A group of chemicals known as PFAS are prompting increasing attention and concern across Wisconsin, turning up in drinking water in Marinette and rivers in Madison and elsewhere around the state. What are these chemicals and why are they such a big deal?

What are PFAS?

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

PFAS is a catch-all term for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which is a group of more than 5,000 synthetic chemicals.

Chemicals in the PFAS family have many valuable properties and, as a result, are useful in a wide range of applications. They can make surfaces non-stick or waterproof, so these chemicals are used in furniture, carpets, paper products, textiles, cookware and cosmetics. They are also used in firefighting foams, chrome plating and in the production of fluoropolymers like Teflon.

While PFAS have drawn a lot of attention lately, they are not new — they’ve been in use since the 1940s.

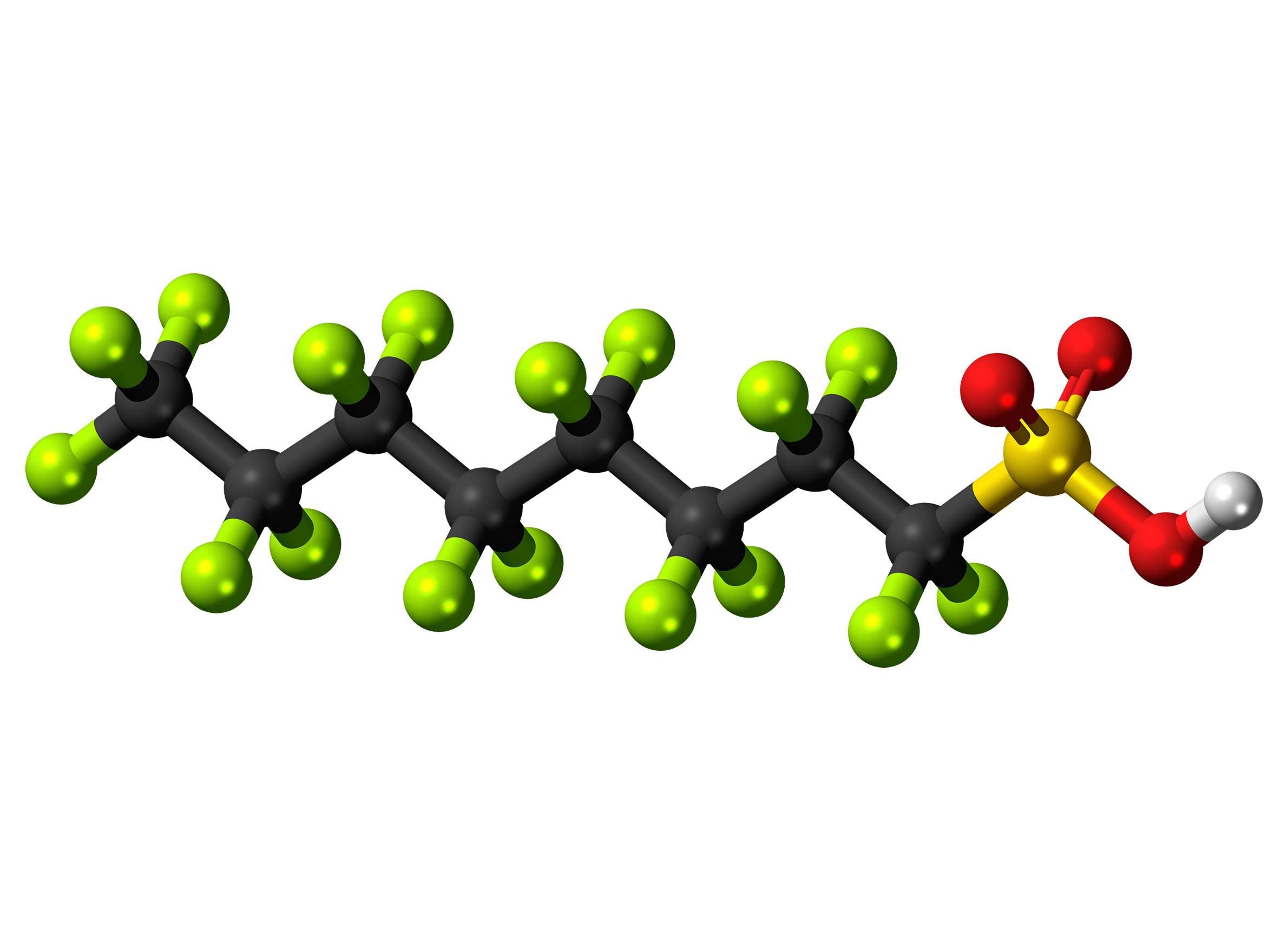

The most commonly studied PFAS and the ones driving potential state regulations are two specific chemicals. PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid) was used to make Teflon, while PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid) was used in the stain and water repellent Scotchgard, among other applications.

Both PFOS and PFOA are no longer manufactured in the United States due to voluntary industrial phaseouts. However, these chemicals persist in the environment, and there are many other PFAS still in use, some of which break down into PFOS and PFOA.

It’s important to remember that thousands of chemicals fall under the PFAS umbrella. This makes it challenging for scientists and regulators to tackle these chemicals because there is so much to study and so many things remain unknown.

Why are people concerned about PFAS?

All of the increasing attention to PFAS is driven by concerns about human and ecosystem health. Some PFAS have been linked to thyroid disease, decreased fertility, pregnancy complications, low birth weights, decreased immune response and increased cholesterol. There is also some evidence that ties PFAS to cancer, primarily among people who lived or worked near contaminated manufacturing locations.

PFAS are also a threat to human health because some chemicals can accumulate in the body. For example, PFOA and PFOS were found in the blood of nearly all people tested in several national surveys.

Importantly, the health effects happen at low concentrations. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a lifetime health advisory level for PFOS and PFOA of 70 nanograms per liter in drinking water in 2016. In Wisconsin, the recommended groundwater standard under consideration is even lower: 20 nanograms per liter for a combined concentration of PFOS and PFOA. Many other states are considering similar limits.

For comparison, trihalomethanes, which include chloroform (i.e., a probable human carcinogen), are allowed to be 4,000 times higher in drinking water in the U.S.

The growing interest in PFAS is driven by increased understanding of their health effects and environmental fate, as well as the ability of scientists to measure these chemicals at the low concentrations that are relevant to human and ecosystem health.

How do PFAS get into the environment?

PFAS are used in many applications, so there are many ways that they can get into the environment. There are also different ways in which humans might be exposed, including consumer products, contaminated drinking water or general environmental contamination such as dust.

Manufacturers might use PFAS and then send their wastewater to the sanitary sewer. Similarly, products containing PFAS might end up in landfills. The contaminated water flowing from the landfill could be sent to a wastewater treatment plant or just end up in the groundwater.

Wastewater treatment plants are not a source of PFAS, but they are also not designed to process the chemicals into safer compounds. As a result, any PFAS that come into a treatment plant typically end up in the treated water or biosolids produced by the plant. In Wisconsin, treated wastewater is typically sent to surface waters, and the treated biosolids are often used as fertilizer on farms.

Firefighting foams are another important source of PFAS in the environment. These foams are often used at airports and military operations, as well as for putting out major fires, such as the transformer fire in Madison in July 2019.

Once PFAS are in the environment, the chemical structure of individual chemicals determines where they end up and how long they last. The structure determines how much of each PFAS chemical will wind up in soil and organisms compared to how much will dissolve in water. For example, PFAS with long carbon chains, like PFOS, are more likely to be found in organisms than PFAS with short carbon chains.

As a group of chemicals, PFAS have many carbon-fluorine bonds. These bonds are very strong and hard to break, meaning that there are not many ways of breaking down the compounds. This is why PFAS are sometimes described as “forever chemicals.”

Where are PFAS found?

PFAS are not just a Wisconsin issue. Since PFAS are used in so many applications, last such a long time and can be transported long distances through the atmosphere, they are found throughout the world, including in remote regions.

PFAS are commonly associated with military sites and airports due to the use of firefighting foams. PFAS are also found in groundwater because many of the chemicals are relatively mobile in the environment.

PFAS are also common in surface waters around the world. The chemicals were first detected in water in the Great Lakes in 2003. PFOS was detected in polar bears around the same time, and there is recognition of these chemicals as global contaminants.

PFAS concentrations tend to be higher in sites associated with a larger population and more industrial activity. For example, there are higher concentrations in the eastern Great Lakes, in Lakes Erie and Ontario, compared to Lake Superior. This pattern holds for PFAS in water, as well as in sediments, fish and birds around the Great Lakes.

The contamination near Marinette is associated with activity at the Tyco Fire Technology Center, which has led to high PFAS concentrations in private drinking water wells as well as nearby drainage ditches.

What is Wisconsin doing about PFAS?

Action to document and respond to PFAS contamination is happening at many levels in Wisconsin, from municipalities to the state to federal agencies.

At the state level, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources is working on multiple fronts to determine the extent of PFAS contamination in Wisconsin, with monitoring of water and fish concentrations in sites with likely contamination. The agency is following successful efforts in other states to identify sources of PFAS to municipal wastewater treatment plants and working to identify responsible parties in known contaminated sites. The DNR is working closely with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services to develop standards for PFAS contamination in groundwater.

Given the active interest in PFAS and the persistence of these chemicals, Wisconsinites can expect to hear much more about them in the years to come.

This report was produced in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin Cooperative Extension. @ Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.