Actor Jeff Daniels talks about his audio memoir, ‘Alive and Well Enough.’ Also, film critic Matt Singer on how Siskel and Ebert reinvented film criticism. And rock critic Rob Harvilla gives us the lowdown on “60 Songs that Explain the ’90s.”

Featured in this Show

-

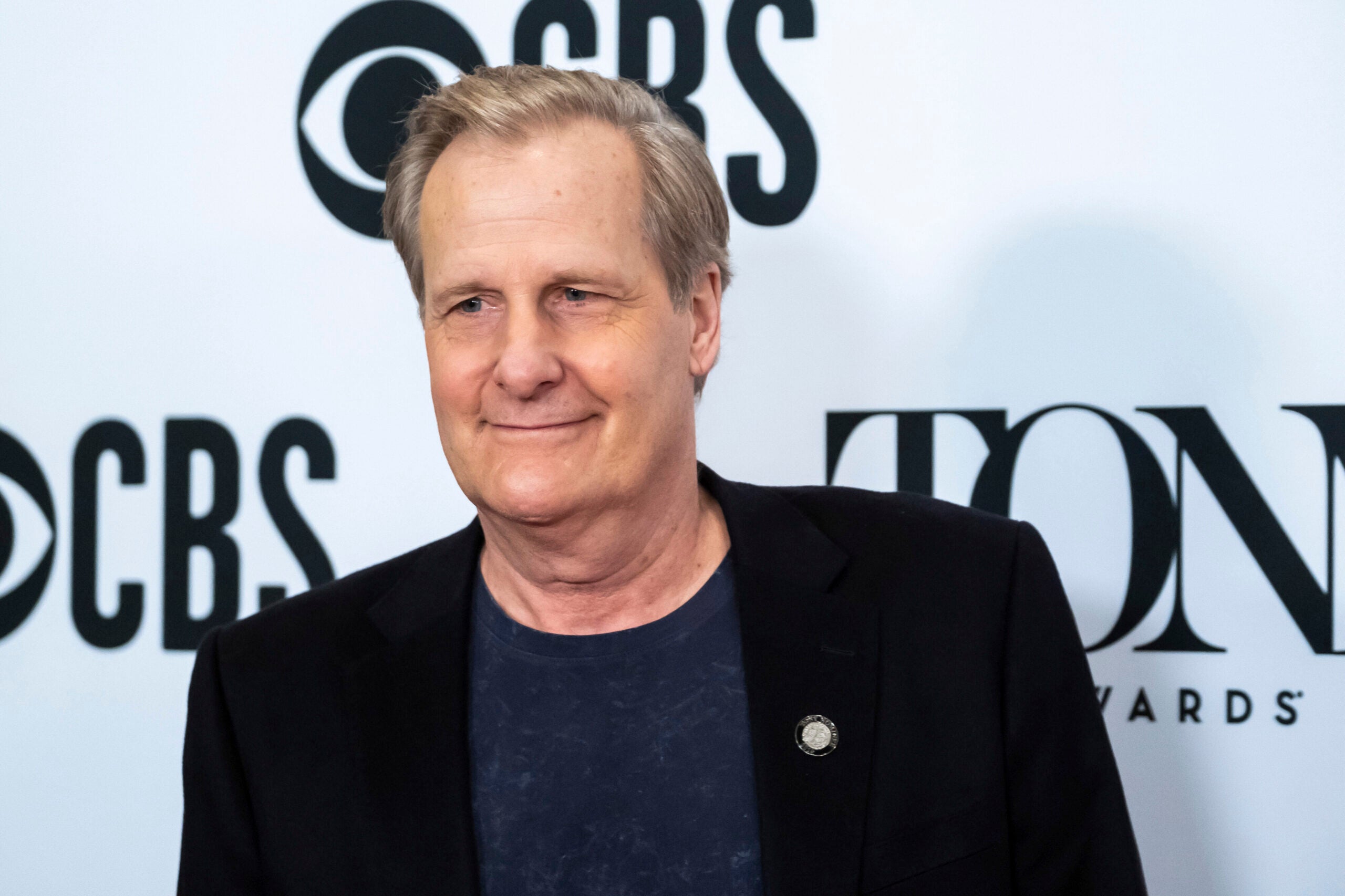

Jeff Daniels is 'Alive and Well Enough'

There is a place where one can share their accomplishments with the world from the comfort of their warm Midwestern home. One can sing songs, tell stories and recount tales of a life well lived.

It’s known as the podcast. And actor Jeff Daniels has one of his own called “Alive and Well Enough,” distributed by Audible.

WPR’s “BETA” spent some time talking with Daniels about the podcast and the rich life experience from which he draws his material.

Initially, Daniels felt like there were enough podcasts out in the world, and the last thing anyone needed was another one. But his agent talked him into it, and Daniels found “Alive and Well Enough” an excellent way to share his vast performance skills.

“It became this kind of one-man audio adventure that included how I got started, what acting is for me and what songwriting is to me. It just became this grab bag of everything I do and can throw into it, and I’m thrilled that people are responding to it,” he said.

Bringing theater to Michigan

In the 1970s, Daniels performed in numerous plays on and off Broadway. In 1980, he appeared in the films “Ragtime” and “Terms of Endearment,” and in 1985, he starred along with Mia Farrow in Woody Allen’s “The Purple Rose of Cairo.”

But Jeff Daniels might best be known for his role in the movie “Dumb and Dumber” and also for his role as news anchor Will McAvoy in HBO’s “Newsroom.”

In 1986, Daniels decided to move to his hometown of Chelsea, Michigan, and in 1991, he opened the Purple Rose Theater Company, named after “The Purple Rose of Cairo.”

“I was in New York for 10 years. The movies started to happen, and we could live anywhere. I knew I could pull this living in the Midwest and still being in the movie business. But after a few years, creatively, I was going to sleep,” Daniels said. “I remembered my days at Circle Repertory Company in New York City off-Broadway, where I started. And I wanted to create my version, which included living, breathing, playwrights, walking around the green room, and rewriting a second act.”

“I wanted to see if I could drop a professional theater company that I envisioned acting with a medium close-up film acting style on stage in front of 170 seats. See if I could create that with the people that were still around (Michigan). And 32 years later, we’re still here.”

One reason Daniels created the Purple Rose Theater Company was to attract audiences that had never thought live theater performances were for them. That was until the success of a comedy Daniels wrote called “Escanaba In The Moonlight.”

“I had done ‘Dumb and Dumber,’” Daniels recalls, “and we knew 12-year-old boys would flock to it. It would be their Citizen Kane. But when the demographic came in from 8 to 80, it was like, ‘How do I get those people into my theater?’ Theater is always viewed as elitist.”

“It’s just the great unwashed never bothered to go and, in some cases, shouldn’t. I mean, why bother? And I said, ‘How do I reach them?’ So I came up with an idea to write a play set in the Midwest, about five guys in a deer camp in the Upper Peninsula. And I included a 10-minute flatulence joke that riveled old Mel Brooks and Blazing Saddles, and we had people flocking to the theater. We had groups of 12, all wearing their hunting gear, orange vests, and hunting licenses pinned to their backs. I mean, it just became like a little ‘Rocky Horror Picture Show‘ thing.”

Bringing characters from movies to podcast

“Alive and Well Enough” allows Daniels to draw on his years as a performer, sing original songs, share experiences and highlight milestones from his vast performing career. In one episode, Daniels recreates a scene from “Escanaba in the Moonlight,” playing all five characters simultaneously.

But Daniels makes sure to include something for fans of all of his best-known performances.

“Well, I knew I had to get ‘Dumb and Dumber’ in there and attract those fans because there are a lot of them,” Daniels said. “I needed to get that into the podcast somehow. And I came up with the idea that Harry Dunn from ‘Dumb and Dumber’ would have his own interview show, and he was going to call it ‘Snack Time with Harry Dunn,’ where Harry this week would be interviewing the actor who played him in the movie, Jeff Daniels.”

-

Reopening the balcony: A look at the legacy of 'Siskel & Ebert'

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, you’d be hard-pressed to find a bigger rivalry between two competing newspaper identities than the one between the respective film critics of the Chicago Sun Times’ Roger Ebert and Chicago Tribune’s Gene Siskel.

“They had an epic rivalry through that time,” author Matt Singer tells Wisconsin Public Radio’s “BETA” of the two.

“Roger would talk about how they would be attending all the same press screenings in Chicago, and they would see each other at functions or events, and they would just not look at each other, and they would not talk to each other,” Singer continues. “If they were waiting for an elevator together, they would stand awkwardly in silence because they both knew that their jobs were to beat the other guy in print, write the best reviews and get the best access and interviews with stars and directors and all of that. So yes, they were very familiar with each other, but definitely did not like each other.”

Singer is the author of “Opposable Thumbs: How Siskel & Ebert Changed Movies Forever,” which traces how the two channeled this competitive energy into one of the most successful and groundbreaking syndicated shows in TV history and how Siskel and Ebert became movie-making power brokers.

All of that came from humble beginnings. In 1975, Chicago public television station WTTW pushed to have the critics join forces for a pilot episode of a show called, “Opening Soon…at a Theater Near You.”

Even Siskel and Ebert — who clashed on everything including physical appearance, hairstyles and eyewear — agreed it was a mess.

“It went very badly in almost every way. If you are a fan of the show like I am,” Singer said, “you might be astonished by how badly it went, given how good they became as this wonderful, charismatic, funny, insightful screen duo.”

Things would’ve ended there had it not been for a new WTTW staffer, Thea Flaum. She wisely identified that both the format and the conflicting hosts had a lot of untapped potential.

“They always credited her as being the one who figured out how to take this off-camera competition, rivalry, animosity and figure out a way to turn that into something that worked on camera,” said Singer.

Siskel and Ebert set aside their differences and worked diligently to get the show to work. They spent weekends at Flaum’s house, getting comfortable to be on camera and in the setting together.

“They did get better and more comfortable, and they figured out ways to bring that connection, or anti-connection, that they had off camera to make that something that worked for television,” Singer said.

The results were undeniable. While the show changed titles and stations over the years before settling simply on “Siskel and Ebert,” the secret sauce to their success remained the same.

It was more engaging to watch two passionate film fans and critics discuss the why of a film than to simply read a single newspaper column.

For the decades to come, Siskel and Ebert perched themselves weekly in the balcony of a Chicago theater where they argued — and sometimes agreed — on movies. The show was then syndicated, and they became household names and trusted tastemakers to viewers across the country. They rated each movie with their signature thumbs up or down and signed off their telecast with another signature line: “The balcony is closed.”

That success became evident in the early 80s when the duo discovered their dynamic might be well-suited for another outlet. They became popular and sought after recurring guests on the late-night talk show circuit.

“The show began to do pretty well on PBS. And that was when they started becoming really full-blown TV stars. They were, you know, in their heyday — they were as famous as a lot of the people in the movies they were reviewing,” said Singer.

Singer recounts a specific outing on the “Late Night with David Letterman” show where the two men simply refused to go off-brand.

“They were essentially kind of set up by producers,” Singer said. “They were both told to be prepared to tell this specific story. A funny anecdote about them jointly interviewing Jack Lemmon… And when Letterman kind of prompts it because they both want to tell the story, neither will let the other tell it, and it becomes this huge, genuine shouting match. They are really angry and annoyed and frustrated.”

Siskel and Ebert left the taping feeling a little embarrassed about arguing so vehemently on live TV, but learned a valuable lesson.

“As they were leaving the Ed Sullivan Theater, a producer on the show said to them, ‘That was a great segment, that was great TV.’ And that kind of summed it up,” Singer said.

For his research, Singer dove into the ocean of archived content available online of all the various Siskel and Ebert appearances, shows and reviews and identified nuances in their disagreements and categories of their fights.

“You watch hundreds of episodes, you start to see that they had different sorts of fights about different sorts of things. And amusingly, they could fight about a movie they theoretically agreed about. They could give a movie two thumbs up and spend the entire review fighting about why it was good, why they liked it,” he said.

Singer said the opposite was also true. They could both hate a film, but then argue as to why.

Take for instance, their disagreement on a forgettable 90s sequel “3 Ninjas Kick Back,” which spiraled into a much larger discussion on film in general.

“Gene (Siskel) would be like, ‘A good movie is a good movie, is a good movie. And this kids movie is not a good movie. Thumbs down.’ And Roger might look at it and say, ‘Well, these things are relative and relative to the standards of children’s entertainment. Thumbs up. Or perhaps I’ll give it a thumbs down. But I will tell you that I do think that it works on the level that a kid might enjoy it,’” Singer said.

“Then they would fight about that,” he continues. “Where they’re not even really arguing about the specific movie. They’ve used this movie as a jumping off point to a kind of higher-level discussion of what makes a movie good, what makes a movie bad? How do we determine that? Is it good if it appeals to every audience or is it good if it appeals to its target audience?”

Singer writes in “Opposable Thumbs” that even though they were predominately defined by their differences and debates, they never crossed a line personally and professionally that would end their relationship.

In fact, he notes that if wasn’t for Siskel’s death in 1999 after a battle with a brain tumor, the pair would’ve continued on debating films for the foreseeable future.

Even though Roger Ebert would continue the show in a similar format with a rotating cast of fellow critics and film directors for several years after Gene’s death, nothing held up to the magic of “Siskel and Ebert.”

Singer said the duo’s legacy expands well beyond just a thumbs up or down. Siskel and Ebert inspired a generation of arts and pop culture critics, launched or halted more than one or two Hollywood careers and pioneered a reliable TV format that is, for better or worse, still humming today.

“Certainly, there’s movies that they championed that they helped get out into the world and find an audience. Filmmakers they championed, that they helped establish careers,” Singer said. “I do think that even though there is not a ‘Siskel and Ebert’ type show on the air right now, at least about movies, I think that it has this enormous legacy and there’s lots of other shows we can think of on television now that are not about movies, but that have that same spirit and energy of people passionately arguing about something, you know, sports, politics, whatever it is that that model has become enormously successful in other worlds.”

-

Rob Harvilla breaks down '60 Songs That Explain the '90s'

Remember the music of the 1990s? Rob Harvilla certainly does.

He’s been a professional rock critic for more than 20 years. He’s the host of “The Ringer” podcast and author of the new companion book called “60 Songs That Explain the ’90s.“

Harvilla said his book “combines shrewd musical analysis, vital cultural and historical context and whimsical personal digressions.”

We at WPR’s “BETA” have got to say, Harvilla’s “whimsical personal digressions” are among many highlights of his book.

As frequent “BETA” guest Chuck Klosterman said: Harvilla’s book is “an increasingly rare thing: a book about pop music that’s legitimately funny.”

Harvilla serves up a smorgasbord of scintillating songs from a wide selection of genres, including grunge, hip-hop, R&B and ska punk.

Just like in his podcast, Rob shows how a single song could capture so much about the ’90’s era, whether it was Salt-N-Pepa’s takes on sex, Green Day’s example of selling out or The Counting Crows’ softening of the grunge era.

As a music-obsessed teenager during the ’90s, Harvilla said this project is also very personal.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Selling out is so ’90s

Doug Gordon: Chuck Klosterman gave you that nice blurb on the front cover of your book. He wrote a whole book on the ‘90s, and he described the one characteristic of the decade as the desire not to sell out. You have a whole chapter on bands facing this dilemma. Which song or band do you think best represents this struggle?

Rob Harvilla: Probably if you’re going for one song, one band, that’s got to be Green Day, right? They grew up in the Bay Area as part of this fiercely independent Bay Area punk scene —you know, 924 Gilman (Street), this mythic venue. You cannot play Gilman if you’re on a major label. And they signed to a major label, and they are like ex-communicated from Gilman, you know, they really anger people.

And people write all kinds of angry letters to the editor, angry reviews like … “Maximum RocknRoll,” who had loved them previously. It is totally turned on them and it hurts them.

“Dookie” sold like 10 million — I think maybe even closer to 20 million now — records. But they’re heartbroken at having lost the community that they started out in, that they grew up in.

And I think that’s the starkest example of people being so upset with the band for the crime of signing to a label that could better distribute their music. I understand the dilemma there. And I understand the argument of the purity of an independent label, but it is an idea that just does not make any sense.

The reason it is such a ’90s concept is that it basically did not survive the ’90s. This idea of selling out, it’s just not a thing people agonize about at all anymore.

Eavesdropping on Ice Cube

DG: Selling out seems quaint nowadays, but even in the ’90s, it was a little bit different for hip-hop acts. How so?

RH: I’ve been doing this podcast show for three years. Each episode is one song. And so when it comes time to write a book, I have to radically distill 600,000 words of raw material into a coherent book. And so when I think about doing a sell-out chapter, I’m trying to think about different ways to define that term. And in the case of Coolio or Ice Cube, the struggle they’re having is that suddenly they’re huge in the suburbs. Suddenly they have this huge white audience that has no experience with South Central L.A.

And I think it was Ice Cube who said, ‘White kids are eavesdropping on my music. Like, it’s fine if they listen to it. I’m glad they enjoy it. I’m certainly glad they buy it. But I’m making music for Black people and white people are eavesdropping on me.’

And I think Coolio is the same way. Coolio came up in a far more independent scene in Los Angeles, but suddenly he’s a household name, right? Suddenly “The Fantastic Voyage” is everywhere and everybody knows the braids, and “Weird Al” (Yankovic) is doing a parody of him (“Amish Paradise”) that caused the whole kerfuffle.

And he’s agonizing over the fact that this isn’t the audience that I sought, you know, like, this isn’t who I thought I was talking to. And he is honestly very concerned that he’s being viewed as a caricature and he has to sort of push against that. It just fascinated me the different ways that you could take that idea of selling out.

Erykah Badu is Harvilla’s vote for best live performer

DG: Erykah Badu gets your vote for the best live performer of her generation. Why?

RH: I’ve told this story on the podcast many times, and I’ll keep telling it because I saw her live in the early 2000s at the Newport in Columbus, Ohio. My first job was at an alt-weekly there as an arts writer and arts editor.

It was a fantastic show, and she had a giant Afro and at a climactic point in a song, she picked up the Afro off her head and bounced it on the stage, just like ‘boing’ — like it bounced across the stage. And it was the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen at a rock concert. And I’ve attended probably closing in on 1,000. She is just so fascinating, it’s so magnetic. I saw her at Radio City Music Hall. I saw her at smaller places. I just hung on her every word, to a degree that I can’t say about any other performer. I don’t know what it is exactly, but she’s incredible.

DG: Do you have a favorite song from her live album that really kind of speaks to you?

RH: Oh, dude, it’s got to be “Tyrone,” right? I mean, when I did an episode on her, that’s the song I did an episode on. She put out her debut album in 1997, and then she did a live album almost immediately afterward. And it was like she was introducing this song to the audience.

And it’s like a breakup song. It’s like a diss song against the person who she’s just broken up with. And all the women in the audience are screaming the entire time, they’re so delighted and they relate to this song so thoroughly, so immediately.

Kim Deal’s voice is the ‘greatest musical instrument ever’

DG: I really love your take on the Breeders’ 1993 hit, ‘Cannonball.” Can you share your take on that?

RH: My take is that I love that song and the killer bassline, courtesy of bassist Josephine Wiggs. The Deal sisters’ audible switchblade smiles as they harmonize on the line, “Spitting in a wishing well.” The split second of dead air right after the Deals harmonize extra-sweetly on the line, “the bong in this reggae song.” The giddy insubordination of that silence, which packs more personality than any other band’s noise.

I’m from Ohio, right? I’m from the Cleveland area. I live in Columbus now. The Breeders are from Dayton. That makes a huge difference if you’re in Ohio and maybe not as big a difference if you’re not, but it’s Kim Deal’s voice, man.

Kim Deal’s voice is just the greatest musical instrument ever invented, in my opinion. There’s this quality that it has that’s so playful and so sinister at the same time, like a children’s librarian reading you the scariest story you’ve ever heard in your entire life.

And “Cannonball” was just such a blast of fresh air on the radio in 1993. You’re at the height of grunge. You’re at the height of the Pearl Jam, Nirvana, Alice in Chains at excess. And I worshiped those bands, and I worshiped them at great length in this book and on this show.

But “Cannonball” — the first 60 seconds is all sound effects. The song takes forever to get going in a way that’s so appealing to me. It just struck me as revolutionary at the time. I’m 15 or whatever, and I cannot believe that these people live in the same state that I live in. I can’t believe they live on the same planet as I do.

Episode Credits

- Doug Gordon Host

- Adam Friedrich Producer

- Steve Gotcher Producer

- Doug Gordon Producer

- Steve Gotcher Technical Director

- Jeff Daniels Guest

- Matt Singer Guest

- Rob Harvilla Guest

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.