When a student or teacher tests positive for COVID-19, the best practice, according to state and federal health officials, is to figure out who else they might have exposed.

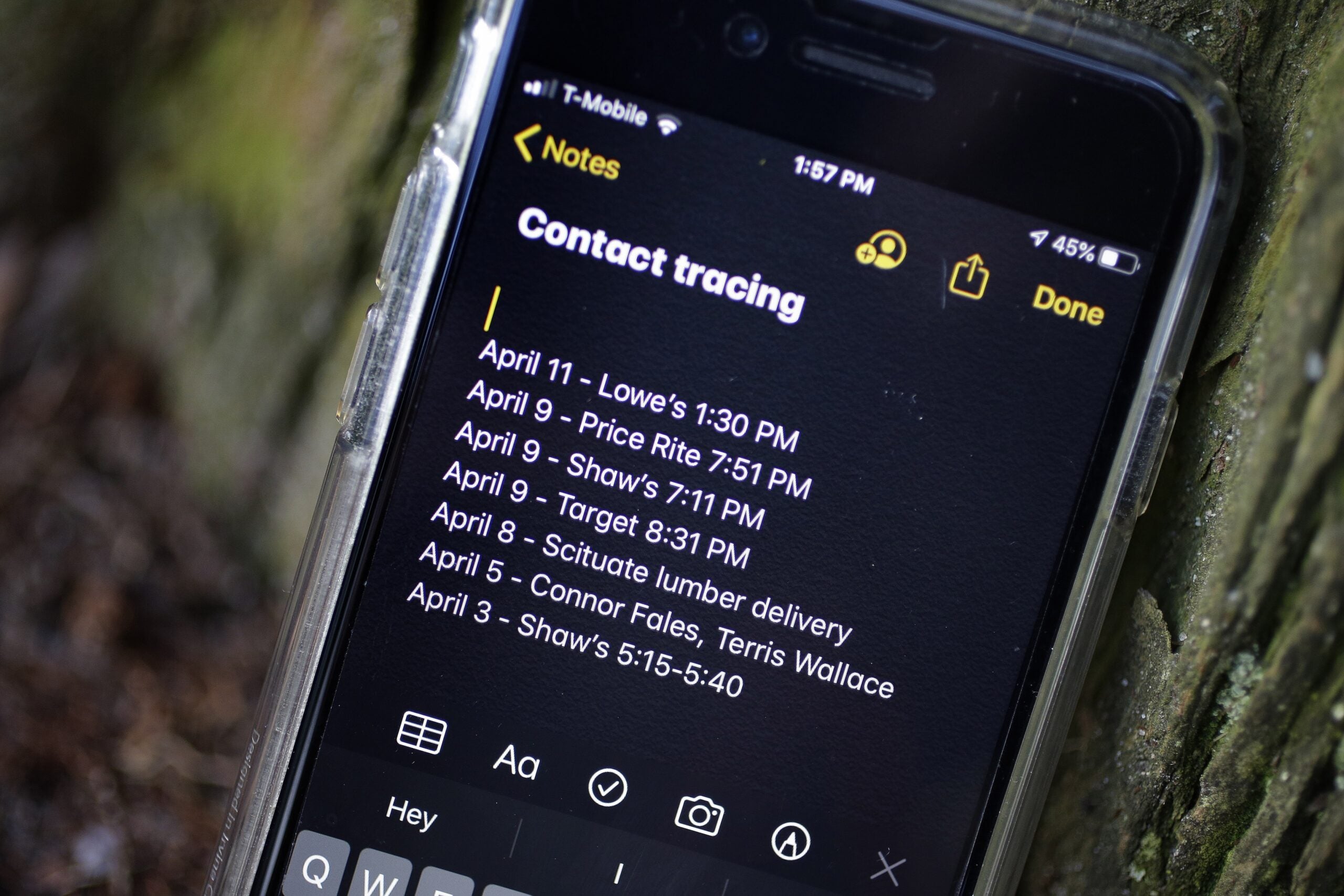

That’s done through contact tracing, one of the pillars of COVID-19 mitigation throughout the ongoing pandemic. It’s also been one of the most difficult to keep up with, almost since the beginning. As case counts grew, local health departments struggled to reach everyone who had tested positive.

Many Wisconsin schools set up their own contact tracing operation, with administrative staff and school nurses calling and sending notes home to families whose children had been potentially exposed.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As cases among young people have reached new highs this school year, though, schools have had to scale back.

“In the fall, we kinda trudged along. It was hard, but we managed, doing the best we could,” said Kaying Xiong, executive director of student services at the Eau Claire Area School District. “And then we came back in January, after winter break. The surge was just quite unbearable, with regards to just the simple capacity to make this happen.”

Xiong said the schools used to call each close contact personally to let them know they were exposed and to walk them through their next steps.

“We’re not really doing that anymore,” she said. “We’re relying on the child to take a note home from school, we’re relying on leaving a message, we’re relying on email to let the parents know that their child has been a close contact at school.”

The district has also shifted to focus on close contacts that were exposed in higher risk environments, like a cafeteria or during swim lessons, when they can’t wear masks.

On Jan. 12, the Madison Metropolitan School District sent parents an email saying it wouldn’t be sending emails, texts or phone calls to close contacts or providing school-wide notifications of positive cases.

“With positive COVID-19 case counts at unprecedented levels, our health services staff have needed to prioritize their work in order to stay ahead of an increased demand for services,” the email read. “As a result, health staff is shifting from tracing contacts of positive cases to contacting only individuals who test positive and their high-risk close contacts (household members).”

It’s not just schools that have had to scale back their contact tracing efforts. As Wisconsin health agencies have been swamped, first by the delta variant wave and now by a rush in cases driven by the omicron variant, organizations across the state have warned that they can’t notify everyone who was potentially exposed to someone who had tested positive.

But schools often struggled to meet contact tracing demands in the first place. For districts that have a nurse on staff, contact tracing was often added to their workload; many districts have only a part-time nurse, one nurse who covers several schools or no school nurse at all. Other districts have eschewed contact tracing altogether this year.

Doug Olson, district administrator for the roughly 500-student Kickapoo School District, said his district have kept up COVID-19 precautions like masking — over some parents’ strenuous objections — in part because he knew contact tracing would be a challenge.

“That was one of the reasons why we’ve held the line on universal masking, is because we do only have a half-time nurse,” he said. “The level of contact tracing and testing you have to do if you are mask-optional, I’m not sure we have the staffing to be able to support that.”

With children masked in school, Olson said the bulk of Kickapoo’s cases come from athletics or students and staff seeing family or friends.

Still, Olson said the district’s half-time nurse spends most of her time on COVID-related issues.

Xiong, in Eau Claire, said the work can be emotionally taxing, as well.

“I’m so exhausted,” she said. “It’s not just the work, it’s the feelings for our families, and for our staff who have to do this work.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.