For more than 50 years, medical professionals around the world have used the same system for diagnosing patients with traumatic brain injuries. A Milwaukee researcher is among a group of global medical professionals calling for a new way to diagnose and inform treatment for injured brains.

Medical professionals have traditionally used the Glasgow Coma Scale since it was introduced in 1974 to assess patients for traumatic brain injuries. It evaluates a person on several factors, including how a person’s pupils react to light and how they respond to questions. The scale labels patients as either having mild, moderate or severe head trauma.

But Michael McCrea, director of the Brain Injury Research Program at the Medical College of Wisconsin, told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that categorizing patients into just three categories is overly broad.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“There’s no disease state in modern medicine, where the classification is limited to mild, moderate, severe,” McCrea said.

“Patients who had experienced traumatic brain injury — and the families of those patients — are just incredibly dissatisfied with the way we’ve been doing things,” he added.

McCrea, also a professor of neurosurgery and neurology, is one of the authors of a new classification system released in May that wants to build beyond the Glasgow Coma Scale.

How would this new system work?

The authors of the new way of diagnosing traumatic brain injuries is calling this the CBI-M framework.

The new system would update how medical professionals detect brain trauma to have them screen for how suspected head trauma patients’ eyes react to light. Having one or both of a person’s pupils dilated could indicate moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, according to Mayo Clinic.

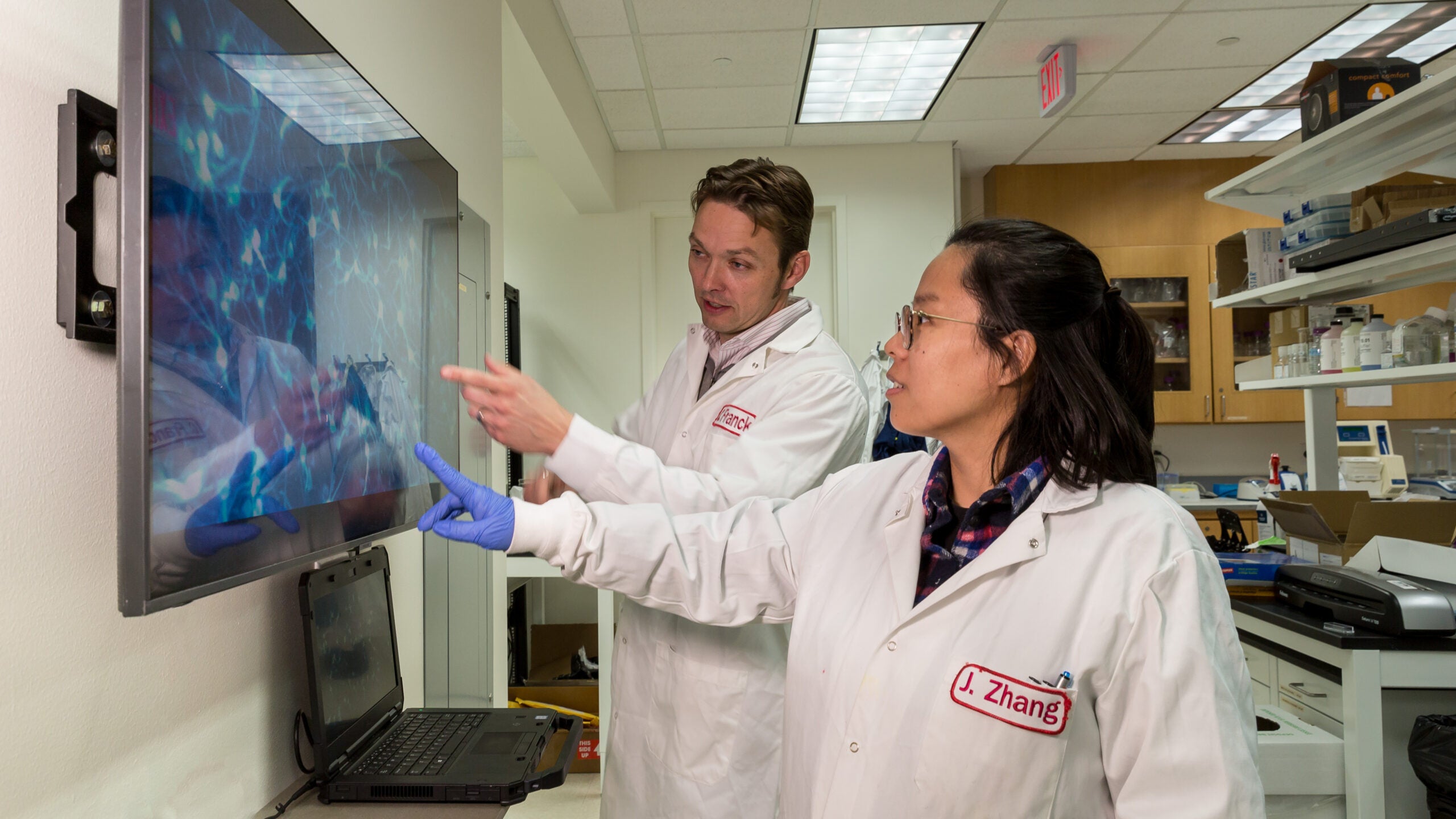

But the newly proposed framework would also use a patient’s blood samples, plus an improved method of analyzing CT scans, to improve diagnoses. McCrea said recent scientific advancements over roughly the last decade allow medical staff to detect possible brain bleeds from blood drawn from a patient’s arm.

“Elevated [blood] biomarker levels can indicate the likelihood of a brain bleed on imaging, and we can fast track that patient to a [CT scan],” McCrea said. “On the other side, very low levels of these biomarkers might prevent somewhere in the order of about 30 percent of unnecessary head CT [scans] after minor head trauma.”

The new system would also examine a person’s social system and their social environment.

“Whether someone may have a prior history of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, whether they be homeless or gainfully employed, do they have an intact social support system at home? Do they have insurance coverage?” McCrea said. “All of these are important factors for me to take into account when creating a care plan, particularly a follow-up care plan, for patients affected by traumatic brain injury.”

Researcher says new system has utility outside of the hospital

McCea said he and a colleague are exploring how this system to diagnose traumatic brain injuries could be used outside the hospital. He said this new method could be very valuable in a variety of settings, from the sidelines of a football field to an active war zone or the scene of a car accident.

“In a motor vehicle crash that’s 45 minutes from the major level one trauma center but five minutes from a local community hospital, that [blood] biomarker test in the field conducted by paramedics or EMTs could immediately … [help] determine whether they should be taken directly to the level one trauma center or if it’s adequate to take them to the local community hospital,” McCrea said.

McCrea said he and his colleagues are working with scientists who are developing ways to implement this framework into emergency departments around the world.

“It might seem … as long as something is going to improve care for patients and improve chances of survival, recovery and return to maximum life after injury, that doctors start doing it,” McCrea said. “But it requires a pretty massive educational effort to make emergency department physicians and other providers aware of this new framework and to create a workflow for them to plug into their everyday practice.”