My mom died of dementia back in 1981; they identified it as Alzheimer’s disease. So anything I can do to prevent Alzheimer’s is something that catches my eye.

That’s just what happened with a new study out of the British Medical Journal. Researchers postulated that a lack of purpose and personal growth might precede mild cognitive impairment and, therefore, Alzheimer’s. It made me take notice.

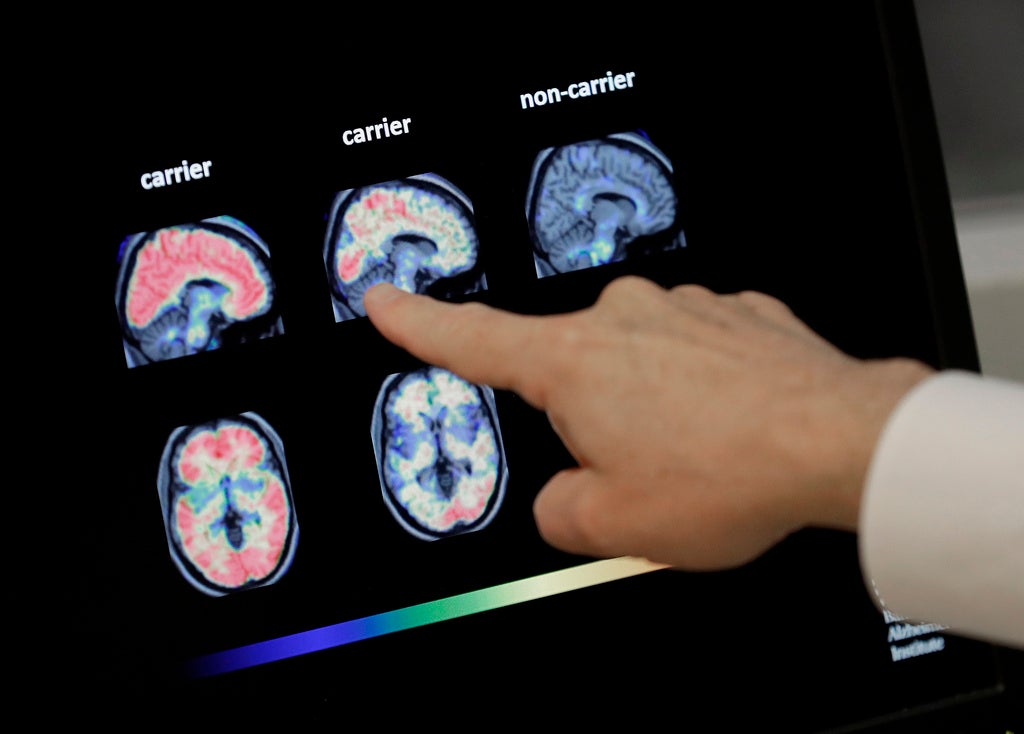

The Memory and Aging Project from Chicago’s Rush University works to identify genetic and environmental risk factors in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. It involves a detailed assessment of risk factors for Alzheimer’s in older people who have no signs of dementia when they start the study.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Everyone entering the study agrees to have an annual in-depth exam, which includes labs, questionnaires and neurological testing. They also agree to undergo a brain autopsy after their death.

From September 1997 through April 2005, more than 1,000 older persons from 30 residential facilities across the Chicago metropolitan area agreed to participate. Their mean age was 81 years. About a third had 12 or fewer years of education and a third were men, meaning two out of three were women.

First, some background on dementia: Some people who get dementia first develop MCI, or mild cognitive impairment, a condition in which people have more memory or thinking problems than others their age.

The symptoms of MCI are not as severe as those of Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias. People with MCI can usually take care of themselves and carry out their normal daily activities. But people with MCI are at a greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, so preventing it is rather critical.

Estimates vary as to how many people who have MCI will develop dementia. Roughly one to two out of 10 people age 65 or older with MCI may develop dementia over a one-year period. However — and this is important — in many cases, the symptoms of MCI stay the same or even improve, and dementia never develops.

So back to what they found in the study. People who felt their life lacked purpose and had few opportunities for personal growth were more likely to develop MCI. This “view of life” risk factor preceded MCI by two to six years.

For years, there has been mounting evidence linking psychological well-being to brain aging, including the development of dementia. This seems to be another nod to that link.

People in the study who had self-acceptance of where they were in their stage of life, felt autonomy with what they could do, were capable of managing their immediate environment and did so, and had meaningful connections with others and the desire for personal growth were less likely to develop MCI.

Now, this result might be bidirectional: In other words, poorer cognition might influence psychological well-being as well as the other way around. Greater well-being and better cognitive function also might share certain protective factors. It’s the classic chicken and the egg question of what comes first.

The researchers concluded, “Our findings indicate that personal growth and purpose in life may be more cognitively demanding than other components of well-being, and therefore may serve as more sensitive indicators of cognitive aging. Moreover, we found that positive relations with others declined rapidly after MCI diagnosis.

“People with impaired cognitive function may be less likely to engage in social and leisure activities than they were previously, which can cause further deterioration in their relationships with friends or others.”

My spin: Social engagement, continuing to learn and pushing yourself to do things appear to be critical in keeping dementia away.

Back when I started medical school, we thought exercise was for jocks, certainly not for older Americans. Yes, you might be out there golfing, but save your heart, take a cart — that was the slogan.

We learned over time that this was the opposite of the truth. Exercise is important throughout the life space. This study shows the same is true for the brain as well as the body.

Staying engaged, staying active and not passive, just might stave off MCI and stop dementia in its tracks. Just like wearing a seat belt can help save lives in a car accident, for older folks having a purpose in life might be akin to drinking from the fountain of youth. Stay well.

This column is the opinion of the author, © Copyright 2026. Dr. Zorba Paster is a family medicine physician practicing in southern Wisconsin. Consult a health care provider for personal health information. The opinions expressed aren’t meant to reflect the views of Wisconsin Public Radio, its employees, the University of Wisconsin-Madison or the Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.

Zorba Paster On Your Health airs on WPR News Saturdays at 1 p.m. and Sundays at 6 p.m.