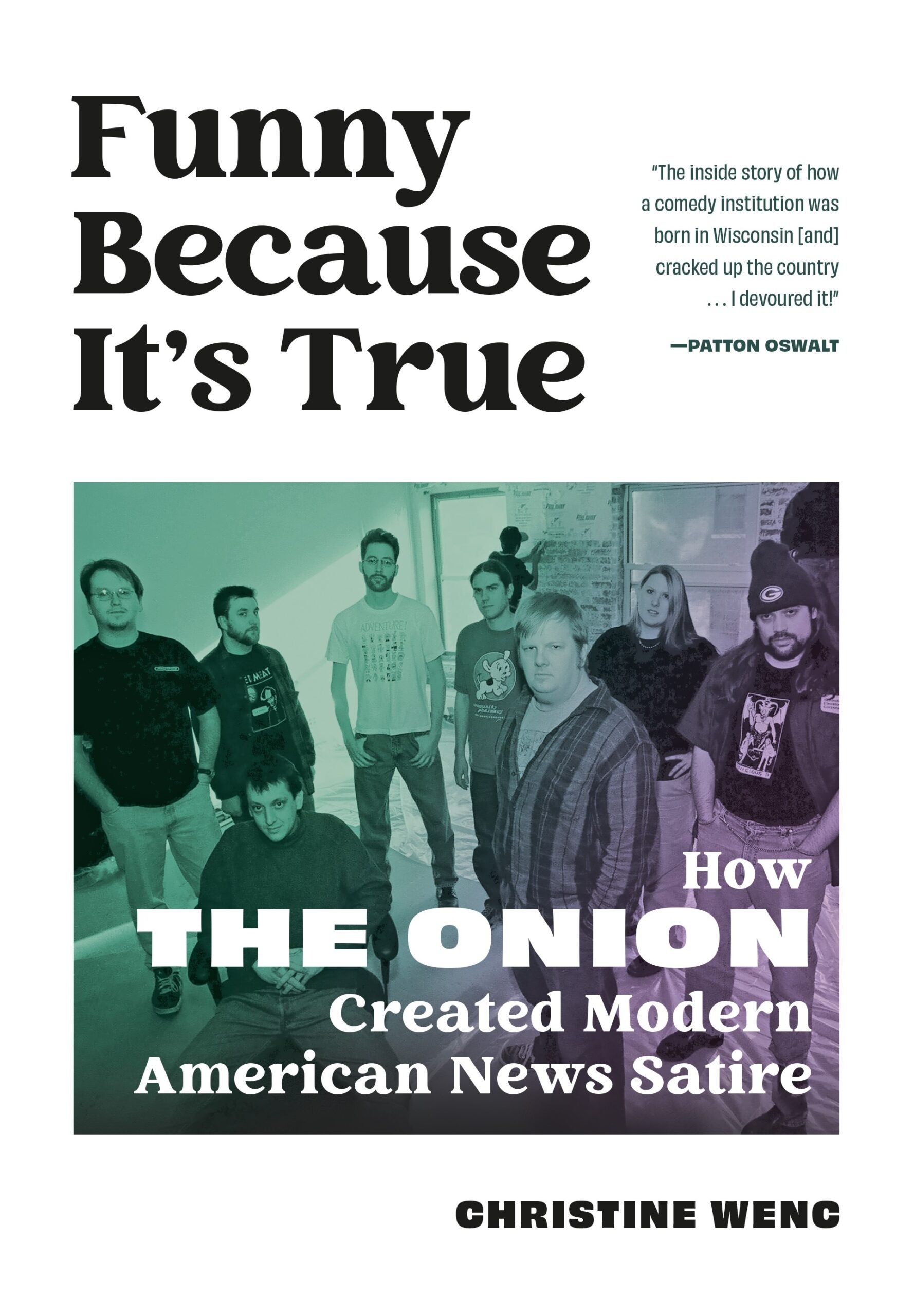

The Onion was founded in 1988 in Madison nearly 37 years ago. The paper featured satirical news stories and copious coupons that college students could use at local businesses.

Christine Wenc was there from the beginning and has just written a book on The Onion’s journey to national prominence called “Funny Because It’s True.”

WPR’s “BETA” wanted to learn how The Onion became “America’s Finest News Source,” as its tagline says. We asked Wenc to share some of her recollections from the book.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Doug Gordon: You were a member of the original staff of “America’s Finest News Source,” The Onion. What did you do?

Christine Wenc: My roommate started The Onion. I think I was 19 when Tim Keck told me he wanted to start a newspaper. Initially, he hired me as the art director, but I didn’t know what that was, so I became the copy editor. I did some illustrations and wrote a little stuff. But in the beginning, everybody did everything.

DG: Why did you decide to take on this herculean task of chronicling the history of The Onion?

CW: The book is the result of six years of research, writing and rewriting. I moved back to Madison from Boston in 2017 and was on the East Coast for about 25 years. So coming back to my college town, you naturally start thinking about what you did in college. I started thinking about The Onion.

It was also the beginning of a very intense conversation about fake news. So, that was on my mind, as well. I was interested in what happened with The Onion, but I also thought, “Wow, I wonder what The Onion people think of all of this stuff happening right now,” which drove me to do this project.

DG: How would you describe the signature Onion article?

CW: I could answer that question in a lot of different ways. The one I appreciated and where the book’s title comes from is the style of Onion article that’s just stating the facts. It can be silly, political or serious. There was one recently that made me laugh really hard in the new print edition: “Man so hungry he could eat an orange.”

My middle schooler heard me read that, and I just snorted laughing. He came over to see if I was OK. That’s an example of a silly one, but there are many classic political ones or social criticism ones that seemed to me to be stating facts, right? That’s an emblematic kind of Onion headline for sure.

DG: You’ve identified five primary reasons people think Onion stories are real. Could you share them with us?

CW: The first one is the story is in print. This probably affects older generations of people who are used to a time when print meant real. Print was something that was edited. It was fact-checked, and amateurs very obviously created anything that amateurs created. If you grew up with that, it’s easy to think it’s real just because it appears in print.

My second one is the story provides an answer to a deep need. One example is “New smokable nicotine sticks: Can they help smokers quit?” Which was published on July 22, 1998. After the story was published, people who were desperate to quit smoking called The Onion, asking where they could buy them. So when you really need something, you’re going to be inclined to believe something that fulfills that need, maybe that you wouldn’t otherwise.

No. 3, The Onion confirms a belief they already have. One example is, “Harry Potter books spark rise of satanism among children.” As I understand, the outcry about this was completely ludicrous and insane and ridiculous, right?

No. 4, the story taps into some deep irrational fear. This might include “‘98 homosexual-recruitment drive nearing goal,” published July 29, 1998. Editor Rob Siegel said it went up on a lot of anti-gay hate group sites, saying, “See, this is what they’re trying to do.”

Finally, the inability to discern multilayeredness or irony, which I also call the innocence defense, and I think we see a lot that connects to bad fake news.

DG: How did The Onion relocating to New York City affect it?

CW: When they moved there, they were trying to sell out during the dot-com boom, which collapsed spectacularly. It didn’t happen. So, they decided to move because they wanted to connect with their comedy peers. They wanted to be in a more prominent place. They’re sick of being in Madison.

The editorial office moved, not the business office. People were still in Madison and Chicago on the business and A.V. Club side. At this point, The Onion appeared in print in several different cities. The first print edition was going to be Sept. 16, 2001, which, for obvious reasons, didn’t happen. Instead, their first New York edition was the 9/11 edition, one of the absolute classics in Onion history.

DG: In 1996, The Onion started going digital and creating online videos like the Onion News Network, Onion SportsDome and, of course, we can’t forget The Onion’s parody of clickbait websites, ClickHole. What impact did that have on the writers and the audience numbers?

CW: When The Onion went online, it really exploded at that point. They had their voice down by that point. They had redesigned themselves into more of the straight-up USA Today parody that people who remember the newspaper will think of The Onion as being. It was more tabloid before that. So, they had figured out their satiric voice. They were fully formed.

Then they went online in ’96 when there wasn’t much in the way of comedy websites, and they just completely exploded. They became famous almost immediately in a matter of weeks, so it brought The Onion to everybody.

DG: I think Todd Hansen‘s satire description is the best description I’ve ever read. It’s, “Satire is telling the truth to power. Marketing and advertising is literally telling lies on behalf of power.”

CW: Yeah. That comes up in the book when I learned, to my shock and horror, that The Onion, in order to keep themselves going financially, started publishing sponsored content, which are known as advertorials. I was so shocked by that. I had to ask the person who told me to repeat it because I couldn’t believe what I was hearing.

At this point, they had corporate owners. They became one little unit, like in a private equity firm’s portfolio, like an object that was an investment to be traded and discarded when it wasn’t needed anymore. Luckily, that’s not happening anymore. That was probably one of the lowest periods in The Onion’s history.

DG: You argue that The Onion’s brand of satire is still valuable as a means of culture jamming. How so?

CW: There’s something about satire and comedy that can get to the point, and there’s so much spin and junk, and the whole news world is so completely fragmented. There’s still something in the way that humor can penetrate all that stuff and explode it all with one line. I think The Onion is important.

A lot of people are doing comedy online, and there are tons and tons of people who are good at it. But people still read The Onion even though it’s almost 40 years old. How can that be possible? They just got a million followers on Bluesky. Amazingly, people are still finding it relevant. They all are probably over 40, but at least there’s one middle schooler in my house who is now a big fan.