In his sixth poetry collection, University of Wisconsin-Whitewater professor emeritus DeWitt Clinton writes from an emotional place — for the first time.

“The writing that I was doing prior to this collection had an objectivity to it,” Clinton told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “I hardly ever wrote about any feelings. I was always trying to observe without being emotional. For decades, I would write about something in the world through the lens of history or a specific text or a painting.”

But in his newest collection, “When & If,” Clinton’s topical throughline is the fear he experienced during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. And beneath it all, Clinton grieves the loss of his beloved wife of 48 years.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“These poems have helped me recognize that I do have emotions,” Clinton said. “I may not communicate them very well with people, but I’ve discovered them in me.”

His wife, Jacqueline, died in 2021, but not from COVID-19.

“The book is essentially a Kaddish, or a memorial, to all those who did die in the pandemic, as well as someone in my home who didn’t die of pandemic but from other illnesses,” Clinton said.

Clinton continues to grow as a person and an artist — although he might object to his poetry being called “art.”

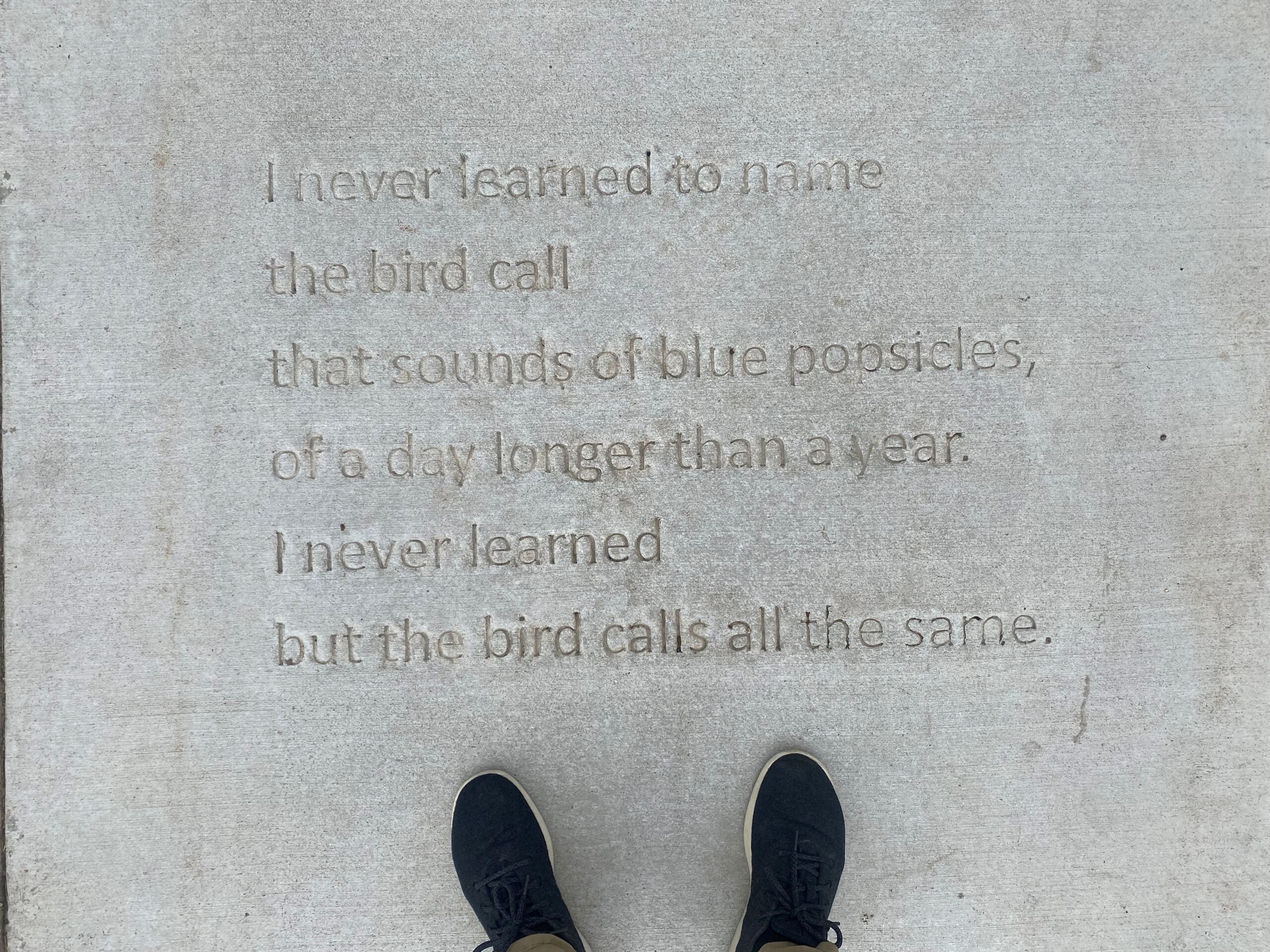

“The poems are spontaneous. They’re not crafted,” Clinton said. “Some readers might say, ‘Well, this isn’t really poetry.’ I wouldn’t argue with that reader at all about that. It’s something, and the closest thing to it is poetry.”

In his interview with “Wisconsin Today,” Clinton discussed his evolving feelings about the pandemic, his experience as a professor and the fresh, hopeful tone of the collection he’s currently writing.

The following was edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: This collection includes very few stanza breaks. Why did you compose in this format?

DeWitt Clinton: When you compose in stanzas or formal verse, which I don’t write in, you’re aware of making something artistic. I don’t think any of these poems are artistic. It’s more like spontaneous writing — not stopping until you have exhausted yourself, which is what a lot of the poems did for me. They just exhausted my mind.

I wanted to compose these so that a person could read them as a conversation. But I don’t think there’s any attempt on my part to make the piece that I’m writing artistic. It’s more of an outpouring of many emotions.

KAK: That might feel inspiring and refreshing to someone who’s like, “Well, DeWitt’s just letting words fly. I should try letting words fly onto the page, too.” What would you say to that?

DC: I would say, “Let’s do that together,” or, “Try that out and see how you feel.”

So much of poetry, when you read it in poetry journals or in books of poetry, you see carefully crafted work. I would be the first to say my work is not carefully crafted.

KAK: Do you still feel the same fears as you did when you first learned of COVID, before the first vaccine became available?

DC: I’m not as afraid of it as I was back in 2020 because of vaccinations and because federal health officials are telling us COVID rates have declined. But I think we will always have terrible outbreaks of diseases like this. But I’m not as afraid. I’m not writing so much about that now.

KAK: What are you writing about now?

DC: I’m writing a new collection called “ISWASIS,” which is confusing to people. Because there once was a present, and then it’s a past and then there’s something new. It’s looking back a little bit at life and into the future.

I think they’re more hopeful poems. At least, I would hope so. I’ve kept with that notion of writing poems as one stanza. But these aren’t experimental poems. These are poems of continued emotional responses to a variety of things. I haven’t found an exact theme that matches these poems.

KAK: I wonder if you ever tell yourself, “No more. I’m done writing about COVID. I’m going to focus on a different topic.” Do you do that at all? Do you compartmentalize topics?

DC: I can answer your question this way: I have taught Holocaust literature and genocide literature at my university for quite a long time. When I came up to a last sabbatical, I was proposing another study of genocide as it applies to literature. And then, in the application of the sabbatical, I said, “No, I don’t want to do that. I’d like to look at all the world collections of 100 Poems.”

There aren’t very many out there. There may be fewer than 100 collections, because it’s quite a challenge for a poet to put together 100 best. But I came across a Chinese translation of “One Hundred Poems from the Chinese” by Kenneth Rexroth and the first poem was so beautiful. These are poems from the eighth or ninth century through the 13th or 14th century. I started writing and I felt like I was under a waterfall, because it was so refreshing to me to be not writing or studying the horrors of the Holocaust and genocides everywhere.

So I’m sure that my meter will change over time. How, when, where and why? I have no idea. I’m always surprised at what the next day becomes. I’m trying to live in the present as much as possible, and it’s very hard because you’re always thinking about what you’ve done and what you’re going to be doing. So I look upon life as, “Oh! Oh!” — as a surprise.