Joshua Jelly-Schapiro is the author of the books Island People, Names of New York and a forthcoming book on Harry Belafonte, part of Penguin Press’ Significations series edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. This remembrance of the singer and Civil Rights icon, who died in April, is based on his research and interviews with the artist.

The village of Aboukir, in the green hills that line Jamaica’s north coast, is a scattering of humble homes. It’s in St. Ann Parish, a part of the island best known for being where Columbus first landed in Jamaica in 1494, and for a pair of native sons who became world famous much later. One of these is Marcus Garvey, the jazz-age activist who grew up in St. Ann before he went to New York and, as a founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, popularized the idea of the “African diaspora.” The other is Bob Marley, who was born and later laid to rest here, in a hamlet that’s now frequented by sandal-clad tourists in thrall to the reggae legend’s music and memory.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Aboukir, a few hilltops over from Marley’s hometown, isn’t a place that any tourist comes. But the village has its own claim to fame: It’s where a third son of St. Ann’s hills who became a global figure in the 20th century, Harry Belafonte, spent a formative chunk of his boyhood.

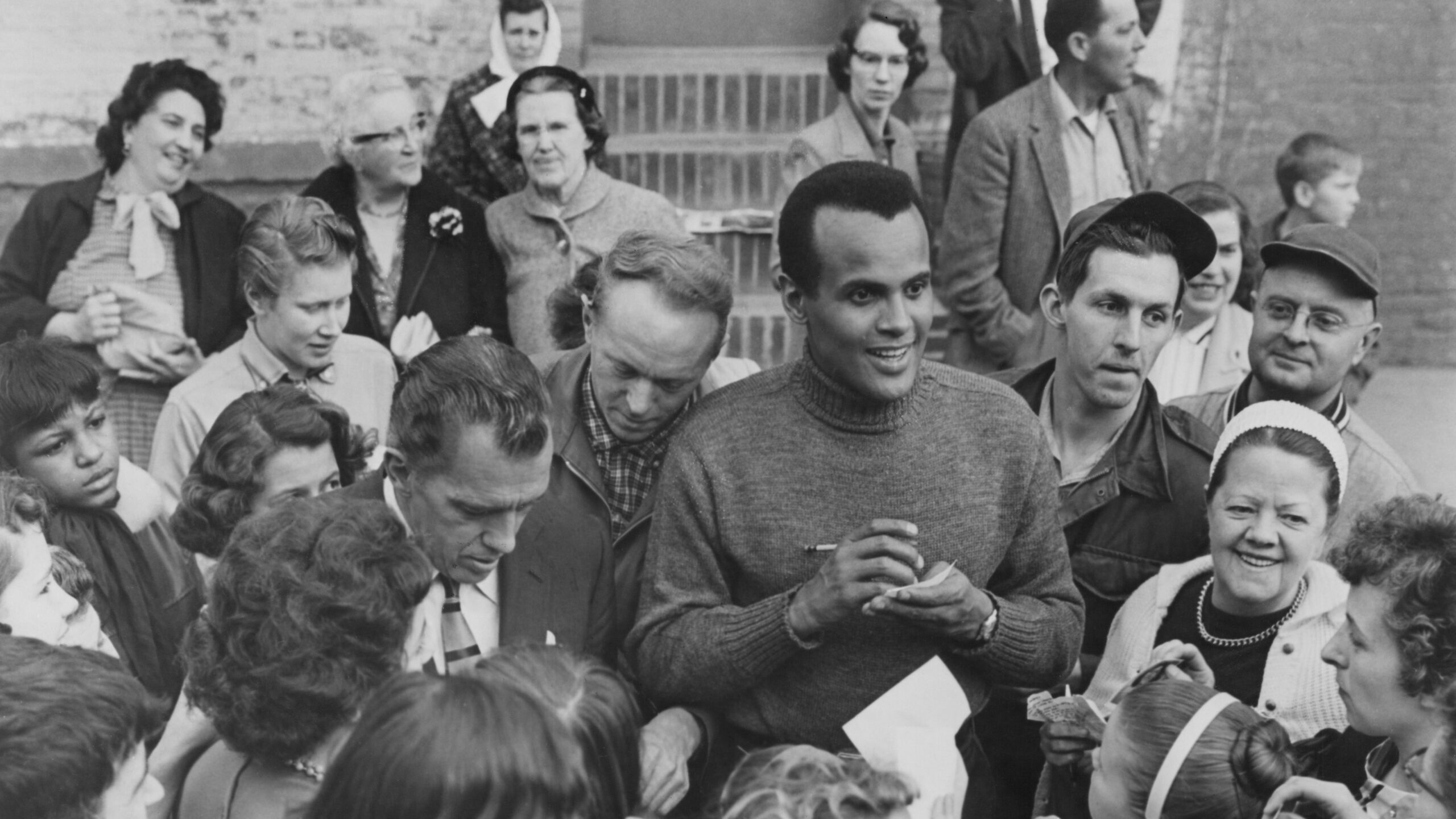

Since Belafonte’s death earlier this year at 96, tributes to his monumental life have been dominated by his legacies in the United States. This is the country where he was born and left his deepest marks: by releasing an album of ersatz Caribbean folk tunes, in 1956, that became one of the first LPs by a solo artist to sell a million copies; by being the first Black man to become a sex symbol for mainstream America; by using his resulting royalties and fame to bankroll Martin Luther King’s movement for Civil Rights; by acting as an crucial conduit, as an intimate of Robert Kennedy, between King’s movement and the federal government. And that was just his heyday; his American story also includes chapters, later on, as a pathbreaking guest host of The Tonight Show; as the producer of “We Are the World” and of Beat Street; as an elder radical and moral scold who is also well-recalled, by those of us who grew up in the 1970s and ’80s, as a genial fixture on Sesame Street.

But it’s impossible to understand Belafonte’s larger meaning, as not merely an American figure but a diasporic and global one, without understanding his Caribbean roots. The Jamaican villagewhere he stayed with his grandmother as a boy, amidst St. Ann’s old plantations, was an out-of-the-way corner of a region to whose islands were trafficked the majority of the 10 million enslaved Africans who, between Columbus’s arrival and the 1800s, endured the Middle Passage — but also a place, like communities across this region “where globalization began,” that’s been shaped for centuries by cultural mixing, long-distance trade and the worldly outlook of its people.

Belafonte was born in Manhattan in 1927, to a young Jamaican immigrant who grew wary, as she tried to make rent as a domestic in the Depression, of the trouble her hot-tempered son was finding on New York’s streets. She sent him to her home island for “safekeeping,” as he’d later describe it, on one of the banana boats that the boy’s father, traveling between the West Indies and the States, worked on as a cook. The village where his mum had grown up, and where her own mum still lived, was named by Jamaica’s old British owners for the town in Egypt where Horatio Nelson defeated Napoleon. But its moniker is pronounced “Ah-boo-ka” by locals who are descended from those the British brought to populate this corner of their empire: enslaved Africans, mostly, but also Scottish overseers and laborers like the forebears of Belafonte’s white grandmother.

Some years ago, while on a trip to Jamaica, I tracked down some of Belafonte’s maternal cousins in Aboukir, and wrote him a letter about meeting his kin there. He replied warmly and, after arranging to meet for lunch near his home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, reflected over a plate of clams on how his Caribbean identity had aided his success in Eisenhower’s America. Harry and his best friend Sidney Poitier — Poitier grew up in the Bahamas; the pair met as young stagehands in Harlem — were able to break taboos, in Hollywood and beyond, unthinkable to Black contemporaries who were less foreign-seeming than Poitier or darker-skinned than Belafonte. Harry’s white fans who embraced his sunny songs of the islands, he agreed, were much more able to imagine welcoming into their homes the “Caribbean gentleman” whose image they both cultivated — exotic and charming, proper and safe — than Black American entertainers who, descended from Dixie’s slaves, carried more threatening baggage. Also, there was this: “When me and Sidney were coming up, people took the way we carried ourselves as proud, imperial. But that’s every f***ing Jamaican I know! And a lot of them are a pain in the ass!”

Imperial bearing and all, Belafonte’s brilliance as a performer was as a translator of folk histories, and the lives of working people, into the idiom of pop. In Jamaica, where Marcus Garvey’s devotees included Belafonte’s mother, Garvey had addressed slavery’s legacies by advocating for “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad.” Bob Marley would confront the same history’s scars, a couple of generations later, by espousing a religion — Rastafari — built from Garvey’s ideas. Belafonte, who came of age at the century’s heady midpoint, collected stories. He didn’t write his own songs; he mediated others’. For this, some purists gave him flack. But it was as a mediator of culture and enactor of songs — carried by his gorgeous voice, lent the glamour of his person — that he brought the stories of his people to the world, and changed it.

When I tromped through St. Ann’s hills to find his kin, I was working on a book about the Caribbean’s unheralded roles in shaping modern world culture. It was a project whose aims Harry loved, and that he supported not merely by granting me interviews, but by taking my prompt to consider how his island roots had shaped his will to succeed — and his wider resonance. “People from the Caribbean did not respond to America’s oppressions in the same way that Black Americans did,” he told me. “We were constantly in a state of rebellion, constantly in a state of thinking way above that which we were given.” That immigrant’s determination, no doubt, aided his rise. And nothing so shaped his influence as his performance-cum-translation of these islands where ethnic mixing and engaging history’s weight have long been facts of life, and whose people have long had a way of punching above their weight.

Belafonte got his start in show business, after a stint in the Navy during World War II, while working as a janitor in Harlem. There, he happened into the American Negro Theater and, determined to become an actor, enrolled in The New School downtown; with the help of the G.I. Bill, he studied with peers like Tony Curtis and Marlon Brando. His first forays into music came singing jazz. But it was the burgeoning folk scene, in Greenwich Village in the early ’50s, that gave him his metier.

Already an ardent leftist, Belafonte was entranced by how leading figures of the “folk revival” — Woody Guthrie and Josh White, Pete Seeger and The Weavers — turned songs of working people into an ally of struggle. Crucially, he and his manager Jack Rollins also saw from the start how Belafonte — charismatic and strikingly beautiful; unencumbered by a guitar and dressed in tight black pants — could take folk music up off its stool, so to speak, and make the presentation of dusty old songs an occasion for dynamic modern theater. From the first time he tried out this new act at the Village Vanguard, it was clear it would work. In 1953, he was cast on Broadway in John Murray Anderson’s Almanac, and stole the show by belting folk songs –– “Mark Twain,” “Hold ’em Joe” — that won him a Tony. “He was an actor,” wrote a critic for Metronome, “playing the best role he was ever to get: the role of a singer.”

To find material and expand his repertoire, Belafonte visited the Library of Congress, as he recounted in his wonderful 2011 memoir, My Song. He also met the great Jamaican folklorist and singer Louise Bennett at the Village Vanguard. “Miss Lou’s” 1954 recording of “Day Dah Light,” a favorite of Jamaican stevedores who loaded banana boats at night to avoid the sun’s heat, singing of how morning’s arrival would send them home, beat Belafonte’s version to the punch by two years. And then, thanks to his friend and collaborator Bill Attaway, he met a fellow New Yorker with West Indian roots who became the essential co-creator of his Caribbean songbook. Irving Burgie, of Barbadian descent but raised in Brooklyn, dubbed himself Lord Burgess at the Vanguard. He shared Belafonte’s affinity, as a gifted lyricist and composer, for turning the folk sounds of the Antilles into northern pop.

In Belafonte’s onstage patter in his heyday, he liked to talk about how he’d learned “Jamaica Farewell” from sailors leaving Kingston’s docks. He didn’t: “Jamaica Farewell” was penned by Burgie in 1955 (albeit with a melody borrowed from the old Jamaican mento tune “Iron Bar,”as Burgie was later forced to admit in court). A similar story lies behind the song that became his signature. The lyrics and melody of “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” were borrowed from the folk version recorded by Miss Lou and others, with the exception of one odd change: Where the old work-song referenced banana “hands” — as bunches of the fruit are logically called — Belafonte’s version invoked another appendage (“Six foot, seven foot, eight foot bunch!”). And it wasn’t Bennett but Burgie who copyrighted those lyrics, and got rich off the publishing. (Burgie went on to co-write other Belafonte favorites like “Island in the Sun,” as well as Barbados’ national anthem.)

More complex still was Belafonte’s relationship with the island — Trinidad — where calypso was born, and whose music bore only a glancing relation to the sounds on his album Calypso, whose success prompted thoughts that a “calypso craze” would supplant U.S. teens’ love for rock and roll (“Warning: Calypso Next New Beat; R.I.P. for R’n’R?” trumpeted Variety in 1957). Belafonte corrected reporters who called him the “King of Calypso”: That was a title reserved for victors in Trinidad’s annual Calypso Monarch competition, during the island’s famous yearly carnival. (Some on the island called him a phony; others were grateful for the attention he brought them.) But he befriended a few greats of the form, among them Lord Melody, the calypsonian whose “Mama Look a Boo Boo” he transformed into an American hit. Harry also helped Melody tour the U.S., as he later would singers like South Africa’s Miriam Makeba and Nana Mouskouri from Greece, key figures in the inchoate genre of “world music” whose rise he did much to foster.

None of this would have happened if it weren’t for his breakthrough album. Calypso spent no fewer than 31 weeks atop the charts, after knocking Elvis Presley from that perch in September 1956. Before Calypso, the 33 1/3 long play format had been dominated by Broadway cast recordings such as Oklahoma and South Pacific. The concept of immersing listeners in a foreign world over the course of two 20-minute sides wasn’t totally new: In the early ’50s, “exotica” and sound effects records were hugely popular, and RCA Victor’s head at the time, George Marek, had helped create the label’s top-selling “mood music” series. Other RCA executives felt the idea would never fly with white listeners, but Marek was convinced by Belafonte’s vision for a full record of Caribbean folk songs, lushly arranged and recorded by RCA’s top engineers. He would be more than vindicated by the success of an album that, as Belafonte later put it, “proved that Americans were more ready than had been assumed to hear the voices of others or the culture of other people.”

By the time Calypso hit, Belafonte was also a movie star: He’d wooed Dorothy Dandridge in Carmen Jones, and would soon woo Joan Fontaine, more controversially, in Island in the Sun. But he was reluctant to accept roles that didn’t, to his mind, match his ideals. Some of the films he turned down, as he never tired of reminding Sidney Poitier, abetted Sidney’s rise: For Harry, projecting genial dignity in public was one thing; it was another to play an unthreatening Negro who’d been invited to dinner by white folks because he wouldn’t upset them. He loved recalling the outlaws with whom he came up in Harlem, and the later film work he enjoyed best — from Uptown Saturday Night to Robert Altman’s Kansas City — found him playing gangsters. Back in Jamaica, his best-loved movie was a western he made with Poitier: In 1972’s Buck and the Preacher, he played a tobacco-spitting huckster who joins forces with a stoic wagon master, in 1860s Kansas, to outwit a posse of white bounty hunters threatening a group of just-emancipated slaves crossing the frontier to freedom.

Belafonte didn’t achieve pop stardom, or arguably even his level of import to the Civil Rights era, by singing “We Shall Overcome.” He did so by performing folk songs from the West Indies — and also “Danny Boy” and “Hava Nageela.” His fondness for the latter material dated from his cherished exposure, as a New Yorker, to both Irish bards and the Jewish comics and cantors who helped him, he once told an interviewer, “[come] to know the Jew through the culture of the Jew.” After his return to Harlem from Jamaica in his teens, the resonance he found in the plays of Sean O’Casey and the stories of Shalom Aleichem, he said, “made me see how relevant these people were to my world — and how relevant I was to theirs.” He loved to joke that, when he affected an Irish brogue to perform O’Casey’s lines, he was just adapting a Jamaican lilt to other means. And his integrated repertoire reflected a determination to reach beyond the protest song, to seek “another way to move my image and my cause through the ranks of the human family,” as he put it in My Song. What better way to unsettle prejudice, and ask discomfiting questions of people who had denied Black humanity, than by lending his voice to the beauty in their own?

In Harry’s old-school politics, the “human family” mattered. But until the end, his worldview was shaped by having traveled between Harlem and Jamaica, and sensing that something profound joined their people. He remained, until his life’s end, deeply engaged with the politics and people of Africa — where one of his earliest achievements, after he was asked by John Kennedy to help launch the Peace Corps, involved organizing an airlift from Kenya that included the father of one Barack Obama. That personal tie didn’t stop Belafonte from criticizing the moderate policies of America’s first Black president — a politician who became a totemic figure to American liberals in ways it’s hard to imagine happening if Belafonte, decades earlier and evincing a similar mien and grace, hadn’t done so first.

Ever the radical, Belafonte was known in his latter years as much for his politics as his music. Among the projects of which he was proudest, from that last chapter, was The Long Road to Freedom — a musical endeavor which had its start when Belafonte convinced George Marek at RCA to back an ambitious box set he conceived back in the ’50s. The collection, which Belafonte began recording in 1961 and worked on for a decade, aimed to recount the larger saga of Black people in Americafrom the arrival of its first slaves until the 20th century. Subtitled An Anthology of Black Music, it featured Belafonte and friends like Bessie Jones and Brownie McGee, with Nigerian drummers and soaring choirs, performing 80 songs from across the Americas and Africa.

After RCA and Marek lost backing for the project, it was shelved for decades. When it finally was released, it was on CD rather than the planned five vinyl LPs, and debuted on the inauspicious date of Sept. 11, 2001. Yet when describing The Long Road to Freedom to a journalist the following year, Belafonte sounded not an ounce less committed. He insisted, as he had done for decades, on the centrality of Black culture to American history, and on connecting Black Americans to a larger diaspora whose foremost exponents have often hailed from the Caribbean.

“Look at the beauty of this music, listen to these voices,” he said. “And if you like what you hear, if you are moved by what you hear, doesn’t that make you want to know more about how this music came to be?”

Sarah Knight and Nicolette Khan contributed research support to this story.

9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))

© Copyright 2026 by NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))