A new report published by University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers in the journal Current Biology may hold clues to an unfolding mushroom mystery: the origins and possible consequences of the invasive golden oyster mushroom.

According to the study, golden oyster mushrooms have been spreading rapidly throughout the Midwest since they were first discovered growing wild in the 2010s. They also reduce the diversity of fungi living on the dead trees and wood they grow on by about half.

That could disrupt the processes that other species in Wisconsin forests rely on.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Tree seedlings, small animals, insects, birds — all of these things depend on dead wood habitats,” lead author Aishwarya Veerabahu told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “(Golden oyster mushrooms are) seemingly chewing through them rapidly and bringing them down. What does that mean for the rate of wood decay, the rate of carbon emissions from that wood decay and the dead wood habitat that results from it?”

An invasive mushroom mystery

Golden oyster mushrooms have risen in popularity — for eating — in recent decades. The bright yellow fungus might be found at the local farmer’s market or sprouting from grow kits that allow people to plant them at home. They have a nutty flavor and are easy to grow.

But the origin of the encroaching fungi, now prevalent in the southern part of Wisconsin, is unclear.

Wisconsin Mycological Society President Mariah Rogers told WPR she first encountered wild golden oyster mushrooms in 2017. At that time, rumors swirled within Wisconsin’s foraging community about how the species had infiltrated the state.

Some speculated that it was related to the spread of the emerald ash borer, since people were finding it on dead ash trees. Others heard they came from a fire at a mushroom farm in Iowa — or was it Indiana?

What we do know is that in the 2000s, golden oyster mushrooms were brought to North America from their native range of eastern Russia, northern China, and Japan. But it wasn’t until 2014 that they were first observed growing wild in Wisconsin.

Citizen scientists in Wisconsin help track the spread of golden oyster mushrooms

In 2018, UW-La Crosse biology master’s student Andrea Reisdorf wrote her thesis on where golden oyster mushrooms in the U.S. may have come from — the first academic attempt to answer the question. Reisdorf’s research suggests that golden oyster mushrooms growing in the U.S. likely came from a small number of commercial mushroom strains that escaped, not in one specific instance, but multiple times.

“In terms of cultivated mushrooms that we eat, it seems to be the first one we’ve seen that has escaped cultivation and spread so rapidly,” said Veerabahu, who’s a doctoral student in the UW-Madison Department of Botany.

More recently, scientists at UW-Madison’s Pringle Laboratory noticed a steady increase in reports of golden oyster sightings from citizen scientists on biodiversity databases like iNaturalist and Mushroom Observer. That’s what prompted Veerabahu and her colleagues to conduct the recent study.

“That entire body of amazing, curious people out there saw the mushrooms and started talking about them and noticing, ‘Hey, we haven’t seen this here before. What are they doing here now?’” Veerabahu said. “It was really word of mouth that spread (the news) about them.”

What to do if you find golden oyster mushrooms in the wild

Jason Raiti, forager and member of the Madison Mycological Society, told WPR that he sees masses of golden oyster mushrooms every time he goes out foraging or trail-running in the forest.

“If you find native oysters, you might find a small clump growing on a log,” Raiti said. “But with golden oysters, wherever I’ve found them, there’s usually a million of them — they’ve completely taken over whatever they’re growing on.”

Unfortunately, Veerabahu said, we can’t eat our way out of the problem.

“Its mycelium is throughout the wood and possibly in the soil, so there is no extracting it from the environment once it’s in a place,” Veerabahu said.

The exception, she said, is if someone thinks they might be observing the first instance of golden oyster mushrooms in an area. In that case, they might be able to prevent it from taking hold.

“I would try and contact a local official who has authority over removing that wood, or if it was on (my) property, I would try to remove that wood and burn it,” Veerabahu said. “There’s no guarantee that that would get it out of the place, but it’s at least an attempt.”

Veerabahu said that another way people can help track and contain golden oyster mushrooms is by reporting their observations online.

“They absolutely can help monitor the spread,” Veerabahu said. “This project would not exist without community scientists posting their observations on online biodiversity databases.”

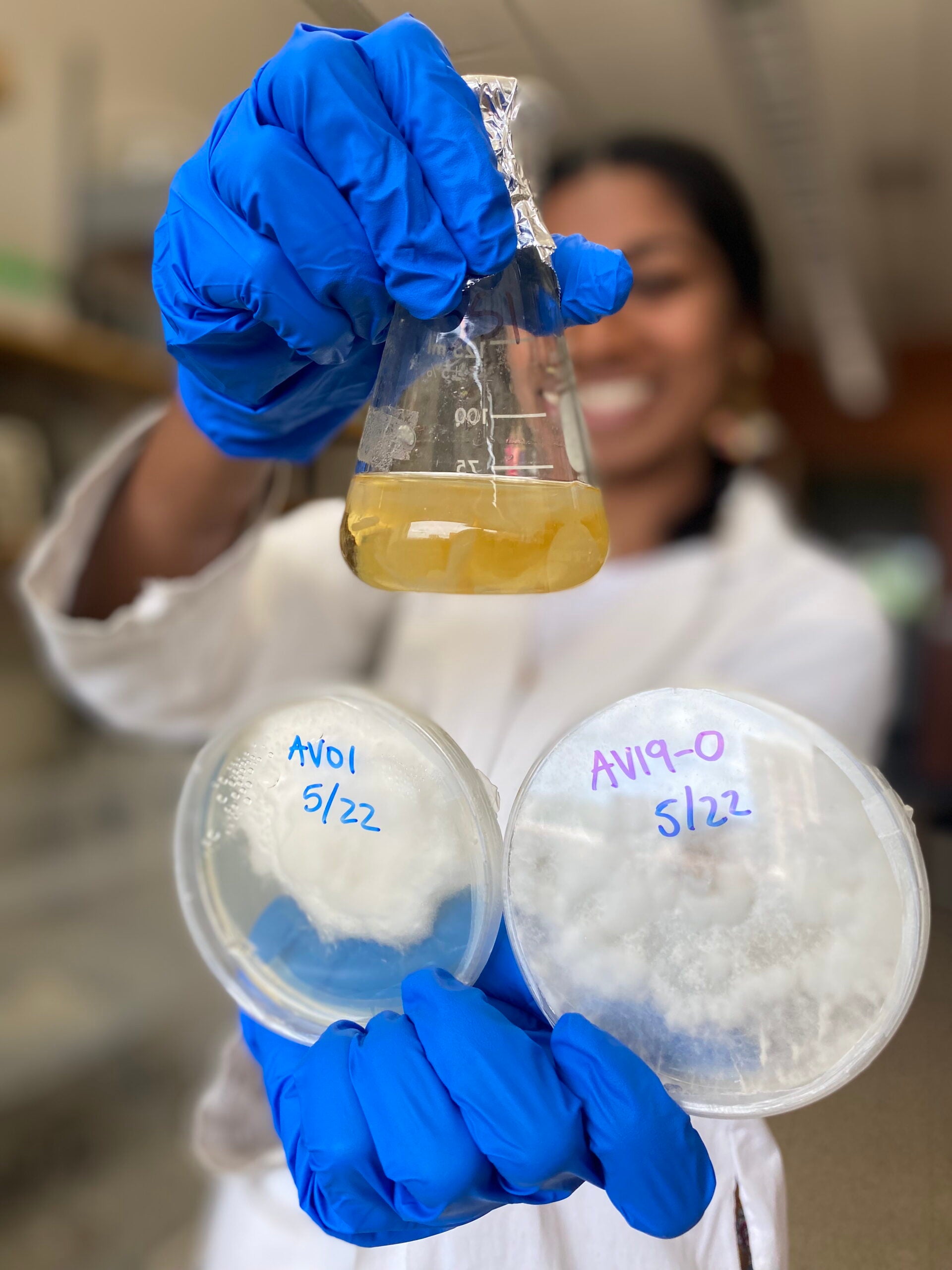

Veerabahu is also asking citizen scientists all over the U.S. to send her samples of the mushrooms, which she plans to genetically compare with golden oyster mushrooms in their native range in Asia to explore why they’ve been so successful here in the U.S.

Rogers, from the Wisconsin Mycological Society, suggested that when it comes to non-native fungi, foragers should avoid their usual practices of intentionally spreading wild mushrooms.

She also expressed the importance of keeping golden oyster mushrooms out of the northern part of the state, where they haven’t yet taken over.

“The biggest thing I try to impress on people is that if you’re trying to still (forage them), to not be transporting them too far from where you’re collecting them,” Rogers said.