Using fruit flies, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are uncovering a new way to think about treating an aggressive and deadly form of childhood brain cancer.

By understanding how different proteins affect genetic mutations in the flies’ wings and eyes, the researchers say it could lead to new ways to silence genes behind the disease.

Pediatric diffuse midline glioma is a cancer that develops in the spinal cord and midline structures in the brain. It’s impossible to remove, and radiation treatments only extend a patient’s life by months or a few years.

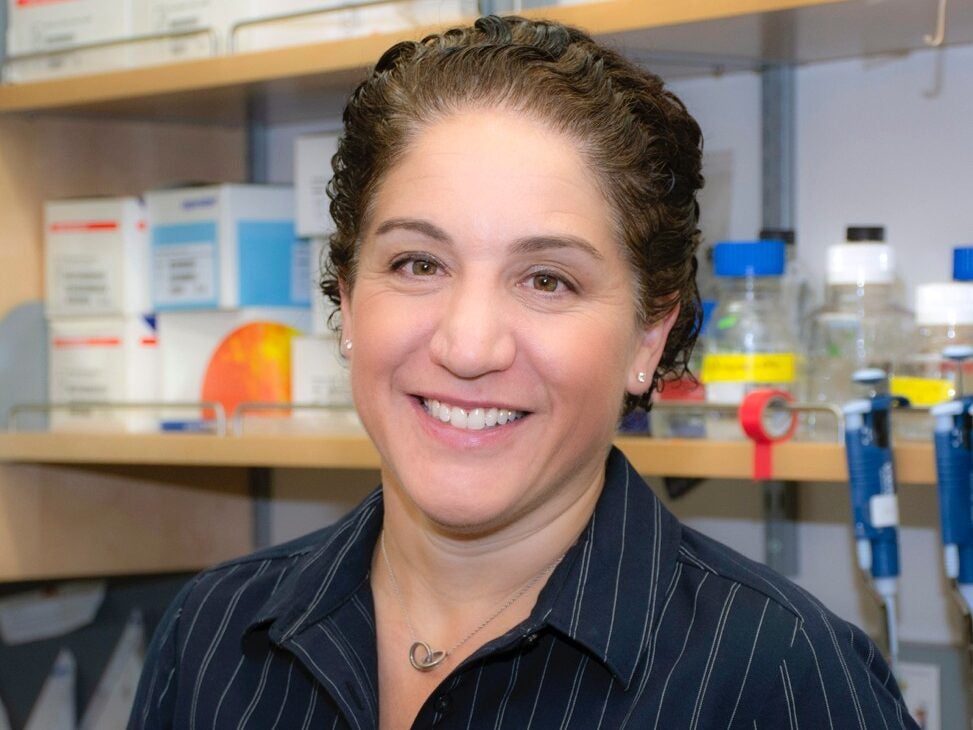

In the face of those stark realities, UW-Madison Department of Biomolecular Chemistry Professors Melissa Harrison and Peter Lewis decided to think outside the box to come up with new treatment strategies.

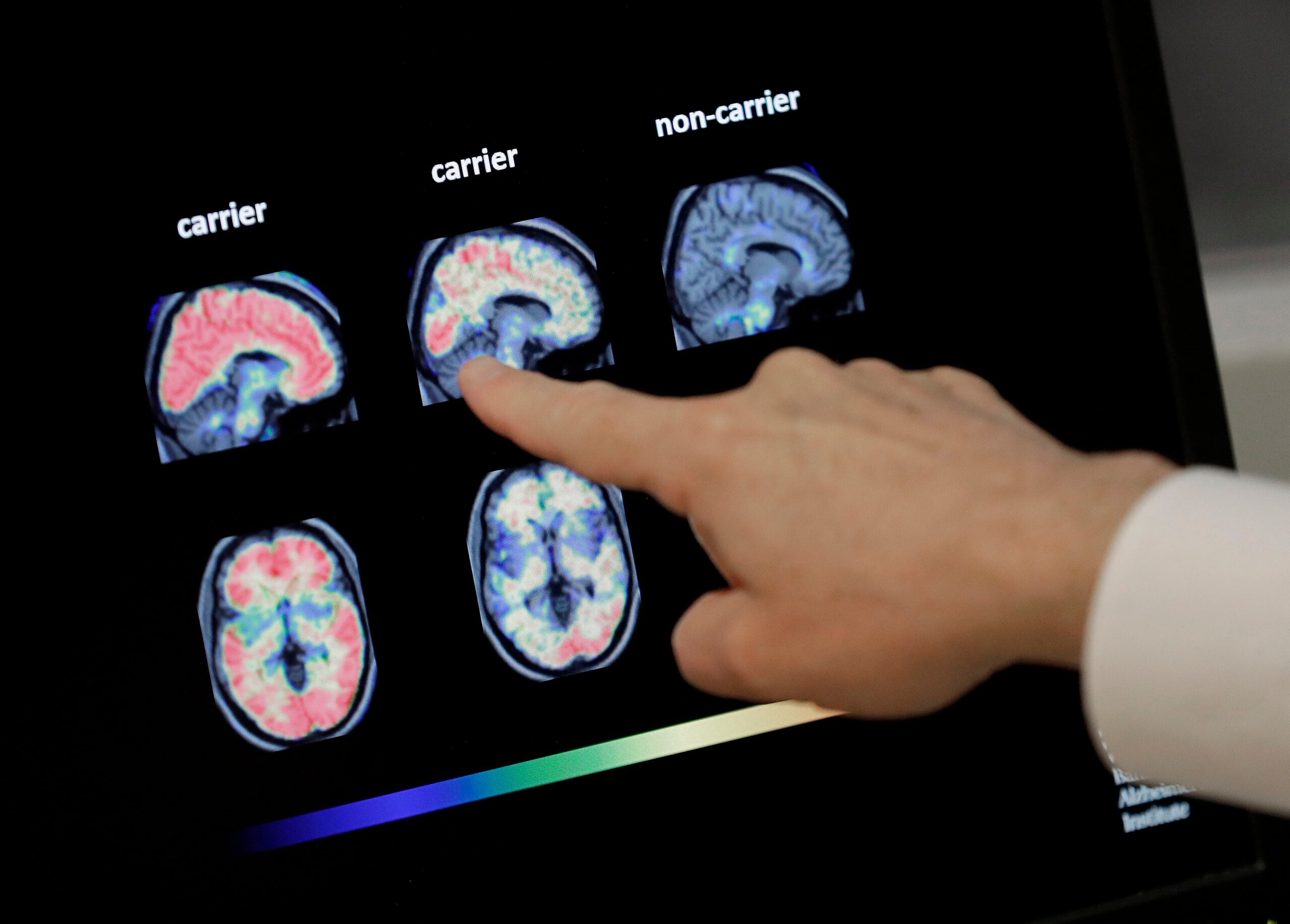

Lewis said the disease is caused by genetic errors but also by changes in how proteins and DNA are packaged in a complex web called chromatin within a cell, which regulates whether a specific gene is turned on or off. With pediatric diffuse midline glioma, Lewis said prior research found mutations in specific proteins in that architecture can cause a cell’s development to stall, and “the tumor then behaves as if development never ended.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

He said researchers are learning more about how chromatin circuits “have been rewired,” and the goal is to identify what types of treatment “might be effective at treating these tumors.”

Enter the fruit flies. Hundreds of them.

Harrison leads a lab using fruit flies to study cell development in humans. She told WPR that two-thirds of the genes that cause cancer in humans are shared by fruit flies.

Because fruit flies have very short life cycles, Harrison and her team were able to screen 438 of those shared genes and manipulate proteins to cause developmental defects in the flies’ wings and eyes. By screening hundreds of other genes in the flies’ DNA, they found new pathways that either worsened the defects or made them better.

“It’s generally easier to design drugs that inhibit the function of a specific protein than it is to promote normal expression or normal function,” Harrison said. “So in this case, we were looking at things that when we inhibited the function, it restored normal development.”

In a nutshell, Lewis said it’s an easier way to think about targeting and inhibiting the protein mutations that cause the deadly childhood cancer.

“These results point to therapeutic strategies that aim to rebalance gene activation and gene silencing,” he said.

Lewis said the data from the fruit flies gives researchers “a short list” of cells from human patients and mice to begin testing on.

The research effort was funded in party by the National Institutes of Health and the University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.