For years, Ahna Skop didn’t feel like she fit the mold of a scientist.

She comes from a family of artists. Her father, Michael Skop, was a pupil of a famous Croatian artist, Ivan Meštrović, and her dad brought in students from all over the world to an art school they had at their house. Her mother, Kathleen Prince Skop, is a ceramicist and retired high school art teacher.

“Here I am as a scientist,” said the geneticist and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “You might assume that I inherited the recessive gene for science.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In science, Skop entered a male-dominated field.

She has dyslexia and a genetic disease that brings her chronic pain. She’s open about the barriers she faces, so her students can see her as a real person.

While she was getting her doctorate in cell and molecular biology at UW-Madison, she remembers one bad grade in particular. It was a “low point in my career.” She had enough failures that she questioned if she belonged in science after all.

Skop recalls the moment when John White, who invented the laser-scanning confocal microscope, told Skop about a D he got in math once. Her anxiety around testing didn’t define who she could be professionally, she realized.

“That was the first time in my life I heard someone that famous just turn to me and say, ‘You know, that class didn’t matter, and I was able to do this remarkable thing,’” she said. “Just that one statement … changed the course of my life forever.”

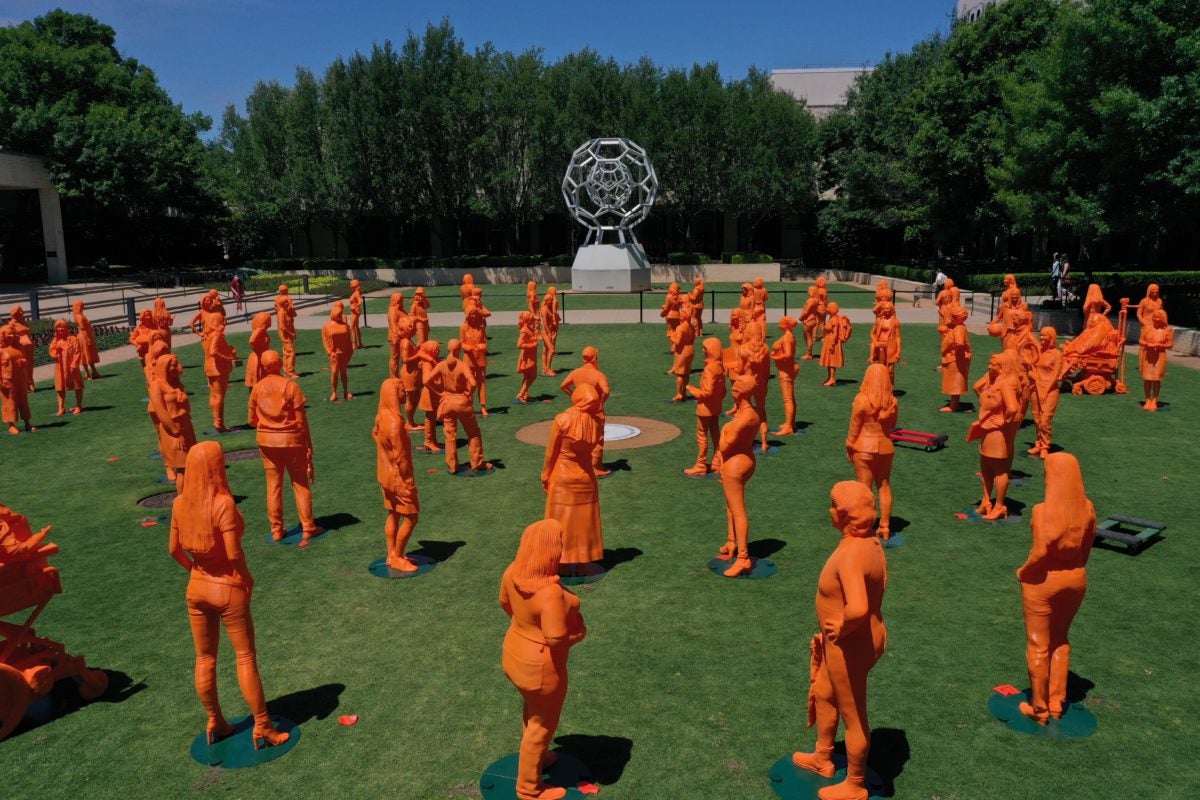

Last month, Skop’s likeness was one of 120 3D-printed life-size orange figures on the National Mall in Washington to celebrate Women’s History Month. The Smithsonian on Twitter called it “the largest collection of statues of women ever assembled.”

Skop joined WPR’s “The Morning Show” recently to discuss her background, her teaching style, breaking the mold and how she finds art in genetics.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Kate Archer Kent: How did it feel to be one of those 120 American women scientists who had a statue?

Ahna Skop: Well, it’s quite intimidating and thrilling at the same time to be 3D printed and out there as a sculpture. But I’m quite honored, and it has been remarkable to meet so many amazing other women scientists doing unbelievably awesome stuff. So, it has been very cool to be part of this program.

KAK: What was it like being 3D printed?

AS: I walked into a booth that is like a bigger suntan booth or something. And there are a lot of lights up around the edge, and they had almost like a “Project Runway” salon next to this. It was kind of fun, a different thing than (what) I normally experience. Then we had our hair and makeup done, and we went in this booth and then a bunch of lights went off. It scanned our body in three dimensions, and it was very intimidating because nothing is hidden in this capture of ourselves.

KAK: Some students find science and math intimidating. How do you approach that?

AS: The classes they took in high school, they realize they have to memorize everything. But really, that’s not what science is about. We know things, but we’re problem solvers, which is super fun.

Science can be intimidating because people think about all these other things and how those exams may have been to memorize things. But I think the way science is being taught now is changing because we’re doing this project-based learning in the classroom. That’s where the fun is. And that’s what I like about science because I study how cells divide, which is important — when it goes wrong, that’s what happens in cancer. So, I want to figure that out and be a problem solver.

KAK: Can you explain your grading system?

AS: I realized that (with) a lot of students, particularly women and underrepresented students, there’s often anxiety in the classroom. And it dawned on me that in the end, grades don’t matter. It’s what you get out of that course. So why not flip this idea: Instead of students working up toward 100 points — and most people know how to do all the math about losing points out of 100 — why not give them all the points on the first day, and everyone gets an A. The goal is to try to maintain all those points. But I give them about 800 points because … you don’t really know how many points that you’ve lost.

There are lots of students on the first day (who say), “I’ve never felt more confident on a first day of class than I did in yours.” And I think that’s why I use this unique strategy. I want them to feel welcome and have the ability to succeed, right? The point is not to tear people down. It’s to build people up. And I think that growth mindset theory that that is based on helps students understand that their point of view and what they bring to the table is important. It also levels the playing field because a lot of students have biases about where they are in the classroom.

KAK: How has having dyslexia and being a visual learner shaped how you relate to students?

AS: If you tell your students who you are on the first day, it allows them to see you in a different light — that you’re actually a real person behind there. You’re not this untouchable scientist. Students (say), “I never met a scientist who admitted in public that they were dyslexic.” I said, “My parents told me (Albert) Einstein was dyslexic.” Lots of famous scientists actually were. You realize that dyslexia is a gift.

KAK: Let’s talk about your passion for cell mitosis. You call it “nature painting itself.” What do you see?

AS: When I first saw the process of mitosis … coming from a background of (an) artist, I was completely gobsmacked (about) how beautiful this process was. And then when I started to ask about it, there’s a lot known, but there’s still a lot we don’t know about the process. Coming from a family of artists and seeing something so beautiful and to be able to then ask the question: How does that work? I really appreciate the beauty in science. If it wasn’t beautiful, I probably wouldn’t study it.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.