In April, Wisconsin’s Keith Bechtol was in the remote Andes mountains of Chile waiting for the world’s largest digital camera to turn on and take a photo of the night sky.

“I was very focused to the task at hand,” he told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “I was selecting the target that we would use for the very first images.”

Since 2016, he’d been working with thousands of people around the world to launch the Vera C. Rubin Observatory — an idea that was initially sketched on a napkin 27 years ago. Scientists say this telescope will give a look of the cosmos never seen before. The images it captures are 3.2 billion pixels and cover a wide region of the sky, about 45 times the size of the full moon. To display a single image at full resolution you would need to cover a basketball court with high definition TVs.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Bechtol, an associate professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, designated what part of the sky to photograph. After some anticipated tinkering, the team anxiously waited for the images to appear.

When the images slowly came into focus, the room of researchers fell quiet.

“We’re basically seeing the light from galaxies before the sun and the Earth formed in our solar system,” he said.

Those initial images, which were released to the public in June, showed in great detail the Virgo Cluster, the closest galaxy cluster to the Milky Way. It also showed the breadth of cosmic history.

The conductor

Bechtol is the system verification and validation scientist for the project, which he plays a major role in. He is simultaneously an engineer and a physicist helping gather the evidence that the camera, the telescope and the data management system are all working on together.

He compared it to a conductor who ensures all the instruments in an orchestra are playing harmoniously.

Bechtol said the purpose of the telescope is to capture multiple images of the night sky over time and view how it changes. It will take digital exposures of the night sky every 40 seconds for the next 10 years. That will be about 800 to 1,000 images each night and 2.5 million images over the decade. This project is called the Legacy Survey of Space and Time.

“What that allows us to do is bring the night sky to life in the sense that we see everything that moves,” he said. “We see everything that changes. We can see asteroids moving throughout our solar system. We can see stars pulsating throughout the Milky Way. We can see stars exploding in other galaxies.”

It’s the greatest cosmic movie of all time, he said.

Answering the big questions

The information from the telescope, which will be available to scientists across the globe, could answer questions people have been asking throughout human history. How have galaxies evolved over more than 10 billion years? How did the universe begin?

The project will give scientists a lot more data to work with. Bechtol said about 500 petabytes of data will be generated. That’s similar to all written language in all languages over all of human history.

The telescope and data could also advance research in Bechtol’s area of interest, dark matter. The telescope is named after Vera C. Rubin, the famed astronomer whose work provided convincing evidence for the existence of unseen dark matter in the universe.

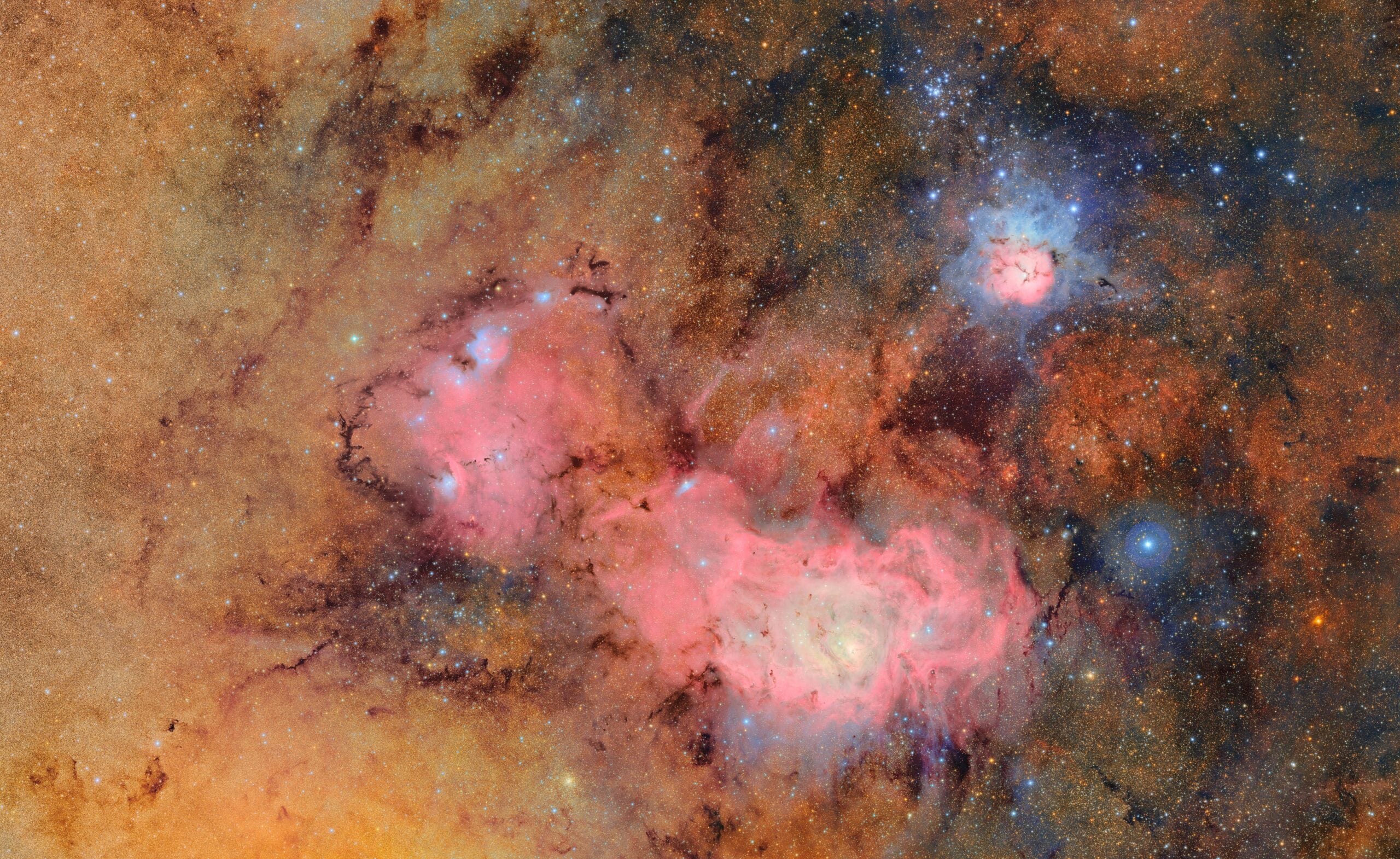

For now, Bechtol is spending many nights at his home in Wisconsin watching the data and systems, remotely ensuring everything is working as it should. And during those sleepless nights, he still reminisces on the initial images the telescope captured of the Trifid and Lagoon Nebula.

What you really see in Rubin images is the sheer number of stars, he said. The telescope brings out the colors that reflect regions where new stars are being formed, where the light from the stars is reflecting off of gas and dust in our Milky Way. He said what was striking was the amount of detail in the dust lanes and the range of colors.

“This is a region that we picked specifically because it’s so beautiful,” he said.