Families across Wisconsin will gather Thursday for Thanksgiving dinner, but probably just a few will be talking about whether to keep living near a large, coal-fired power plant.

It will be a likely dinner table topic, though, for the Michna family, who live in the Racine County community of Caledonia. Their neighbor to the north is the Oak Creek Power Plant, operated by the state’s largest utility, We Energies. The Michnas say decades of nearby coal-burning has been a nuisance, and a health threat.

Spending a little time with the Michnas, on the Caledonia street named after them, one is quickly made to feel at home.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Frank Michna recently welcomed 15 reporters on an energy issues tour with the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources to speak with several relatives he’d gathered.

The family’s history in the area goes back 170 years, and recently it has been marked by a collection of ailments.

“We all have asthma. I mean she has asthma, he has asthma. He has polyps,” Michna said, nodding his head in the direction of various relatives. “I mean we can go on and on.”

Another family member, Andrew Webber, continued the list: “Children who have grown up here have a high degree of strange neuroblastoma and various other diseases.”

“My daughter has Crohn’s, we have Crohn’s in our family, and it’s all digestive type of stuff,” Michna added.

The Michnas contend the problems boil down to two types of pollutants. One is the large amount of soot and other chemicals coming out of the Oak Creek smokestacks, even after more pollution controls were put in when the plant expanded about five years ago.

The second pollutant is coal ash that the electric utility buried in nearby pits decades ago. The Michnas and others contend potentially harmful substances like molybdenum and boron eventually leached into drinking water.

The environmental group Clean Wisconsin has been looking into groundwater contamination near the Michnas’ property, as well as near coal ash landfills and sites where the ash is used in building projects , including highways.

An attorney for the group, Katie Nekola, said she doubts the high levels of molybdenum found at some sites are naturally occurring.

“That’s what the (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources) says. But I think at the levels we’re seeing molybdenum, it’s never found that high (naturally) anywhere,” Nekola said.

Clean Wisconsin scientist Paul Mathewson agreed, saying, “We did a literature research when we were first getting into the project, and if you see levels this high, it’s almost always contamination from a human source.”

Still, he said he’s unable to rule out that it isn’t, “an extremely unusual area,” with high natural levels.

Mathewson said Clean Wisconsin hopes to get a more definitive answer by looking closely at the age of local groundwater. If older and deeper water is also high in molybdenum, it’s less likely that coal ash is the culprit.

We Energies isn’t saying much publicly about the controversy. As part of the same journalists’ tour, the company highlighted one of its other power plants where coal ash isn’t a concern anymore: the Valley Power Plant in downtown Milwaukee. It’s now powered by natural gas and talking points there focused on reduced emissions of greenhouse gases, due to the switch away from burning coal.

But We Energies Vice President Bruce Ramme did take a question about whether molybdenum connected to coal ash is polluting water for people like the Michnas.

“Molybdenum is certainly one of the trace elements that exists in coal ash,” he said. “We have looked at that very carefully, and we do not believe that molybdenum is contributing to any kind of groundwater issues in Wisconsin.”

Clean Wisconsin’s Nekola disagreed with Ramme’s statement when asked for comment.

Ramme also said the company is opposed to possible federal efforts to regulate coal ash as hazardous waste. Environmental groups expect that battle to heat up next year, as is talk in Wisconsin over whether to allow more so-called beneficial reuses of coal ash.

As for the Michnas, they’ll continue to talk — including during Thanksgiving week — about a potential lawsuit against We Energies, or whether the company will try to buy them out. A We Energies spokesperson declined comment on the Michnas, but said over the years , several other properties have been purchased, as a buffer area around the massive Oak Creek plant.

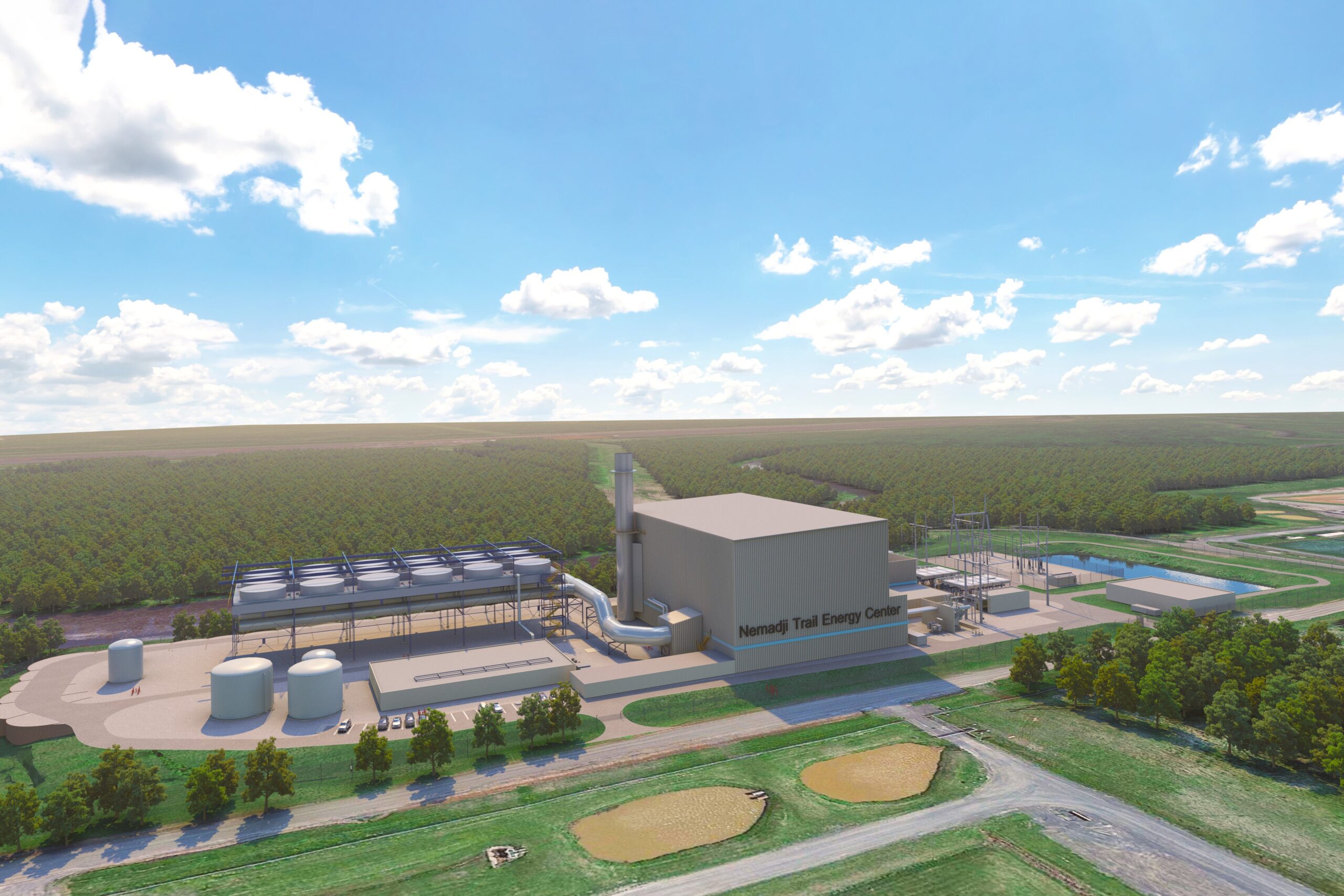

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story included an incorrect photo caption. It has been updated.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.