There’s an unsettled new mystery dividing the art world. A painting of a fisherman purchased at a Minnesota garage sale in 2016 is now thought to be a lost artwork by acclaimed Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh — worth $15 million, according to a new report.

And a Wisconsin expert was brought in to do some literary detective work.

Susan Brantly is a professor in the German, Nordic and Slavic department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A few years ago, she got a call from art research firm LMI Group asking her to lend her expertise in reading and analyzing 19th-century Scandinavian literature to help authenticate an artwork.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I didn’t know initially what the call was about — that there was some painter or another,” Brantly told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “And then came the reveal [that it was Van Gogh], and I just was grinning from ear to ear. I couldn’t have been happier. I thought, ‘Oh, this is too cool for words.’”

New York City-based LMI Group uses data science alongside traditional artistic and historical analysis to verify the artists behind possible lost masterpieces.

“We apply the deepest and widest analysis to determine whether what we call an ‘orphaned’ artwork is indeed a work by the attributed artists,” said Lawrence Shindell, founder and CEO of LMI Group, who studied at UW-Madison and spent 20 years of his career living in Wisconsin.

“There’s a lot that needs to go into authenticating a work that has been lost to history and is finding its way back to the world, and it needs to be done in a conclusive, fact-based way,” he said.

Shindell told “Wisconsin Today” the firm’s art authentication process is a bit like detective work, identifying clues and following leads, and then presenting something like a “legal case” with their evidence.

“That’s the inherent nature of having to go back and, as others kind of analogize what we do, uncover and solve that ‘cold case’ — in this case from almost 150 years ago,” he said.

Solving an art history mystery

This painting of a fisherman came to the firm’s attention in 2019 after the buyer, an antiques picker in Minnesota, contacted the group on a hunch the painting’s impasto — a technique of applying a thick coat of paint — was reminiscent of Van Gogh.

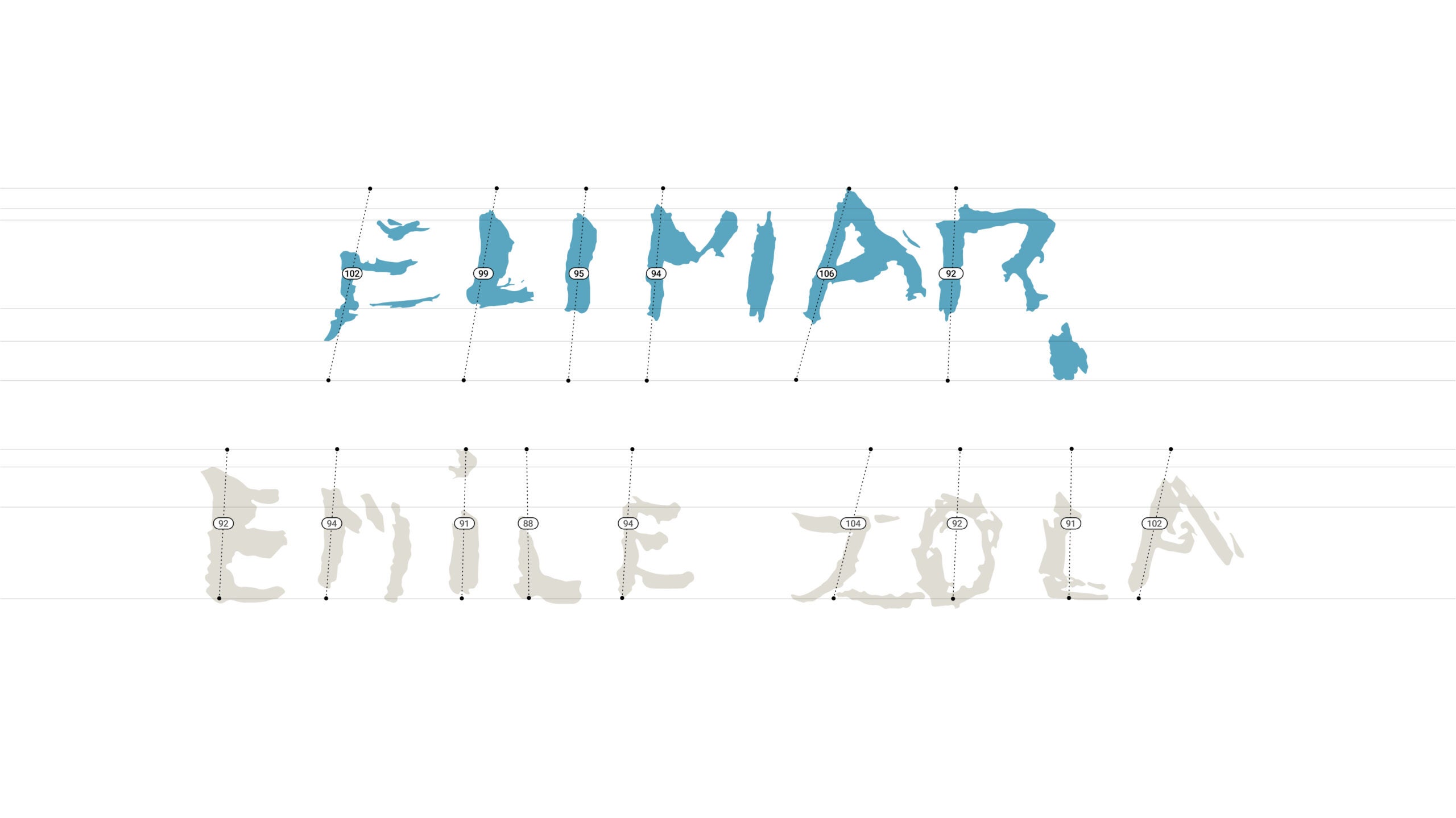

After seeing the painting in person, Shindell and his colleagues determined it was worthy of an investigation into its origins. Their experts got to work looking at the subject matter and stylistic features of the painting, analyzing the paint colors and brush strokes, and doing a mathematical computational analysis of letters in the inscription on the lower right: “Elimar.”

Then, of course, there was the question: What does “Elimar” mean and why might Van Gogh have included this inscription? That’s where historical and cultural analysis comes into the process.

“The broader historical context with a work like this is where, in a bespoke way, we would assemble the right kinds of experts to zero in on that part of it,” Shindell said. “So we went about looking for the top experts in Scandinavian literature from the 19th century, and lo and behold, Susan [Brantly] was at the top of the list.”

Brantly, who has been teaching at UW-Madison since 1987, describes herself as a “frustrated art historian.” For years, she has used visual art to illustrate her classroom lectures about literature, and she sees the two as intertwined. But never before has she been involved in such a high-stakes mystery from the art world, and she was excited to dive in.

“The first time you look at it, you could say: ‘What? That’s not a Van Gogh. Everybody knows what a Van Gogh looks like,’” Brantly said.

But while researching the painting and its possible literary origins, she became convinced they had a real Van Gogh on their hands.

The theory is that this image of a fisherman was originally created by Danish painter Michael Ancher. Van Gogh would have seen the painting and done what he called a “translation” during his year at a mental hospital in the south of France in 1889. That’s known as a prolific period when he created 150 paintings, many of them copies of other works.

Brantly was able to uncover the possibility of Van Gogh seeing the Ancher painting through an analysis of handwritten letters (in Danish) between artists Christian Mourier-Petersen, who met Van Gogh in 1889 while living in the south of France, and Johan Rohde, who later became known for introducing Van Gogh’s art to Denmark.

As for “Elimar,” Brantly believes this is a reference to a character from “The Two Baronesses,” an 1848 novel by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen, best known for writing children’s fairy tales.

Describing Van Gogh as a “voracious reader,” Brantly thinks he may have encountered this story as a young man, “maybe even a child,” and that it resonated with him because it featured a character prone to “violent fits” similar to what Van Gogh himself experienced throughout his life.

“I’m a storyteller. Stories are my area of expertise,” Brantly said. “It’s when I start getting into the stories … that it just makes so much sense to start connecting the dots.”

Van Gogh … or no?

After years of research, LMI Group released its findings in a 458-page report that includes a chapter from Brantly on the literary connections, along with additional historical context, assessment of the painting’s composition by art connoisseurs and even DNA analysis of a red hair that was embedded in the paint.

The firm believes they have a real masterpiece that has been lost to history.

But the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, widely considered the authoritative source on the matter, has rejected the attribution, saying “Elimar” is not a Van Gogh in their estimation. The Wall Street Journal reports the museum has recently fielded as many as 500 authentication requests per year.

Brantly said she wasn’t expecting this outcome given the breadth and depth of evidence offered in the report.

“I’m a little disappointed, but actually mostly surprised. This is the first time I’ve ever been in these sort of exalted fine art circles, and am learning astonishing things,” she said. “Reputations are at stake, not to mention a great deal of money.”

Shindell was also disappointed with the outcome and feels the evidence has not been weighed carefully.

“Bear in mind that the museum … hasn’t seen the painting,” he said. “No one has really given any explanation or detailed reason against the attribution. No one has identified any foundational fact in the report that they say is inaccurate.”

Shindell said this is not the end of the road for “Elimar” and his team’s efforts to get it recognized. He hopes the facts they found will speak for themselves.

“This painting is, in many ways, the most intimate reflection of Vincent van Gogh and his inner self,” Shindell said. “Why would anyone not want that to be front and center in everything that we know about the artist?”

As for Brantly, she is staying on the case, too.

“I’m not done with this,” she said of the painting. “I think about it all the time. There are more things that I would like to find out, more questions I would like to answer about it, so I’m still working on it.”

Brantly is giving a presentation about her work on the Van Gogh mystery on May 3 at 19 Ingraham Hall on the UW-Madison campus. The event is free and open to the public.