Growing up in Waukesha, Michelle Thaller can’t remember a time when she wasn’t obsessed with space.

Her mom says as soon as Thaller could talk, she was pointing at the stars and trying to go outside at night. She spent her childhood watching Carl Sagan and frequenting the Milwaukee Public Museum and the Yerkes Observatory.

To no one’s surprise, Thaller became an astrophysicist. Then, she met and married another astrophysicist, Andrew Booth. For 26 years, they were a space research power couple at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and Goddard Space Flight Center. Booth worked in quantum optics and interferometry. Thaller was a director of science communications, as well as a host and producer of space podcasts.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

And then in 2019, out of the blue, Booth was diagnosed with a rare form of brain cancer. He died less than a year later.

Thaller left NASA and disappeared for a while into the black hole of deep grief. But she never lost her connection to the cosmos.

She recently moved back to Wisconsin and spoke with Anne Strainchamps on “To the Best of Our Knowledge” about the solace she finds in astrophysics and in new theories about the nature of space and time.

The following was edited for brevity and clarity.

Anne Strainchamps: There’s an experience many of us have for the first time as kids: lying outdoors at night and looking up at the sky, with layer upon layer of stars stretching as far as you can see — like a window onto infinity or eternity. That’s how it strikes me. But how about for you, as an astrophysicist?

Michelle Thaller: Infinity is a slippery thing for me. Certainly, space seems to go on forever when you’re looking up at it. But we used to be little people who lived in caves and thought the forest or the ocean or the sky went on forever, when it’s just that we couldn’t see any farther.

We’re in the same position right now when it comes to the universe. We are absolutely certain that we have not seen to the edge of the universe yet. And so we don’t know whether it’s infinite or whether there’s some larger shape to the universe or to space and time. Could there be other universes out there? We just don’t know.

AS: You have written so movingly about how this perspective on the universe, the perspective of an astrophysicist, helped you survive deep grief after your husband died. It’s also something the two of you discussed frequently during your last year together?

MT: Absolutely. More than a hundred years ago, Albert Einstein and a number of other physicists really did take seriously the idea that space and time are the same thing. They really thought that if you had the right perspective — probably not in our own three dimensions — you would in fact see all of time as a whole thing. And so [when we got the diagnosis], Andrew and I took a deep breath and said, “We’re not really leaving each other. I’m going to have to go on alone now. But when the universe began, I was holding your hand. And when the universe ends, I’ll still be holding your hand.”

Einstein wrote a letter to his best friend’s widow after his friend died in which he said this person is still with us, every bit as alive as he was. In the landscape of time, he’s just over the hill from us now. We can’t see him, but he’s still there. Andrew and I kept that idea with us as we made that journey.

AS: What was Andrew like? The two of you shared a profession, and so concepts like spacetime or quantum entanglement, which seem so counterintuitive to the rest of us, were very real for the two of you.

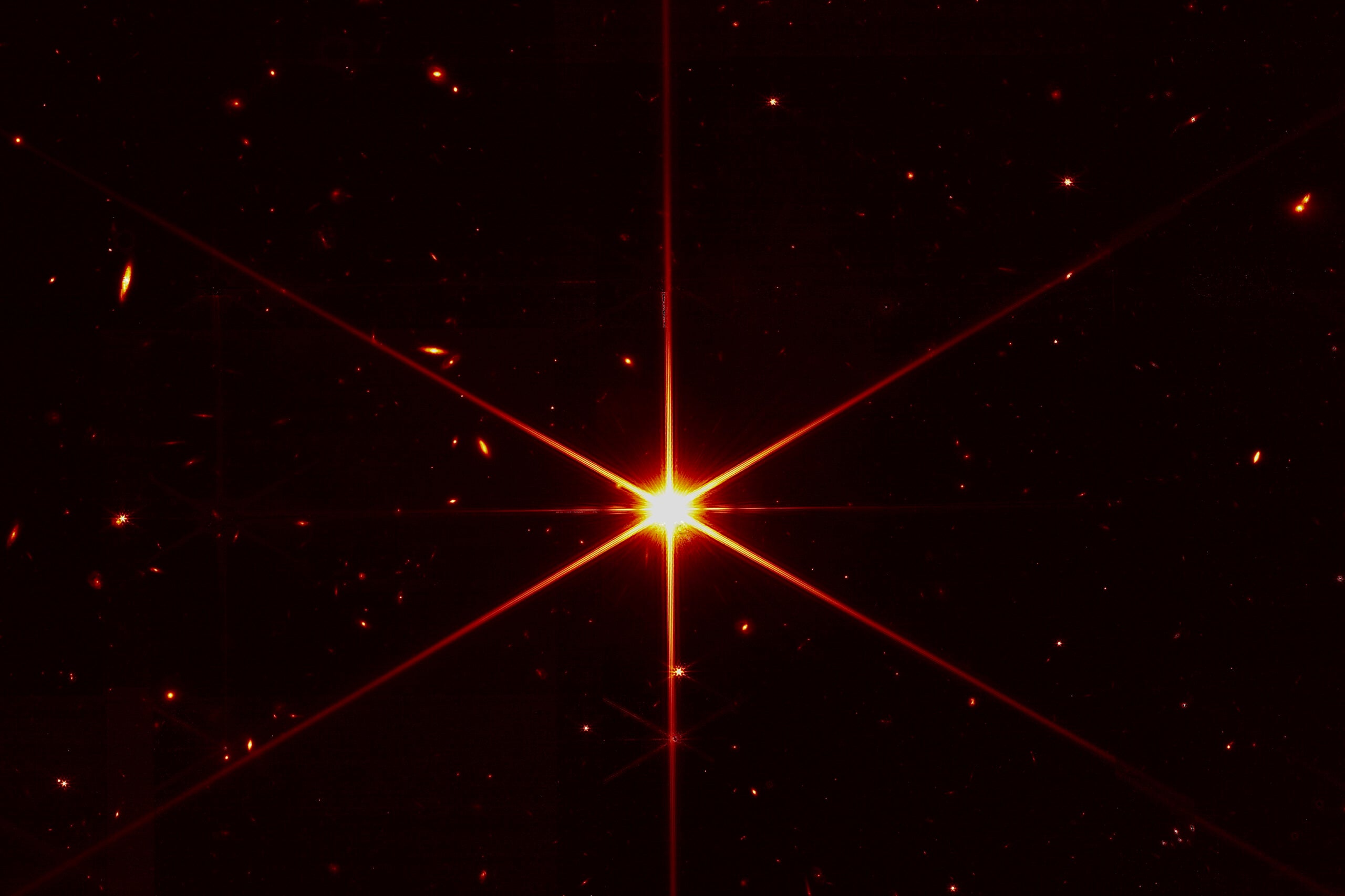

MT: Andrew was this brilliant man at NASA, but he was also joyful and humble and friendly. He was always playing Dungeons & Dragons games, and we loved dressing up as wizards. He was a quantum optics person who did interferometry, a technique for building a telescope that only works if reality is stranger than we know. It’s how they made pictures of the giant black hole, by linking telescopes all around the world to act as one single telescope. In order to work, they have to be set so accurately that the same particle of light appears in all eight telescopes at once.

“We’re entangled not just in space but also in time.”

Michelle Thaller

AS: And not as a single particle in one spot, right? You’re talking about a particle appearing simultaneously in eight different places. How is that even possible?

MT: Some people think it’s something called quantum entanglement. We do this experimentally all the time in laboratories all over the Earth. China even did it up to their space station and back. You take two particles that were once close together, move them apart, and even if they’re separated by a billion light years, somehow they remember each other. They adjust simultaneously. That’s because the universe doesn’t really care about what we call space and time; it’s not an intrinsic property of the universe. And so now we wonder if maybe spacetime itself is made of these entanglements. Maybe we’re entangled to everything in the universe.

AS: So maybe you and Andrew are still entangled?

MT: Oh, absolutely. There’s no way we couldn’t be, after spending so much time in proximity, sharing so many molecules. We’re entangled not just in space but also in time. That doesn’t help so much with the human, psychological aspect of grief, but it’s a way of letting go and saying that we don’t even understand what reality is yet.

I don’t expect to find another version of Andrew in an afterlife, but we had this time together and that spacetime always exists. It’s there. And so you have to ask, are we actually eternal?

AS: He’s gone from your living room and from the pillow next to you, but from an astrophysics perspective, he’s not really gone from you.

MT: Yeah, what if everything you experience — all of the good things, all the frightening things, all the days you want to live forever, all the days you’d rather not be alive — what if it’s all happening at once? That’s what Einstein thought the universe was like.

AS: I know you said that doesn’t necessarily help with the actual experience of grief, of having your life break apart and having to construct a new life, but I would think it might help.

MT: The thing that shocked me about grief — and nobody told me about this — is that I love to read, but for about three years after Andrew died, I couldn’t read a book. My brain would just slide off the words. I had the privilege of being able to afford to go to a grief counselor, and she would say, “This is very common. Your brain is processing stuff and trying to rewire how you live.”

Because she knew I was a scientist, she showed me MRI pictures of people before and after grief, and there had been actual physical changes in the brain. And she said, “Every habit, every plan you’ve had, is out the window. That means you’re not going to be able to concentrate as much. You’re not going to be able to read. At work, you may find it difficult in meetings to pay attention.” I hadn’t realized all these concrete effects in the brain that grief has.

But I do like to think of time as something we don’t understand completely yet. Is time infinite, or does it have a beginning and an end? We don’t know. And so I wonder, are we part of an eternal structure that we’re not really aware of?