Local governments across Wisconsin are dealing with increasing debt burdens, according to a new report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum.

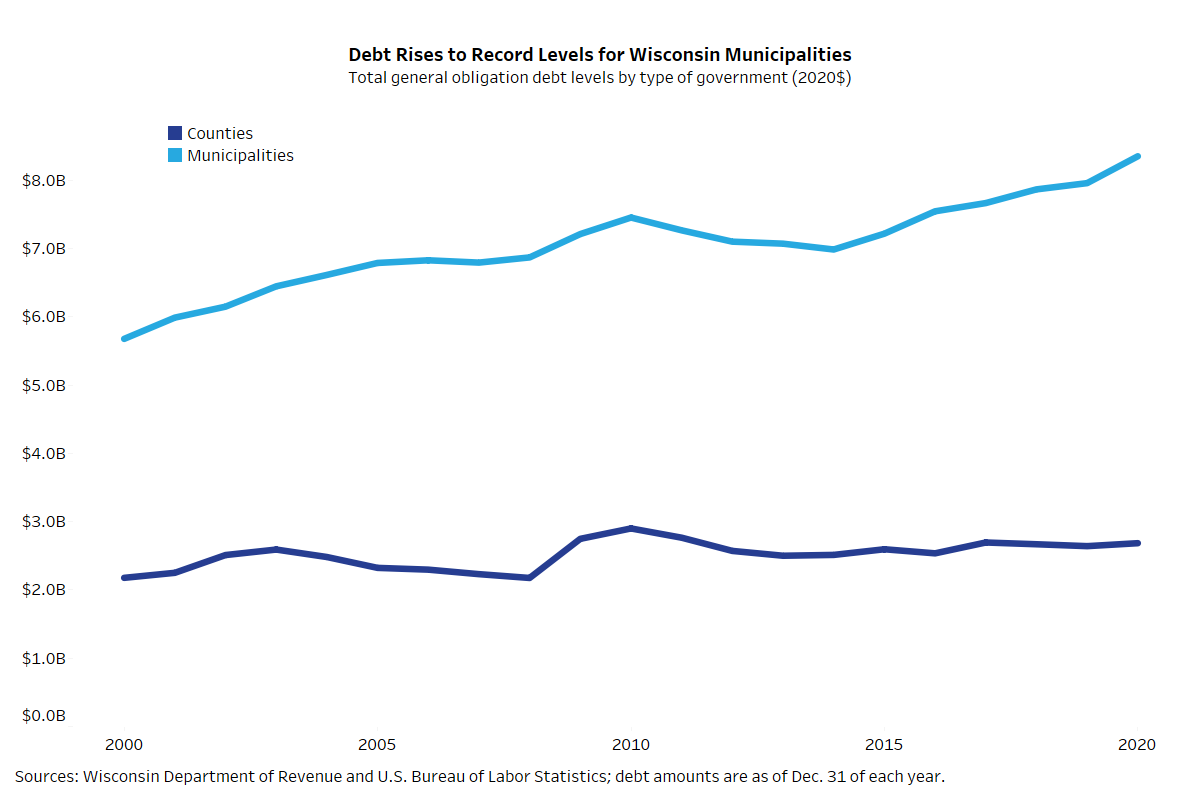

The report found that total debt owed by the state’s cities, counties, villages and towns rose by 5.4 percent to $11.04 billion in 2020 — the highest amount on record.

Cities including Milwaukee, Madison and Kenosha hold the most debt, but Wisconsin towns have seen the fastest growth in borrowing since 2015.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The Policy Forum looked at Wisconsin Department of Revenue data from more than 1,920 local governments from 2000 to 2020. According to the report, on Dec. 31, 2000, local governments owed a total of $5.23 billion — or $7.86 billion in 2020 dollars. Twenty years later, those same local governments owed $11.04 billion — a more than 40.5 percent increase after adjusting for inflation.

Jason Stein is the research director for the Wisconsin Policy Forum; he said the increase isn’t reason to panic, but it is something to keep an eye on.

“That’s not automatically a bad thing. Debt is just an instrument that you use to make investments,” Stein said, referring to building roads or upgrading infrastructure. “But at the same time, when debt rises substantially, your payments on that debt are also going to rise.”

Stein said it becomes problematic when debt payments supersede spending on local services like public safety, parks and libraries. That’s something the city of Milwaukee has dealt with over the last several years — this budget cycle included.

The report points to several reasons why borrowing has grown over the last two decades, including a need to replace aging infrastructure and upgrade technology across the state. Interest rates have also been extremely low.

The report also points to state law that incentivizes taking on more debt.

Levy limits in Wisconsin say that local governments can’t raise property taxes by a greater percentage than the increase in new construction.

“So if property values rose due to new construction by 1 percent, that’s how much you can raise the levy by,” Stein said, adding that with inflation, that can be nearly impossible for municipalities.

Levy limits matter for debt because property taxes used to pay for a local government’s operating budget are constrained by the levy limit, but property taxes used to make payments toward debt are outside the levy limit.

“That gives you an incentive to borrow to make certain payments, because then (local officials) can raise the property tax by … as much as is needed to make that payment,” Stein said.

And in Wisconsin, property values have risen — making it easier for local governments to repay their debts.

For the state’s two largest cities — Milwaukee and Madison — property values play a key role in how they’re faring.

In Milwaukee, more of the city’s property tax levy is being put toward debt payments. Debt in the city’s 2023 budget would account for 31.7 percent of the overall levy — the most since 2008, according to the report.

Madison has also seen debt payments as a share of general-fund spending rise, but property values in the Capitol city are so high, the burden isn’t as onerous to the operating budget than it is in Milwaukee.

“Milwaukee would be a good example of a community that has higher debt levels,” Stein said. “Madison, on a per capita basis, has relatively high debt levels, but because the property values are high here — if you think about its debt as a share of property values — it’s much lower in the city.”

With interest rates on the rise, Stein said he’s interested to see how communities will fare, noting that federal assistance from pandemic aid and the infrastructure bill may help communities free up money to pay down debt.

“I do think there’s reason for some caution,” he said, “and to follow this pretty closely.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.