Growing up in Michigan, Barbara Boustead was afraid of thunderstorms. She was also a voracious reader, so her mother had the idea to take young Barb to the library to read up on the science behind weather to calm her anxiety.

“By learning about it, I was able to overcome fear and turn it into curiosity,” Boustead told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “That’s the passion that my family fed as they took me to the library and got me books on the weather. (That) helped me explore weather safety and weather preparedness and just what weather is and how it’s made.”

By the time she was in first grade, Boustead had read all the books about weather from both the children’s and the adult nonfiction sections of the library. She told her mother that she wanted to be a meteorologist when she grew up — a goal she is now living out as a professional meteorologist and climatologist.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Around the same time as her weather reading blitz, Boustead’s mother handed her a copy of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House on the Prairie.” Soon after, she read “Little House in the Big Woods,” a children’s book Wilder wrote about her earliest years, when her family lived near Pepin, Wisconsin.

“I think I had the weather bug and the Laura Ingalls Wilder bug both bite me at about the same time,” Boustead said.

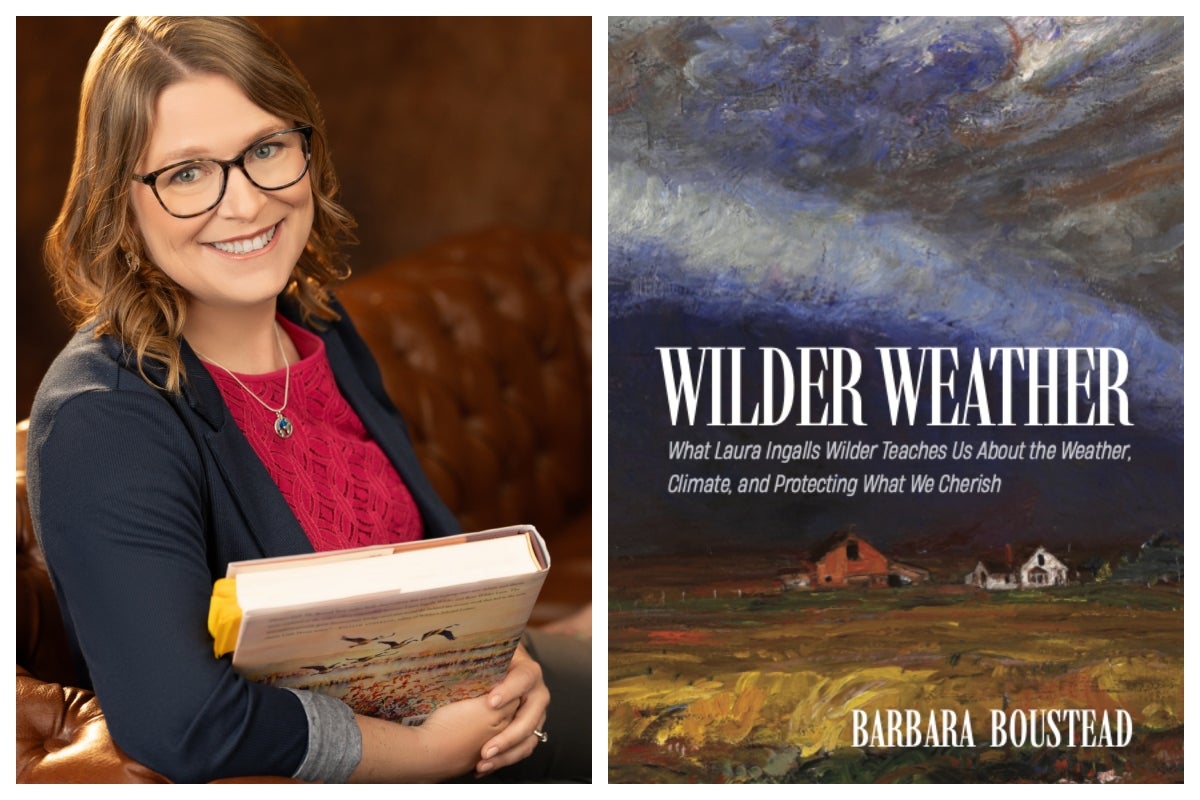

For the past two decades, Boustead has been combining her love of and expertise in both the weather and the “Little House” series by sharing her research online and attending LauraPalooza, the official conference for Laura Ingalls Wilder scholars.

Now, Boustead is out with a new book that collects her findings from over the years, “Wilder Weather: What Laura Ingalls Wilder Teaches Us About the Weather, Climate, and Protecting What We Cherish.”

Boustead joined “Wisconsin Today” to talk about the science behind Wilder’s vivid — and sometimes harrowing — weather tales and how storytelling about the weather can paint an important picture for scientists and future generations trying to understand our experience of the changing climate.

The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Kate Archer Kent: You write that in Wilder’s books, weather isn’t just part of the scenery — it’s a character unto itself, and even an antagonistic one. What makes weather so prominent in the “Little House” series?

Barbara Boustead: I believe that as Laura was growing up and her family was moving around, they were so vulnerable to the weather conditions around them and to the climatology around them that they became more tuned to observe and pay attention to what was happening in their air and water and landscape. And then as Laura grew, because she had paid such close attention to those weather stories, the weather information was really imprinted in her memory.

KAK: And this piques your interest as a meteorologist because you’re taking this data-driven documentation from the 1800s and layering that onto Wilder’s observations. What do you find out from that?

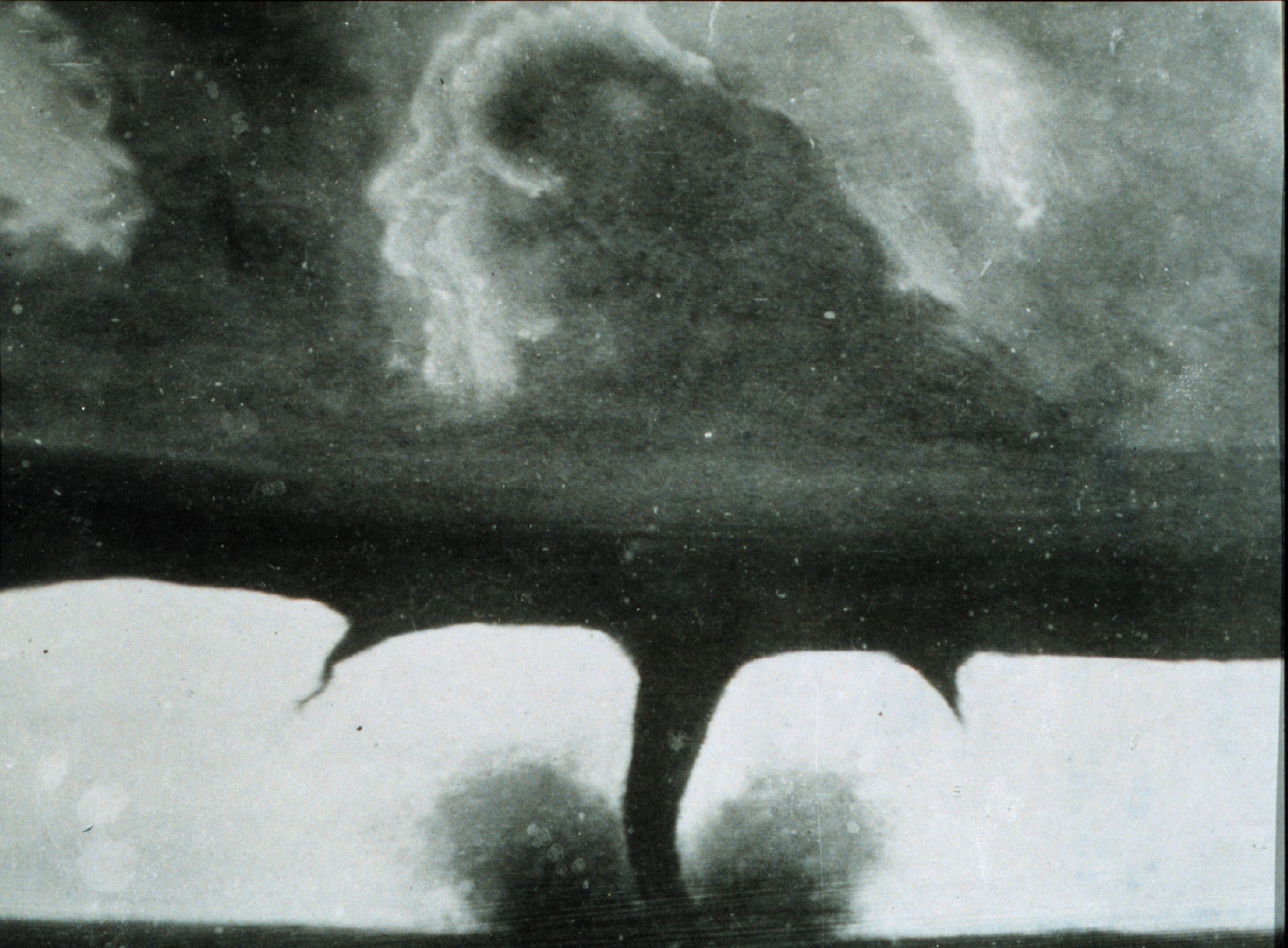

BB: When we have our weather observations, our record of the past, that gives us what I would say is a skeleton, like you’re digging up dinosaur bones. And with those bones, you can see the shape of the dinosaur. You can pretty much tell if it ate meat or plants, maybe a little bit about how it lived, but you don’t know what color it was or what sounds it made or what its skin texture felt like.

I think when you combine the weather data with stories like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s, you add that depth of information, that flesh to the bones, if you will. So you do get the sound and the feel of what that weather was like — not just the data, but what it was like to really experience it in that time and place.

KAK: So Wilder was born in Wisconsin and wrote about her family’s time near Pepin in “Little House in the Big Woods.” What were some of her observations of the changing landscapes in Wisconsin?

BB: Laura was fairly young when she was in the Big Woods. She lived there twice, once as a baby to young toddler age, and then again around the age of 3 to 4. And with her memories, she does have some recollections of things like maple syrup-making during her childhood with her grandparents, and I think she reflected on that as an adult, not so much in what it was like to make syrup and have a dance because there was a “sugar snow” that made the maple syrup run longer, but that the landscapes were changing. People were cutting down the trees, and things looked different.

She wrote about it in her adult years in an article in the Missouri Ruralist, which was a paper in which she had a column where she reflected on the great woods of Wisconsin and how they were changing. And those changes had an impact on what it was like to live in Wisconsin, which, for her time, was quite a bit ahead of itself — that she was paying close attention to how people were shaping landscapes, changing them, and thus changing really everything about living in those areas.

KAK: When Wilder is sharing these stories of her youth, how accurate are they to the timeline of what is actually happening on those days in the 1870s?

BB: There are a couple things to keep in mind. One is that she was 60 to 70 years old when she was writing these recollections of her childhood. And the other is that they are historical fiction. So while they feel very realistic, and we know they are rooted very deeply in the actual events of her childhood, there are artistic choices, narrative choices that she intentionally took to move her story along as opposed to reflecting the exact precision of facts as she could remember them.

That said, in most parts of the book where weather is prominent, her recollection of things is pretty accurate, or at least close enough that we could look at the conditions and say, “You know what? Something like this probably did happen during her childhood.”

KAK: You talk about how Wilder touched generations of readers, and part of that gift is really paying attention to how the world around you is changing. How should we be part of this weather narrative and tell stories of weather events in our past?

BB: Like Laura, we can be a part of keeping the record of what happened, and there are ways to do that a little more formally and by the numbers. You can become an observer for the CoCoRaHS precipitation network, submit a daily precipitation total, and that goes into the database just the same as all the other data we collect, but it’s done in your own backyard.

You can also be a person who documents and observes plants and animals and their seasonal behaviors — so when certain species of birds return on migration, for instance, or when certain species of trees or flowers emerge in spring. One source to do that through is the National Phenology Network, where you can collect those observations.

Also, people can keep those stories themselves — when a bad storm hits, or a nasty winter, or … a very mild one, to take a few minutes to write that down. Write a little journal entry or a blog or a Facebook post or whatever means you have that you like to write in. Those stories become part of the collective, too, and help fill out that data to really tell the story of what it’s like to experience it. These are things we can still do now, can continue to do in the future and I think are important to do so that when our next generation looks back, they have some reflections on what the weather was like in our time, because almost certainly it’s going to be different for them.