin has a supporting role.

The office, in a nondescript commercial building overlooking Wisconsin’s Capitol, is more than 2,000 miles from Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. But it’s home to over 100 engineers at work on designing hardware and software for the tech giant’s data centers.

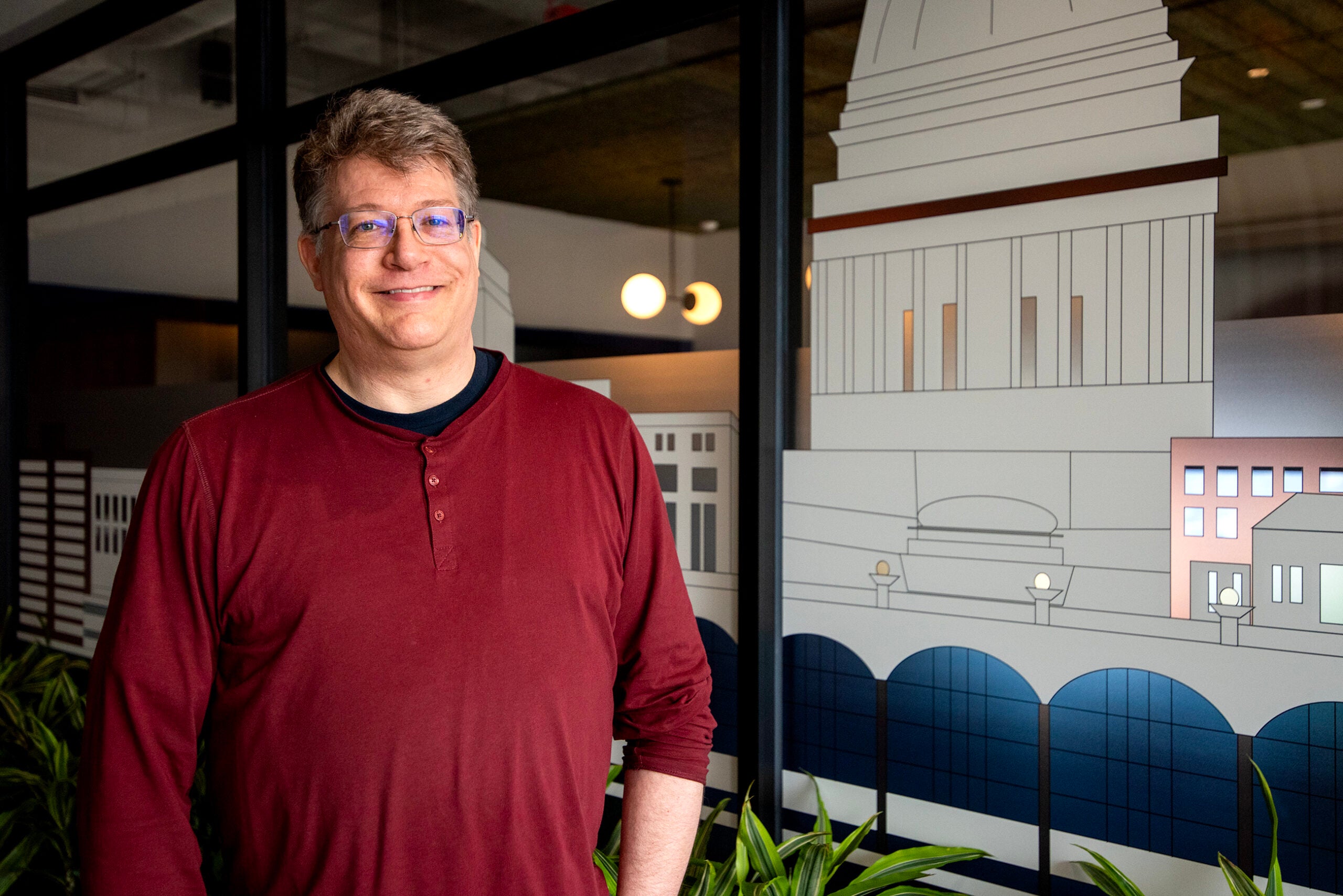

“Every time my son uploads something to the classroom or my daughter’s concert for elementary school is live streamed on YouTube … there’s work being done in Madison that’s some piece of supporting all of this,” said Milo Martin, the current engineering director and site lead of the Google Madison office.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The small office grew in Wisconsin to capture talent from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2007, a former UW-Madison professor and team pitched it to Google, hoping to help the multinational technology company develop its data centers while staying close to home. Decades later, the office continues to specialize in software and hardware for data centers.

Google Madison — one of over 70 offices the company operates worldwide outside its corporate headquarters — has continued to attract graduates from UW-Madison, including Martin, who earned his Ph.D. there in 2003. The company has offices in tech hubs across the nation, many with major universities nearby.

Martin returned to Wisconsin to work at Google after holding a faculty position at the University of Pennsylvania for 10 years.

“A bunch of people I knew from grad school were some of the first five or 10 employees,” he said.

Now, the office not only attracts employees from UW and other Midwest campuses, but also across the world, Martin said.

The ‘backbone’ chip

Wisconsin Google engineers have touched international projects. Perhaps most notably, the office laid the blueprint for a chip that helps power Google’s AI.

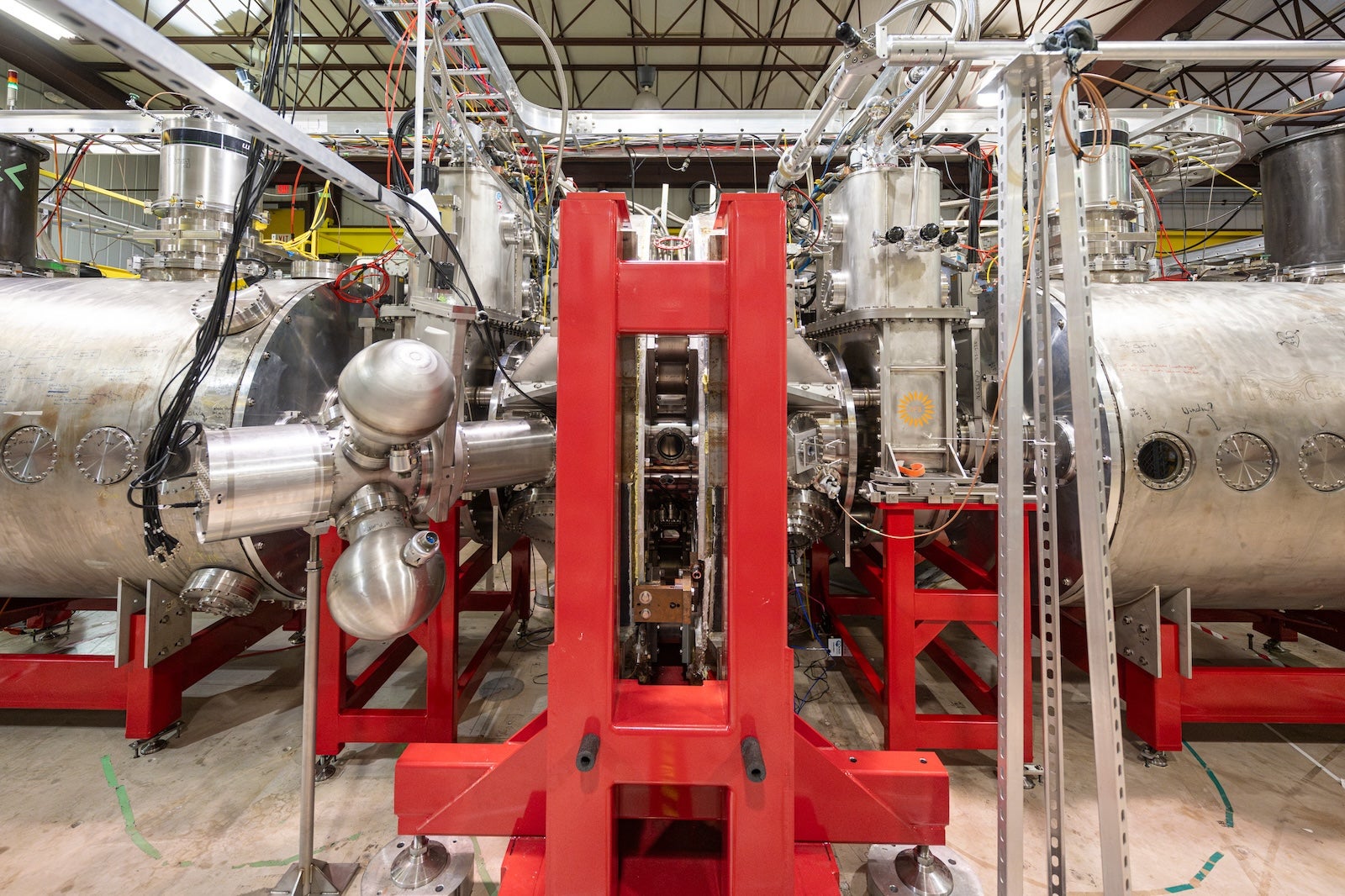

Over a decade ago, the Madison office began laying the framework for Google’s chip, a tensor processing unit, or TPU. At the time, the company’s demand for computational power was growing faster than its infrastructure.

AI models rely on lots of mathematical computations being done in a certain way over and over, Martin said.

“By building a custom piece of silicon, a chip, that’s really good at doing those things, it can be not just twice as good, but 10 times, 100 times, in terms of being more energy efficient or being faster at doing those computations,” he said.

Today, TPUs are the “backbone” for nearly all Google’s products, a recent company article said.

“It started here,” Martin said. “And then, of course, it’s grown to be many offices and lots of people working on it, but some of the core pathfinding was done here.”

The Madison office also specializes in “high-speed networking,” for example, helping computers in data centers communicate. High-speed networking helps compute things faster and with less latency, Martin said.

“It’s a lot closer, it’s smaller, has a different set of problems, and so we’ve done a lot of work to tailor Google’s networking infrastructure and stack to be super high throughput, super low latency and reliable,” Martin said. “This office has had a lot of input into those things, both for our internal workloads and for cloud computing.”

His office has also collaborated with other Google teams on projects such as a Nobel Prize-winning artificial intelligence model called AlphaFold used to predict protein structures to help scientists understand things like antibiotic resistance.

“Engineers from the Google Madison office are proud to have played a small but critical role in providing a software storage infrastructure that allowed fast access to genetic sequences during the training of the AlphaFold model,” Martin said.

Strong university ties

Google Madison benefits from having a top notch computer science program nearby, Martin said. For example, he joined other Google representatives in November at a “pitch competition” at UW-Madison, where students proposed ways the company’s data centers could reduce their environmental footprint.

The benefit goes both ways, said event organizer David Ertl. He’s the executive director of UW-Madison’s N+1 Institute, a division in the university’s School of Computer, Data & Information Sciences formed last year that partners with companies like Google Madison to bring students industry experience.

UW-Madison computer science graduates are recruited at both Google Madison and Google in general, Ertl said. Its graduates are historically good at systems technologies that companies want.

“I think it is a two-way street,” Ertl said. “It helps Google to recruit our excellent students, but at the same time, it helps us attract students, knowing that Google’s actively recruiting here on campus.”

He said having a Google office nearby helps the university maintain ties to the company. Google Madison staff also help mentor UW-Madison computer science students in capstone courses.

“They work on a project scoped specifically by Google,” Ertl said. “That is an excellent way for our students to get experiential learning opportunities.”

The university has recently been threatened with federal funding cuts, which the N+1 Institute has avoided because it’s mostly funded by industry partnerships. But elsewhere, there’s longstanding practice of the government helping fund computer science research.

“There’s lots of different ways in which the U.S. government has supported research and development in computing,” Martin said. “Google, in general, was founded by Ph.D. researchers that were doing a Ph.D. program. I assume they were federally funded at the time.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.