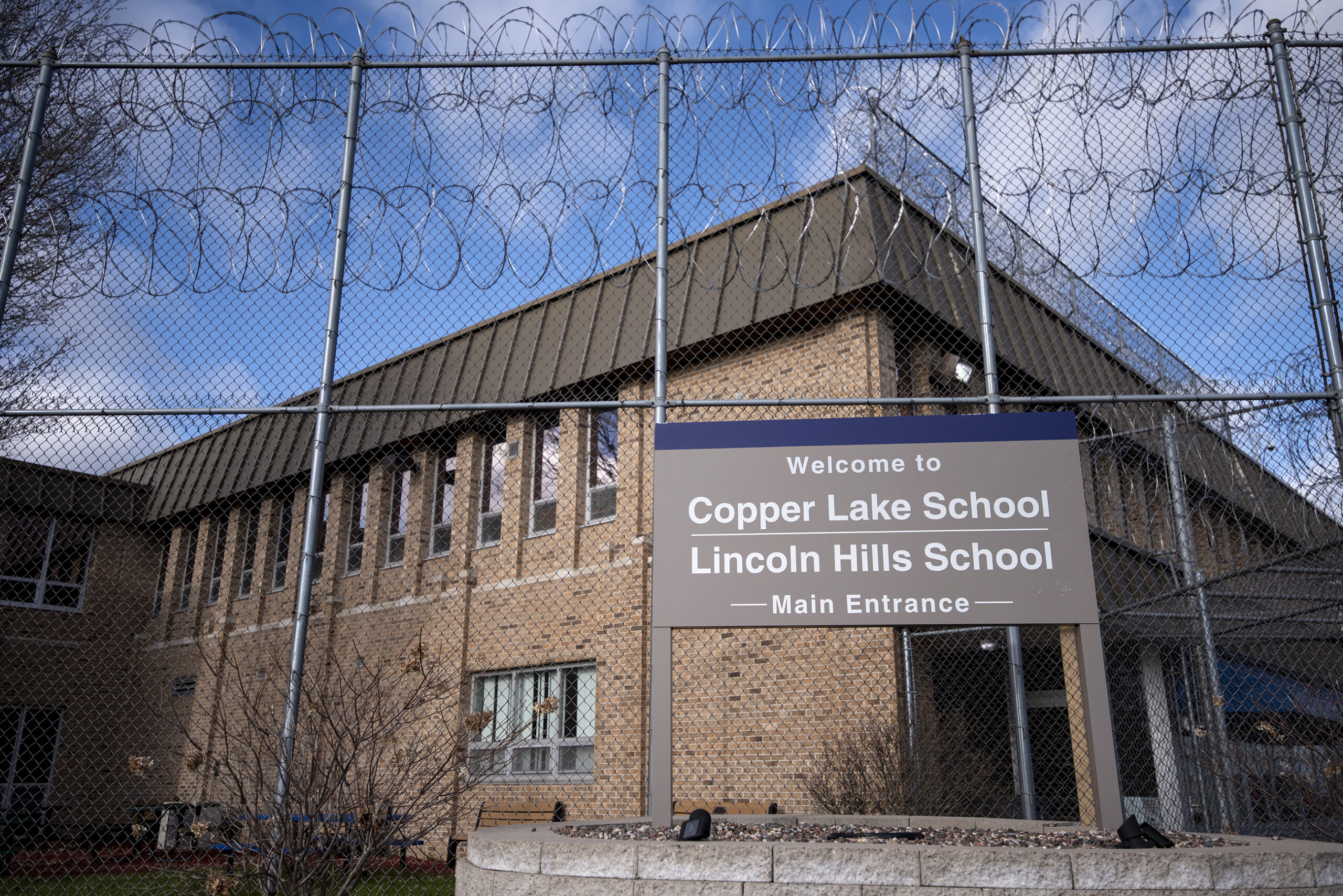

A new therapy technique at Wisconsin’s Lincoln Hills youth prison holds the promise of making the facility safer for both staff and youth. But implementing it requires buy-in from an overworked, sometimes cynical prison staff — and advocates for youth justice reform say it’s not a substitute for the state’s promise to close the facility for good.

Dialectical behavior therapy, or DBT, emphasizes communication and relationship-building between prison staff and youth inmates. State leaders say it means a culture change at the facility, and since late 2020, staff at all levels of the Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth facilities have undergone training and begun to incorporate the techniques into their work with youth. These include daily meetings between young people and staff including social workers, teachers, guards and administrators.

Research on DBT has found it can be effective in reducing violence in correctional institutions, and a court-ordered monitor praised the facility’s transition to the therapy, writing in January that she was “encouraged by the progress and commitment made in implementing DBT.” In a new report released Tuesday, the monitor wrote that there had been “vast improvements” at the site, and said that “DBT implementation will be very beneficial to youth and staff.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But state leaders acknowledge that implementing the new techniques will be a big change for the troubled institution, including among security staff who are not used to its emphasis on positive reinforcement and seeking to understand the root causes of behavior rather than simply control it.

“We are in the very, very, very early stages of this,” said Lesley Chapin, a psychologist who is leading training at the facility. She’s working with staff members and sitting in on some of the sessions.

Chapin said she’s seeing progress at Lincoln Hills School. She also said she’s aware that some staff members are taking a jaundiced view of the changes.

“The nature of these facilities is they’ve seen a lot of stuff come and go,” she said. Some staff “probably expect that this is the flavor-of-the-day.”

Danna Villafane, now 18, spent two years at Copper Lake School, first for stealing a car and then for an armed robbery charge. She got out last year, before the DBT program started. But she saw plenty of efforts at making change there.

“They’ve tried this so many times,” she said. “They have so many programs there they got trained for, and none of it worked. They just don’t listen. (The guards) decide what they want to do and, in their eyes, we do what we want to do.”

Reforms Need To Counter Years Of Dysfunction At Lincoln Hills

During Villafane’s time at Copper Lake, one of the therapy techniques was “thinking fingers,” meant as a way for youth to calm themselves by massaging their temples while they were getting upset. It wasn’t exactly embraced. She said guards taunted her as they locked her up in solitary confinement: “Use your thinking fingers, Villafane.”

“They weren’t saying it in a good way,” she said. “They were making fun of the situation, taking it as a joke.”

Villafane earned her high school equivalency degree at Copper Lake, and said she had good relationships with some staff members. But overall, she said, it’s not a good place.

“It impacted me in a negative way,” Villafane said. “It didn’t impact me in a way where I wanted to change my life around. … I was angry in there.“

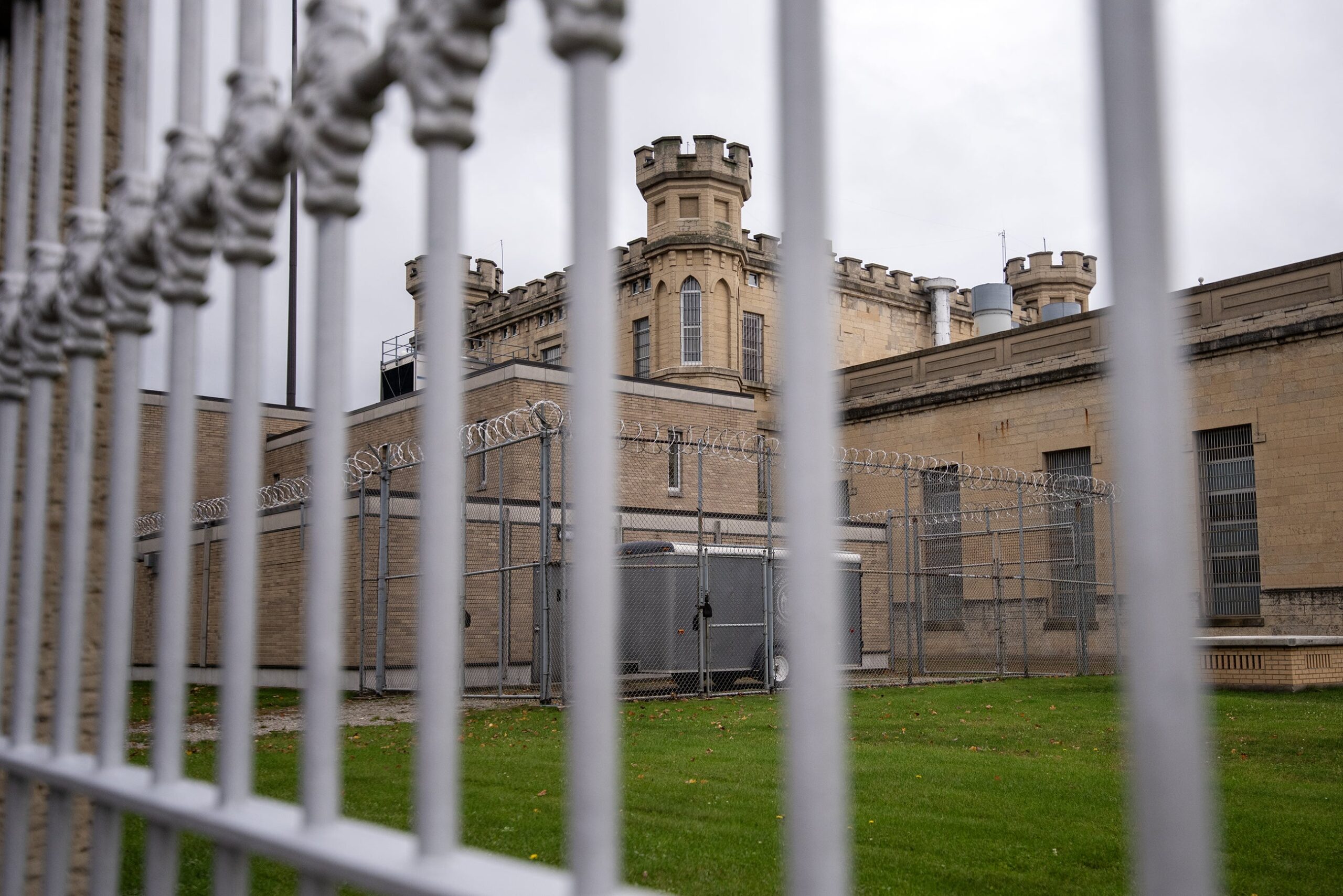

The problems at Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake are deep-seated, and its history includes abuse by staff members, violence by youth against teachers, mismanagement and an overuse of disciplinary measures such as solitary confinement. For years, memos from judges, public defenders and psychologist groups pointed to evidence of mistreatment by staff, poor training and insufficient medical care for inmates. Some staff members retired or resigned after probes of misconduct; some were fired. An FBI probe closed without charges.

In 2018, a federal judge responded to a class action lawsuit brought by the American Civil Liberties Union by ordering changes to the facility, including regular reports by an independent monitor. Beginning in early 2019, those reports have chronicled both progress and resistance to changes that include eliminating the use of pepper spray and punitive solitary confinement.

Staff at the facility say their jobs are unsafe; as recently as February, a staff member was taken to a hospital after an assault by a youth inmate. In January, the monitor found a majority of staff were “stressed and frustrated.”

The facility is chronically understaffed, meaning workers there face sometimes-mandatory overtime that can extend their 12-hour shifts to 16 hours.

The Wisconsin director of AFSCME, the union that represents workers at Lincoln Hills, declined repeated interview requests. WPR interviewed a current employee at the facility, who said some of the court-ordered changes have made the facility less safe and less orderly. WPR is not revealing the employee’s name because the person was not authorized to speak publicly.

State officials point to positive statements in the most recent monitor’s reports to show that implementation of DBT techniques are already improving conditions. And they hope the reforms can make a lasting difference.

“I have a lot of faith in our staff and a lot of respect for their abilities to be adaptable and learn new skills,” said Wisconsin Department of Corrections Secretary Kevin Carr. “I believe that if given the chance and if our folks really are dedicated to serving the youth in the best way possible, they’ll be able to make this transition. It’s just going to take some time.”

Carr met with staff at Lincoln Hills in March to discuss safety issues and learn about DBT implementation. He said it’s “a marathon, not a sprint,” and success will be measured over time in whether incidents of violence “go down significantly.”

“That’s when I will say, ‘Hey, this is doing what it’s supposed to,’” Carr said.

Governor, Activists Push To Rethink ‘Unfixable’ Youth Prison Model

One thing that’s made hiring and retaining staff at Lincoln Hills difficult is the fact that there are real questions about whether or not the institution has a future. The state’s first deadline for its closure was Jan. 1, 2021. When Gov. Tony Evers and other leaders said the state wouldn’t meet that deadline, the Legislature extended the deadline to July of this year.

But even as the new deadline looms, no concrete plans exist to close the facility.

For advocates of youth criminal justice reform, the implementation of DBT or other changes at the facility simply don’t go far enough.

“I’m glad that now the staff are talking to the kids,” said Sharlen Moore, executive director of Milwaukee’s Urban Underground. “What the hell were they doing before? It just goes to show you that the practice of how these young people are supported was not healthy.”

The 2018 bill, signed by then-Gov. Scott Walker as he was gearing up for a reelection campaign that year, would have moved Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth to smaller, regional facilities, and turned the Lincoln County institution into a minimum-security state prison for adults. The next year, Republican legislators left a gap of more than $100 million in funding for alternative facilities, including in Milwaukee, the state’s largest city where most youth inmates come from. And the process of setting up regional facilities had setbacks, as some counties have found creating them too expensive.

Moore said it’s worth looking even deeper at what Wisconsin actually needs.

The population of incarcerated youth in Wisconsin has dropped dramatically. In 2002, the average daily population of the state’s three youth facilities — Lincoln Hills, Copper Lake and Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center — was 819. By 2019, the three institutions housed 156 kids on average. Today, the combined population of Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake hovers between 60 and 70 kids. That’s many fewer than what the capacity of four to six regional facilities would be. Mendota, a secure mental health treatment facility in Madison, received $59 million in the state’s 2019-21 biennial budget to expand its capacity from 29 boys to 60 boys and 40 girls.

“We have to put more resources on the preventative side,” said Moore, whose organization supports underprivileged youth. “It’s not just, when a young person gets in trouble, we say, ‘You know what? We’ve got a really nice jail for you.’ … We’ve got to start looking at it very differently.”

Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake have “school” in their names, but those who work or visit them say there is no mistaking them for what they are: prisons. A southeastern Wisconsin mom whose daughter was at Copper Lake described her first visit to the institution. They sat across from each other at a cafeteria table.

“My daughter was upset,” the mother said. “She was crying, and she reached out to me to hug me.”

Guards immediately separated them. The fear is that an embrace would allow visitors to pass contraband items — drugs, weapons, electronics — to the youth.

“As soon as you do more than touch your child’s hand, you have to be separated,” the woman said.

WPR is not identifying the woman in order not to identify her daughter, a minor at the time.

For Chapin and Carr, implementing DBT can improve outcomes for youth at Lincoln Hills even as a broader political debate continues in the state over the future of youth corrections.

“I’m not the one who is going to make that decision” to close Lincoln Hills or not, Chapin said. “But I know it’s not closed. And if it’s not closed, I want to do everything I can to make it a treatment-focused facility.”

At an event in Milwaukee this month, Evers promoted a range of juvenile justice reforms in his proposed state budget, including an end to charging juveniles in adult court — and, again, the closure of Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake.

“We’re also going to propose to close Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake so that we can get our kids closer to home as soon as we safely and responsibly can,” Evers said. “Wisconsin is ready to make this change.”

If the Legislature turns out not to be ready to make that change, youth criminal justice expert Vincent Schiraldi said the state should reassess its system from top to bottom. Schiraldi, a former New York City probation commissioner who is co-director of the Columbia Youth Justice Lab, said it’s hard to make any reform stick at a place like Lincoln Hills.

“These large, prison-like institutions entropy in this direction,” Schiraldi said. “That’s why we need to close them. … In the meantime, it’s probably good to have good therapy programs going on in such facilities, but we should not mistake that for the notion that somehow Wisconsin is going to come up with a way to fix the unfixable.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2024, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.