Prestige TV creator David Simon takes us inside his HBO mini-series, “The Plot Against America,” based on the Philip Roth novel. Also, musician Eef Barzelay talks about his career in and out of Clem Sinde. And author Sam Wasson on the Holy Grail of 1970s cinema, “Chinatown.”

Featured in this Show

-

David Simon On Adapting Philip Roth For HBO’s 'The Plot Against America'

David Simon is one of the founding fathers of prestige television. He created, along with Ed Burns, HBO’s groundbreaking series “The Wire” — which is argued by many to be TV’s greatest drama. He’s followed that up with two more critically acclaimed series — 2010’s “Treme” about post-Katrina New Orleans and 2017’s “The Deuce.”

Simon has also adapted many works of nonfiction for HBO mini-series including “Generation Kill,” “Show Me A Hero” and a televised version of his and Burns’ own ethnographic book “The Corner.”

But, until now, Simon has never adapted a work of fiction. And he has set the bar pretty high for his first crack at it by adapting Philip Roth’s “The Plot Against America” as an HBO mini-series.

“It was a little mortifying because it was Philip Roth. I mean, this is a lion of American literature,” Simon told WPR’s “BETA.” “The books that I had adapted, and quite faithfully I think, were all works of nonfiction, so I couldn’t take liberties. There was a real moment of mortification whenever we decided to change something or omit something.”

Roth released the novel in 2004 and while many took it as a commentary on the Iraq War, Simon initially treated it simply as a fascinating, well-researched thought experiment.

“Some people think he was writing to the allegory of George Bush, but I don’t think so, and I think (Roth) denied it. I just thought it was an artifact of history,” he said. “It was an interesting alternative view of what might have happened at a critical moment in American history.”

In fact, when Simon was first approached to adapt the novel in the wake of President Barack Obama’s second inauguration he re-read the book and thought it felt even more dated. Simon argues Roth’s work is far more resonant now given our current political moment.

“Philip Roth seemed to have nailed that without even knowing about Trump or without predicting this future, he nonetheless nailed it in the novel,” Simon said.

The novel outlines an alternative history where Charles Lindbergh is the 1940 Republican candidate for president and wins the election over Franklin D. Roosevelt. Lindbergh plays up American isolationism and takes a sympathetic stance with Nazi Germany to keep America out of World War II that leads to a growth in American anti-Semitism. It’s written semi-biographically through the eyes of a 10-year-old Philip.

“Philip Roth used his own family as the narrative force to explain this dry run at American fascism,” Simon explains. “He imagined the events of his alternative world colliding with the lives of his parents, his older brother and himself, as well as some extended family members. So you experience this totalitarian maneuver and this Lindbergh administration and all of what goes awry in America from the point of view of this one lower middle class family in Newark, New Jersey.”

Simon, himself the son of working-class Jews, was drawn to the sentiments of how fragile democracy and freedom could be. The tagline for the mini-series — “Freedom is never completely won, but it can be lost” — was a direct quote from his father, Bernie.

“My father was the public relations director for the B’nai B’rith Jewish Service Organization for about 30 years,” he said. “Before that, he worked for the Anti-Defamation League. He was basically a professional Jew.”

Simon recalls nearly 50 years of Passover celebrations where his father refused to let the Jewish holiday of freedom go by without reiterating that argument.

“He would always point out that democracy and freedom; these are things that are never completely won. That every day you have to go out and kill a few more snakes. Every day you have to assert for the rights that you have,” Simon said.

In the mini-series, Simon’s adaptation does take the aforementioned liberties from the book at both Roth’s request and with his permission. The Roth family has now become the Levin family and the series follows the perspective from multiple members of the family and not just Philip’s character.

“There are a couple of big changes, one of which was we had to go to points of view that were beyond 10-year-old Philip, who is remembering his childhood from adulthood, which is the structure of the book,” said Simon who collaborated with Roth before the author’s death in 2018. “That’s just too much voiceover for any film to carry successfully. We had to expand the point of view to all the other family members. And by doing that, we opened up the mini-series so that it can cover more ground. Roth saw that right away and agreed that that was the way to go.”

Simon also claimed that the ending of the novel was a little too “magical” for television and revised it to fit the medium better. He said that bringing that recommendation and his revised ending script pages to Roth was a bit daunting.

“I sat there while Philip Roth, great man of literature, read those two pages over again. It was probably four or five minutes. It felt like it was four or five hours while I was sitting there. And finally he closed the book, and he looked at me and said, ‘Well, it’s your problem now.’ So I took that as permission,” Simon recalled.

Simon and Roth were set to do site locations for the shoot when the author died. While Simon was deeply saddened by the legend’s passing, he admitted to “BETA” he felt a little relief he didn’t have to share further adjustments to Roth.

“I will confess to something. When he passed away, the coward that is latent inside as a writer immediately said, ‘Well, at least I don’t have to do that.’ After we finished filming it, after we were done, I think we honored what was important in the novel in very, very key ways,” said Simon. “I’m embarrassed to cop to it now, but I have to admit to it, I was scared. I was scared of showing him the pages.”

Simon now wishes he could share the finished adaptation with Roth to see what the author would make of it.

“Now I would be curious to show it to him and get his reaction. You know, for better for worse, now I wish he was here in every sense,” he said.

“The Plot Against America” can be streamed anytime online at HBONow.

-

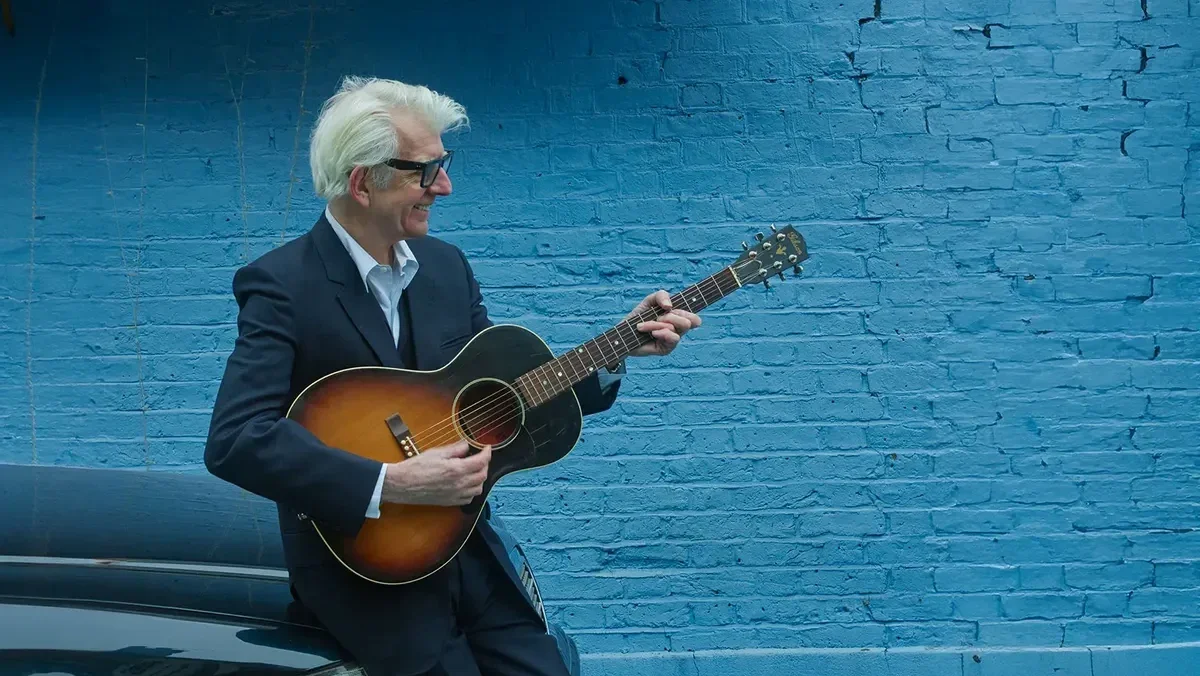

Songwriter Eef Barzelay Embraces The Unknown, Endures Through Music

Eef Barzelay has navigated the ups and downs of a career in music for more than 20 years.

“So it’s like surfing, you know, just trying to stay the board,” he said. “You know, wait for your wave and then hope you don’t get knocked off the board.”

He recently spoke with Doug Gordon of WPR’s “BETA” about the long and twisted path of his band Clem Snide, and how embracing the unknown brought him to the release of his new record.

Clem Snide’s just-released “Forever Just Beyond” ends a five-year hiatus for the band, and marks a new beginning after what Barzelay described as “my decade of despair.”

But back at the turn of the century, things were really looking up for the band. The Snide’s first three albums, “You Were A Diamond,” “Your Favorite Music” and “Ghost Of Fashion” had cemented them as indie, alt-country mainstays. Their 2001 song, “Moment In The Sun,” was even featured as the theme song for Season 2 of the NBC comedy “Ed.”

However, as the decade progressed and Clem Snide continued releasing music, things got more complicated. Core members started dropping out to start families and pursue other goals, and Barzelay had a bitter, costly breakup with his former manager.

“Well, you know, it was kind of a slow-motion accident,” he said. “But yeah, by 2010, I was the last man standing.”

“And so here we are. I mean, my wife, two small kids, and we went into foreclosure,” Barzelay continued. “And so I had to declare bankruptcy.”

So he adapted.

He started offering his songwriting services through his website, writing and recording personal songs for loyal fans (full disclosure: I hired Barzelay to write a song for my wife on the occasion of our 10th wedding anniversary).

He said that interaction with fans was really helpful.

“I’ve found that the more songs I wrote for people, the more songs I wrote just in general,” he said. “You know, it just, it opened up that portal ever wider.”

But difficult decisions loomed.

“See, my thing is, I can’t do anything else. I really feel like I was called to do this,” Barzelay said. “But the darker side of that is maybe I’m just doing it because I don’t want to do anything else, which is also true. So I wrestle with that.”

“But I have always worked through that process by writing songs, like, no matter what I’m going through, I always write my way through it,” he concluded.

Along the way, he noticed things fell in to his lap in the nick of time to save his family and keep the music going.

“In 2015, don’t even ask me how I ended up with this gig, but I wrote a little turnaround for Chobani Greek yogurt, and for about four to six months I was the voice of Chobani Greek yogurt,” he said.

And the next year, a fan sent him a video from an Avett Brothers concert of Scott Avett playing an obscure Clem Snide song during an encore.

Barzelay reached out to Avett and quickly heard back.

“Yeah, I just kept sending him songs,” Barzelay said. “I just was trying to entice him to work together and to maybe make a record, and he agreed. You know, what an angel.”

Eef Barzelay and Scott Avett. Photo courtesy Missing Piece Group The result is the just-released “Forever Just Beyond.”

“I look up to Eef with total respect and admiration, and I hope to survive like he survives: with total love for the new and the unknown. Eef’s a crooner and an indie darling by sound and a mystic sage by depth. That’s not common, but it’s beautiful,” Avett said in the album’s press release.

The first song on the album is “Roger Ebert”, which was inspired by an interview Barzelay read with Ebert’s wife after Ebert’s death in 2013.

“And she just talked about the experience that he was having in those last few moments,” said Barzelay. “And he really did seem to start to kind of see behind the curtain, you know, and he was writing her notes that said it’s all an elaborate hoax.”

“And that feels right to me. You know, I mean, I’m not a religious person,” he revealed. “But the thing I like about religion is religion gives you a way to turn your sorrow in to grace. So I like to advocate for spirit, not so much for body, you know, because I think we get too much body, not enough spirit in the culture.”

The song “Easy” shows up a little later on the album, and features the lyric, “It’s easy to say you would never sell out when no one has made you an offer.”

The song feels like a darkly humorous summation of the last decade for Barzelay.

“We all have these false ideas about ourselves. We all think we’re good. We all think we’re brave, and we all think we’re right. And in a way, you never really know yourself unless you’re tested,” he explained. “So you know what I’m saying? Like, the point of life in a way is to suffer. It’s to turn your suffering into grace.”

After all of his ups and downs, and with this new “miracle” record in hand, Barzelay thinks it’s his love for writing songs that’s helped him through.

“Writing a good song is always the most therapeutic thing there is for me,” he said.

And he’s thankful his fans are still connecting with his songs.

“It’s like if a tree falls in the forest and there’s no one there to hear it: It actually doesn’t make a sound,” he said. “I can solve that ancient riddle: it doesn’t. Believe me, I know firsthand; if there is no one there to hear it … So this is true of songs. They live inside of other people’s brains and hearts and souls.”

-

How 'Chinatown' Changed Detective Movies For Good

Screenwriter Robert Towne pitched the idea for “Chinatown” to his longtime buddy Jack Nicholson on Quincy Jones’ tennis court.

“Towne hasn’t had a breakout. He’s had some small success,” author Sam Wasson told WPR’s “BETA.” “And Nicholson is although a movie star, not a leading man. So Towne says to Jack, ‘I am going to write you a part that will make you a leading man with a love story.’ Nicholson’s response was ‘Whatever you want, Beaner,’ which is what he called Towne.”

As Wasson writes in his book, “The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollwood,” Towne wanted Nicholson to play a different kind of detective than what moviegoers had seen in film noir and previous detective films.

“If you look at the tradition of (Raymond) Chandler, the most famous writer of detective fiction, certainly one of most famous writers of L.A. fiction, his guy, (Philip) Marlowe had a real morality,” Wasson said. “He was noble. In fact, Chandler even thought of him as sort of a modern-day knight and urban knight.”

“Towne wanted Jake, (Nicholson’s) character, to be sort of a scoundrel, a guy who was really in business, who didn’t really care, didn’t really have a sense of personal values … in a way Towne put it, he would do divorce work, which is dirty business,” he added.

Wasson explained that Marlowe would never do divorce work and that Towne’s vision of the J.J. (Jake) Gittes character would give Nicholson an arc to follow throughout the film.

“He would start as this sort of venal louse and turn into a guy who really has to learn to stand up for something,” Wasson said. “Those of us in Hollywood have to deal with this question of, are we doing divorce work? Metaphorically. I mean, are we doing good work or are we just earning a buck? So it was a story that was close to Towne, close to everyone that Towne worked with, everyone in Hollywood.”

Towne decided he wanted to write a screenplay about the Los Angeles he remembered growing up in as a child, in 1969 — before pitching it to Nicholson. “And the impetus for his nostalgia was the Manson murders, the Tate-LaBianca murders, which changed the city literally overnight. A lot of people use ‘overnight’ to mean maybe a couple weeks, but this is literally overnight,” Wasson said.

Towne based “Chinatown” on the true story of the California water wars. During the 1920s, agents from LA pretended to be ranchers and farmers and purchased land in the Owens Valley area. Residents discovered that LA interests now owned a lot of their water rights. The city used an aqueduct to drain the water from Owens Valley in order to help LA grow.

When Towne learned about this history, he realized LA was built on a crime.

“And not only that, but the criminals get away with it. And not only that, but they’re celebrated because they’re looked back upon as the city fathers. So the ironies of that were terrible and compounded by what was going on at Vietnam and Watergate and Nixon. Our leaders were showing themselves to be bad guys,” Wasson said.

Wasson described “Chinatown” as “the American nightmare.”

“As Robert Towne said, it represents the futility of good intentions. And that is the opposite of the American dream, where good intentions will get you everywhere. ‘Chinatown’ says good intentions will not only get you nowhere, but sometimes they will make things worse off than they were before.‘”

The film also has a shocking twist ending that Wasson said drives the point home that the movie is personal, not just political.

“I do think it’s important, obviously, because it talks about how corruption is not just political. It is personal. And a man like Noah Cross will corrupt anything,” he said. “It really drives the story home for those people who up until that point have been watching a movie about California water rights. It says, actually, this movie is about all of us. It is about the dangers of power down to the domestic. I don’t think anyone saw that coming.”

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Brad Kolberg Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- David Simon Guest

- Eef Barzelay Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.