Two researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison are part of a new effort to improve understanding of how and why glaciers move the way they do — and to explore efforts to save glaciers and prevent drastic sea level rise.

In March, Luke Zoet and Marianne Haseloff with the university’s Department of Geoscience became the first recipients of grants from the Arête Glacier Initiative.

The initiative is a collaboration with Dartmouth College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was founded in 2024 to improve understanding of how fast ice sheets in Antarctica melt and to explore ways to potentially stabilize glaciers.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Zoet told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” that cities on the East Coast like Miami have very shallow shorelines, leaving them particularly vulnerable to the effects of sea level rise.

“If you just raise the baseline water level, the effects of those tides will be felt farther inland, and they’ll get more of these nuisance flooding events, where places experience flooding during high tides,” Zoet said.

“By increasing sea level, you’re increasing the base level and everything else has to adjust to it,” he added.

UW researchers: Loss of ‘doomsday glacier’ could raise sea levels significantly

The conversation on glacier loss involves one body in West Antarctica: the Thwaites Glacier.

Journalists have dubbed this body of ice as the “doomsday glacier” because of the potential domino effect if the glacier were to break apart and fall into the ocean.

Zoet has been to the Thwaites Glacier several times and described it as a “plug in the bathtub” for other glaciers in that region of the South Pole. He said the collapse of this glacier could result in upwards of 6 feet of sea level rise at minimum if it breaks apart.

“You could potentially get quite a bit of sea level rise in a short period of time, and that is at the heart of the problem. How quickly is the sea level rise going to go up? [That] means that’s how quickly humans have to adapt to it,” Zoet said.

Haseloff said the concern over the western Antarctic ice sheet isn’t over the glaciers melting; it’s about them quickly breaking apart and sliding into the ocean.

Haseloff compared the danger of the quick dislodging of ice sheets into the ocean to adding ice cubes to a glass of water.

“The ice sheet can move very quickly, and this can go much faster than melting alone,” she said.

New research aims to improve understanding of how glaciers move

Both researchers have received grants from the Arête Glacier Initiative to better scientists’ understanding of glaciers and ice sheets.

Haseloff said her research focuses on mathematical equations that aim to more accurately predict how ice sheets and glaciers move — and how that relates to the small area of bedrock the glacier rests upon.

“There’s a chance that you have at some point stepped on ice that was just a little bit wet, maybe in early spring … the same goes for ice sheets,” Haseloff said. “When they sit on a bed where it’s just a thin film of water, for instance, then that can help the ice sheet slide along. And understanding that is really important in understanding West Antarctica.”

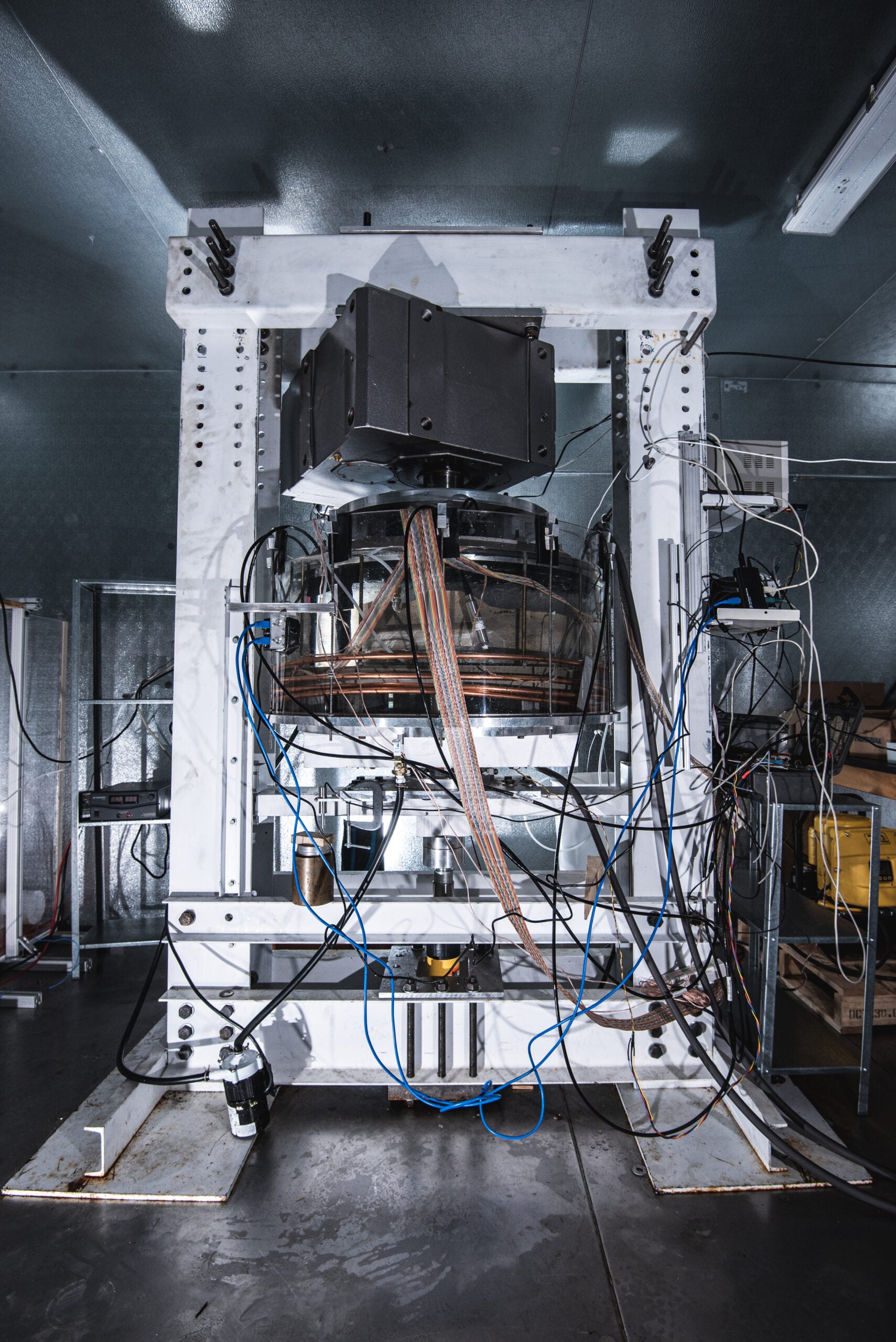

For his research, Zoet is working to build the second machine in the world to create a simulated glacier. The machine, called a cryogenic ring shear device, creates a large donut of ice that the machine can spin in fixed conditions to test how a simulated glacier could move over bedrock in different conditions.

“In nature, it’s really hard to [test] because there’s so many things going on simultaneously that it can be difficult to untangle one part from the other. But in the lab, we can systematically change one variable at a time and see how it responds,” Zoet said. “It takes all the complexity of the real world and puts it in a system where we can control it.”

Zoet said his research could potentially help scientists essentially refreeze a glacier to its bed through a method called basal intervention. This would involve humans drilling holes through a glacier and using a well to remove water from the base of a glacier, reducing water pressure from below a glacier and more tightly pairing a glacier with its bed.

“That’s where the ring shear experiments in the lab comes into play,” Zoet said. “We drill a hole through the ice, and we can suck the water out from the bed, all the while we can see what’s happening to the bed as we’re doing that. We can see what’s happening to how fast the glacier is moving. We can include a lot of these complexities that you might have in the real world … as sort of a midpoint between the field and theory.”