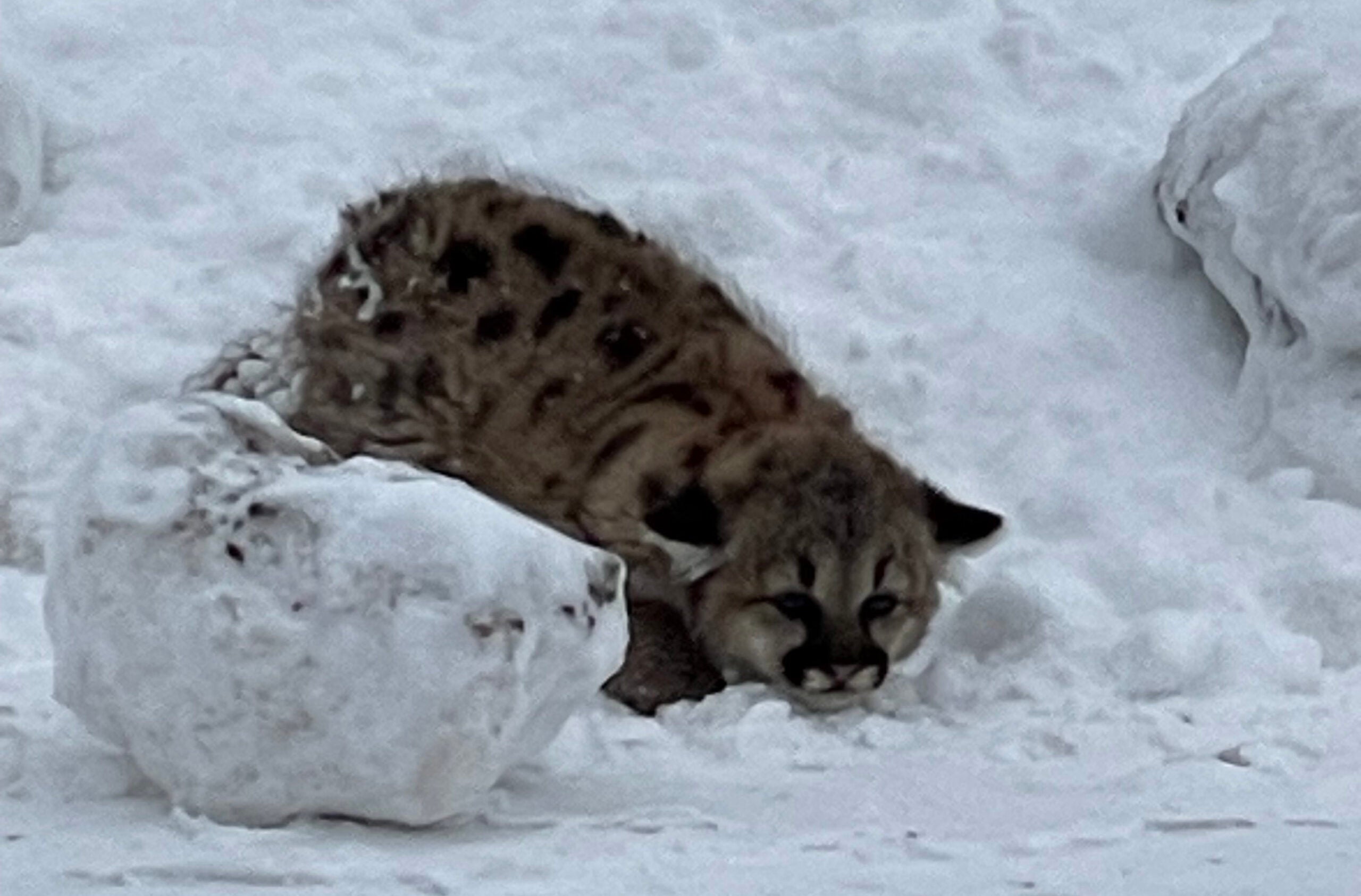

Three newborn bear cubs left the intensive care unit at a Rhinelander wildlife rehabilitation clinic last week and are continuing to healthily grow in the facility’s care, the clinic’s co-founder said recently.

Mark Naniot, the director of wildlife rehabilitation at Wild Instincts, said the three cubs have doubled in size since the facility has been treating them after the cubs’ mother died from an “unfortunate accident” during research in February. Naniot, speaking on WPR’s “The Morning Show” last week, said researchers suspect the cubs’ mother suffocated after they tranquilized her and an older cub, and the cub rolled over onto his mother’s head.

He explained that cubs in their second year don’t usually go into the den with their mothers so “it was a little bit of an unusual situation” to also have to tranquilize the roughly 125-pound cub. He said the researchers were in the den to replace the batteries on a radio collar they used for research, although Naniot wasn’t sure what specifically they were studying.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Naniot praised the researchers for immediately calling his clinic, getting the three new cubs into their care within about two and a half hours.

Over 25 years, he said this was only the third time something has happened during a research project that ended with bringing cubs into the facility’s care.

“This was an accident, and sometimes things happen,” he said. “There’s a lot of good information that we found over these research projects. We try to participate whenever we can.”

It’s true that sometimes it is best to let nature takes its course, but it isn’t always just nature that creates a need for Wild Instincts.

“What we feel is: Humans broke it, so we should fix it,” he said.

And fixing it, they are. Naniot said the three cubs are eating well, albeit still from a bottle.

“They’re just starting to be able to stand and take a couple of wobbly steps at this point,” he said.

Fixing it, however, isn’t cheap. Bear cubs are among the most expensive animal they raise, Naniot said. The care for each cub this young is about $3,000 or $4,000 per cub during the eight months they are usually at the clinic.

As a nonprofit, he said Wild Instincts doesn’t get funding from federal, state or county governments.

It might be common to assume bears mostly eat meat, but that isn’t true. They eat a lot of berries and vegetation, so Wild Instincts buys a lot of grapes, bananas, apples, peaches, pears, plums and other produce. The produce truck that comes about once a week is pretty costly, he said.

Last year, he said the clinic handled more than 1,300 animals of all stripes. Wild Instincts relies on donations, something they’re always seeking. And with the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of fundraisers have been canceled.

It’s hard to find workers, too. Normally, Naniot said they have a lot of interns applying for positions across the spring, summer and fall. But this year, he said no one applied for their spring internship.

Unfortunately, he said that means he and his staff will have to work 16- or 17-hour days, seven days a week, to give care to all the animals coming in.

“You never know what you’re going to do from one day to the next,” he said. “We’re cleaning toilets one minute and feeding bears the next minute. So, it’s a situation where we have to basically do it all.”

There are a little more than 100 wildlife rehabilitators in Wisconsin, he said. At his own Rhinelander clinic last year, they took in animals from 43 different counties.

Dealing with a large geographical range can be challenging. He said the average career length for a wildlife rehabber is about three years — thanks in part to compassion fatigue, long hours, low pay and giving up vacations.

“I’m a fulltime volunteer,” he said. “I’ve only had one day off in the last 10 years, and that’s only because I was too sick to function.”

But Naniot is still at it, still fixing. He said he can count on one hand — and maybe have a finger or two left over — how many people he knows who have been doing this work as long as he has.

He said they recently bought 53 acres of land to their north in hopes of creating an educational nature center.

Wild Instincts needs a lot of space to operate. That’s part of why it isn’t a very attractive industry to join, he said.

For example, the three bear cubs are still spending their time inside. Naniot said they will need to make about three or four more moves before they can be in the final large outdoor enclosure.

The cubs should be strong enough to go off on their own by about mid-October.

“They’ll be at that point anywhere between 100 and 120 pounds and perfectly capable and ready to go back out into the wild and do their thing,” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2026, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.