With a voice that barely rises above the squirly excitement of her students, Andi Rubino corrals third, fourth and fifth graders into a circle on the floor in a large group space inside Lodi Elementary School.

The ages are mixed because these students attend Ouisconsing School of Collaboration (OSC) — a charter school within the Lodi School District that’s housed in the elementary school building about 20 miles north of Madison.

“The reason I have you in a circle today is because circles represent strength, they represent opportunities to have power and respect comes from everyone who’s a participant in this circle,” said Rubino, the school district’s psychologist and behavior specialist.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

She grabs an inflatable ball with questions written out for the students to answer: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “Hawaii or Alaska?” “What’s one cool thing we should know about you?”

The activity will help Rubino get acquainted with the students who she’ll see throughout the school year. In her first lesson, she keeps mental notes. She watches who’s eager to participate. She listens to their responses. She notices how well they communicate with each other.

School psychologist Andi Rubino and students at Ouisconsing School of Collaboration at Lodi school district listen as another student holds the ball and shares a fact about themselves during a lesson on social emotional learning. Liz Dohms/WPR

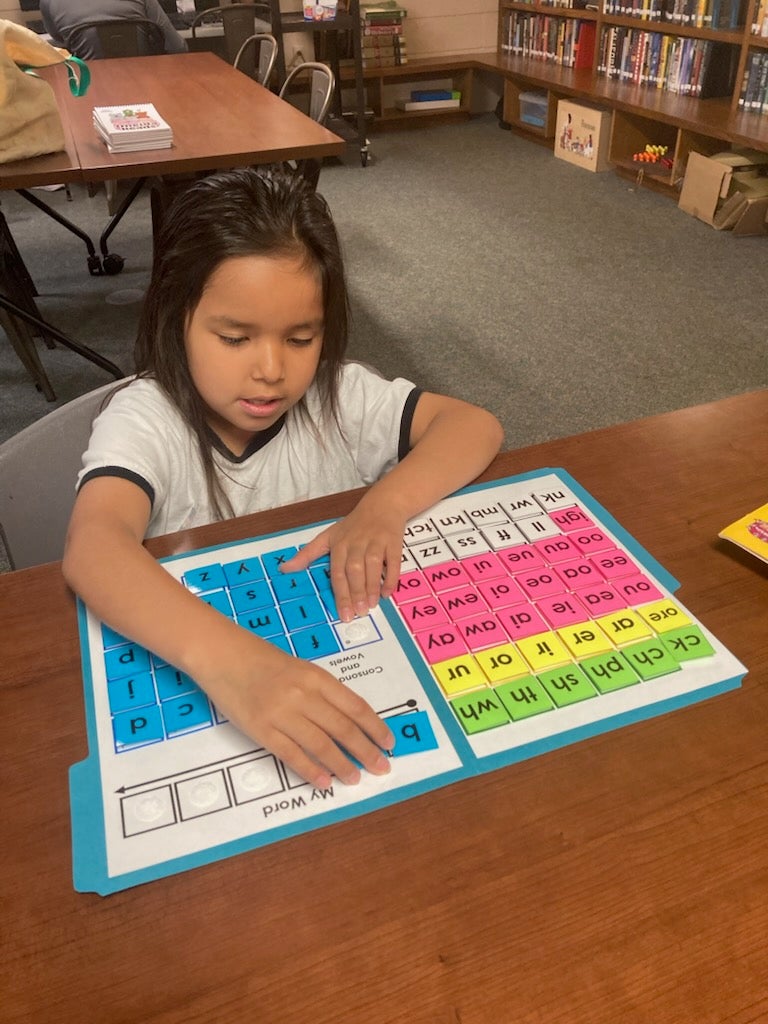

With the help of specific curriculum, Rubino will teach 317 students skills to better cope with stress, become more self-aware, learn self-control and show empathy in lessons all wrapped up into a type of programming called social emotional learning (SEL).

Similar to other schools, Lodi has adopted SEL practices that are now embedded in the classroom. But the school district is taking things a step further by measuring to see if these methods are working for its students.

This past spring was the first time students in Lodi took an assessment to gauge where they were when it comes to social and emotional well-being. The SSIS-SEL was used to assess students in kindergarten, third and sixth grades. Teachers completed the assessments for the younger students.

“The assessment that we’re using is more about how can we help them learn how to regulate their emotions,” said Tiffany Loken, who directs curriculum, instruction and student services. “Because we know that there’s a connection to that and their future mental health.”

On the whole, about 90 percent of students performed to standards on the SEL assessment, said Michael Pisani, principal of Lodi Elementary School and OSC charter school, which both serve students in grades 3-5.

That means that a majority of elementary-aged students had good awareness of self and others, they could manage and regulate their emotions and they made decisions in line with social norms and expectations.

The hope is that when these same students take the assessment again in higher grades, their responses will show that SEL programming is effective at helping to reduce anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation.

Students are assessed in five categories related to social emotional learning, according to the SSIS SEL. Graphic courtesy of SSIS SEL

What Current Data Show

In 2017, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey was administered to students across the state. Of the high school students in the Lodi School District who took the survey, about 18 percent felt so sad or hopeless every day for two weeks that they stopped doing usual activities. Twenty-one percent of middle school students responded the same way.

Eleven percent thought seriously about killing themselves, compared with nearly 12 percent at the middle school level.

The most recent version of the survey was given in February, but statewide data isn’t yet available.

Statewide data from 2017 shows that 16 percent of high school student respondents said they considered suicide, 15 percent made a plan and about 8 percent attempted it. Statewide data also found that 40 percent of high school students who took the survey in 2017 reported high anxiety. About 17 percent reported that they self-harm and 27 percent said they’re depressed.

SEL is a direct response to grave concerns over the wellbeing of students, and numerous schools have invested in programming aimed at social and emotional growth. Monona Grove School District near Madison starts students with these lessons in 4K and continue them through sixth grade. Students at New Glarus Elementary School start every Monday morning in the gym with breathing exercises and a monthly motto.

At Lodi, Rubino applies SEL curriculum in the classroom. That curriculum comes from Second Step, a program backed by the nonprofit Committee for Children that provides lessons, staff training, family materials, implementation resources, among other thigns.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction identifies Second Step as one of among 14 programs that are developed using research that supports the curriculum’s effectiveness.

Local school districts get to decide which curriculum to implement. At Lodi, that’s a task overseen by Loken.

“Social emotional learning has always been in the classroom to some degree,” she said. “I think it’s within the last three years that we are being more intentional about the idea and importance. It’s not just one more thing; it’s something we need to weave into everything we do.”

On a purely academic scale, SEL matters because students immersed in the program perform better on achievement tests in reading and math, according to DPI. Still, the ultimate goal of SEL is to produce an emotionally and mentally stable child, teenager and ultimately adult.

“The way that we look at reading and math, now we’re looking at social emotional learning through that same lens,” said Pisani, the Lodi principal. “What’s the instruction? What do we want kids to know? How do we know when they know it? What do we do when they do and what do we do when they don’t?”

Across all boundaries

Lodi is considered a rural community. Almost all students are white and the poverty rate hovers around 20 percent as measured by free and reduced lunch participation. That’s low compared to other school districts. Some students come from farming backgrounds but a vast majority of parents commute to Madison for work.

Without racism and poverty being contributing factors, mental health issues have still seeped into the district, substantiating claims that few, if any, districts can insulate their students from these health crises, Pisani said.

Data from students across the state show mental health challenges across the board.

Loken said it could be adverse childhood experiences, trauma or chronic stress that can lead to high levels of anxiety and depression. Rubino agrees, and says that maybe these issues are more prevalent because people are paying attention to them.

But one thing is clear: There are too many barriers outside of the school network to provide assistance for students who need help, whether that’s in the form of transportation, high deductibles or copays or a shortage of providers.

“There’s a much greater need than there are providers, so we are, at some levels, it,” Pisani said.

The fact that the burden of addressing mental health falls to school districts might at some levels seem unfair, but school districts don’t really have a choice when it comes to attacking these problems head-on, Pisani said.

“(Not responding is) morally and ethically against what every educator signs up to do,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.