When you think about the psychedelic 1960s, images by Robert Crumb swirl around, somewhere, in the blacklight room of your mind.

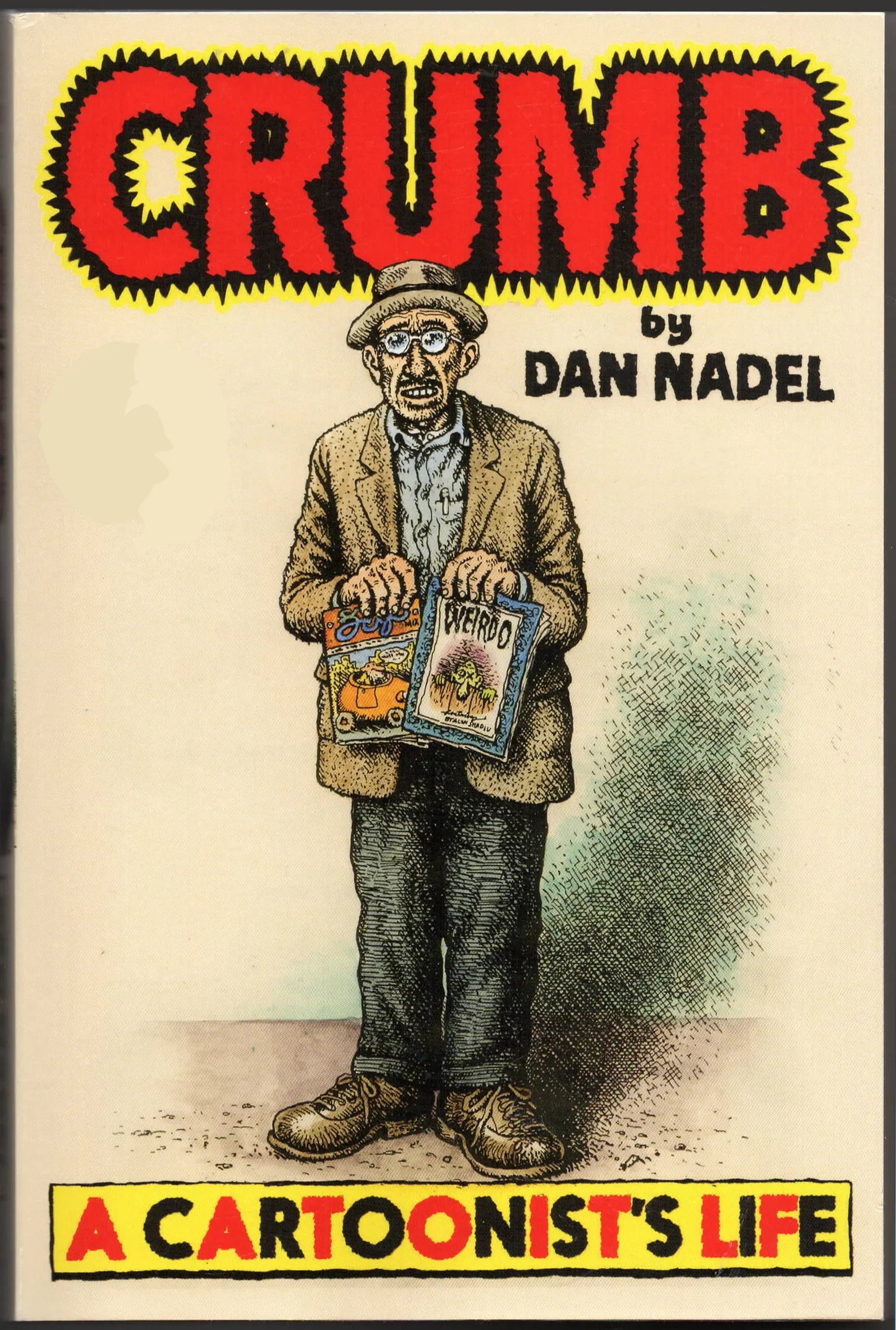

Until now, the only story of Crumb’s life is the documentary film “Crumb” by Terry Zwigoff. However, Dan Nadel has now written a biography, tracing Crumb’s life and work in “Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life.”

WPR’s “BETA” took some time away from rereading “Zap Comix” to chat with Nadel about Crumb and his controversial art.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Doug Gordon: How did you get the chance to write the very first biography of Robert Crumb?

Dan Nadel: In 2019, I wrote him a letter proposing this very idea, with the pitch being that I wanted to contextualize him in comics and the 20th century, that I wasn’t interested in unearthing personal revelations, although I did along the way. But my focus would be his legacy and where he comes from in terms of art history. And after some back and forth, he agreed.

But there were two things. One was that he wouldn’t have to explain comic book history to me, which was enormously appealing. He did not want to educate his biographer in his medium.

The condition he put on my writing the book was that I very honestly address the racist and misogynist material in his comics and give that a fair airing so that it would not be a hagiography. I, of course, agreed, and off we went.

DG: Robert and his brother, Charles, collaborated on writing their own comic books. What can you tell us about these comic books and how they influenced Robert’s artistic ambitions?

DN: They started collaborating in the early 1950s when they were not even 10 years old. And Charles had the idea and the charismatic leadership quality that meant Robert was under his sway. And so they would make these monthly comic books. They were just hand-drawn. This was before the advent of Xerox machines, of course. So they were just shown around their classrooms and amongst the family.

They drew advertisements. They drew subscription notices, all that kind of stuff, just for the sake of themselves. And they pumped these out monthly — fully 24 to 32 page comics every month for almost a decade. It was really something.

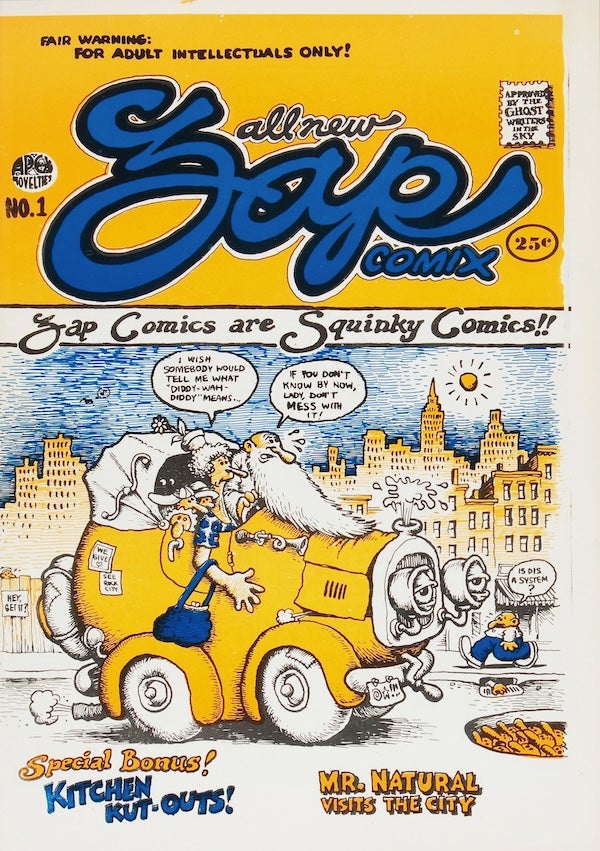

DG: In 1967, Crumb started drawing a monthly 24-page, 25-cent comic book called “Zap Comix.” Can you tell us about the cover of the original “Zap No. 1” and what you thought of it?

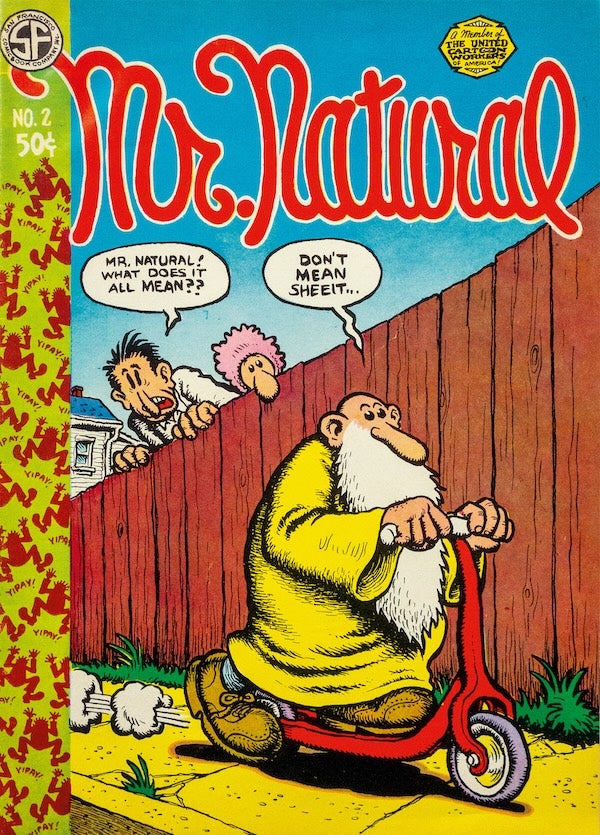

DN: The very first cover of Zap is this incredible vision of Mr. Natural and other characters stuffed into an old jalopy with balloon-like tires. It’s in front of a cityscape, and there are all these phrases on the cover that signal that this is not at all a normal comic book.

For example, in place of what had been the comic book code, which guaranteed that a comic book was appropriate for children, it says, “approved by the ghostwriters in the sky.” And at the very top of the cover, it says, “Fair warning: for adult intellectuals only!” It was telegraphing that this comic book was something else entirely — that while it looked like something, maybe from your childhood of the 1940s and 50s, something was not right inside of it.

DG: I’d like to get your opinion on Angelfood McSpade. Can you tell us about her and how she is possibly the most controversial comic character from the silver age of comics?

DN: Angelfood McSpade was a character that Robert invented that was based on a generic racial racist trope of the kind of wild, Black, jungle woman. And she was drawn as though she was made out of cylinders. So this cartoonish, cylindrical sexual fantasy of a Black woman was a character that Robert employed and did a few different things with.

On the one hand, he showed how she could be a stand-in for this objectification of powerful Black women in the culture. It’s like the way someone like Tina Turner was marketed as this unhinged savage or something horrible like that, the way a lot of Black music at that time was marketed as being somehow more authentic because it’s so wild and unhinged.

And on the other hand, he used her as a way to show how white people approached Black people in the culture.

He has a great strip that’s extremely difficult to look at, about a group of anthropologists and scientists going to find Angelfood McSpade in the deepest “jungles” and bringing her back, offering her fame and fortune, but then totally degrading her. It was his commentary on how white people have appropriated, used and then discarded Black people throughout the history of culture, particularly when he was writing and drawing this in ’67 and ’68. It was a particularly horrible history.

That said, he is also using an extremely disturbing racist caricature to do all of this. So while he’s commenting on it, it’s also, understandably, extremely difficult for many people to look at. And it’s the thing he’s critiquing in some ways, as it doesn’t transcend the racism inherent in its design or Robert’s gaze at it. It is a problematic work of art, but it is undoubtedly worth examining and thinking about because Robert is not racist; however, he did employ these sorts of images and was not always successful in telegraphing to anyone that this was not meant to harm.

DG: Would it be fair to say that there was a lot of controversy because people weren’t able to realize the nuances of what Crumb was telegraphing?

DN: You know, it’s interesting that at the time, there wasn’t controversy. That didn’t happen until decades later, really, until the 2000s.

DG: I’d like to ask you about a sketchbook comic strip called “Har Har” that Crumb created in 1966. Can you describe it for us?

DN: “Har Har” comics is a comic page from Robert’s sketchbook from 1966. It was a free-association comic, so he drew it directly in his sketchbook. It’s a series of seemingly unrelated events. It’s really like a surrealist, poetic narrative. And with that comic, he abandoned what he had been doing, which was a more linear, observational storytelling.

What came after were things like “Whiteman” or “City of the Future” or “Life Among the Constipated,” in which he is just basically thinking on the page and not trying to tell a character-based story, but rather move readers through moods and ideas and images without being burdened by getting from point A to point B in a plot.

That set the tone for the kind of wild, psychedelic, surreal comics for which he became extremely famous. And he worked in that mode until about 1974.

DG: One of my favorite Crumb works of art is “A Short History of America,” which is so un-Crumb-like. Can you tell us about it?

DN: Yeah, that’s a wonderful piece. “A Short History of America” was initially published in CoEvolution Quarterly in 1979, and it’s a series of panels that all take place in the same spot. It starts as a meadow, essentially. And then you watch this American place change over centuries.

So a railroad comes in, and a shack is built. Then there’s a road for cars, and then a little village around it, and then eventually a highway and a convenience store and a rat’s nest of electrical wiring and all that.

It’s very quiet and wordless, and it simply moves you through time, yet keeps you in one place. It’s a marvel to have come up with the idea of watching a place change over time in panels. It’s drawn with great restraint, and it’s become a work that stands in for Crumb. For many people, it’s something they cherish as a warning and a poignant reminder of how things can change over time.

DG: Given the frequently controversial nature of his work and the constant evolution of what is socially acceptable, what do you think Crumb’s legacy should be?

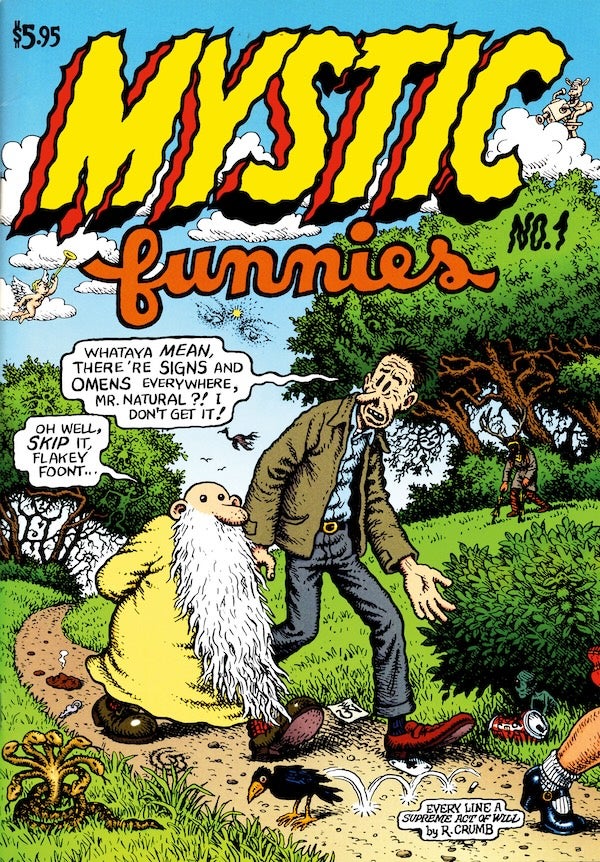

DN: I think it’s a complex legacy. I think he’s one of the great artists of the 20th century. He paved the way for an enormous amount of innovation in comics. He also, for many contemporary artists, opened them up to express their inner demons in a way that he and his compatriots did. And I think you can read his work, certainly the best of his work, and tap into a vision for how to think about America, how to think about contemporary life and how to deal with our inner selves — our lusts, our anger, our anxieties and our paranoias.

So, a complicated legacy, but a legacy of somebody who communicated through art and communicated, I think, vital information about how we might think about and move through the world.