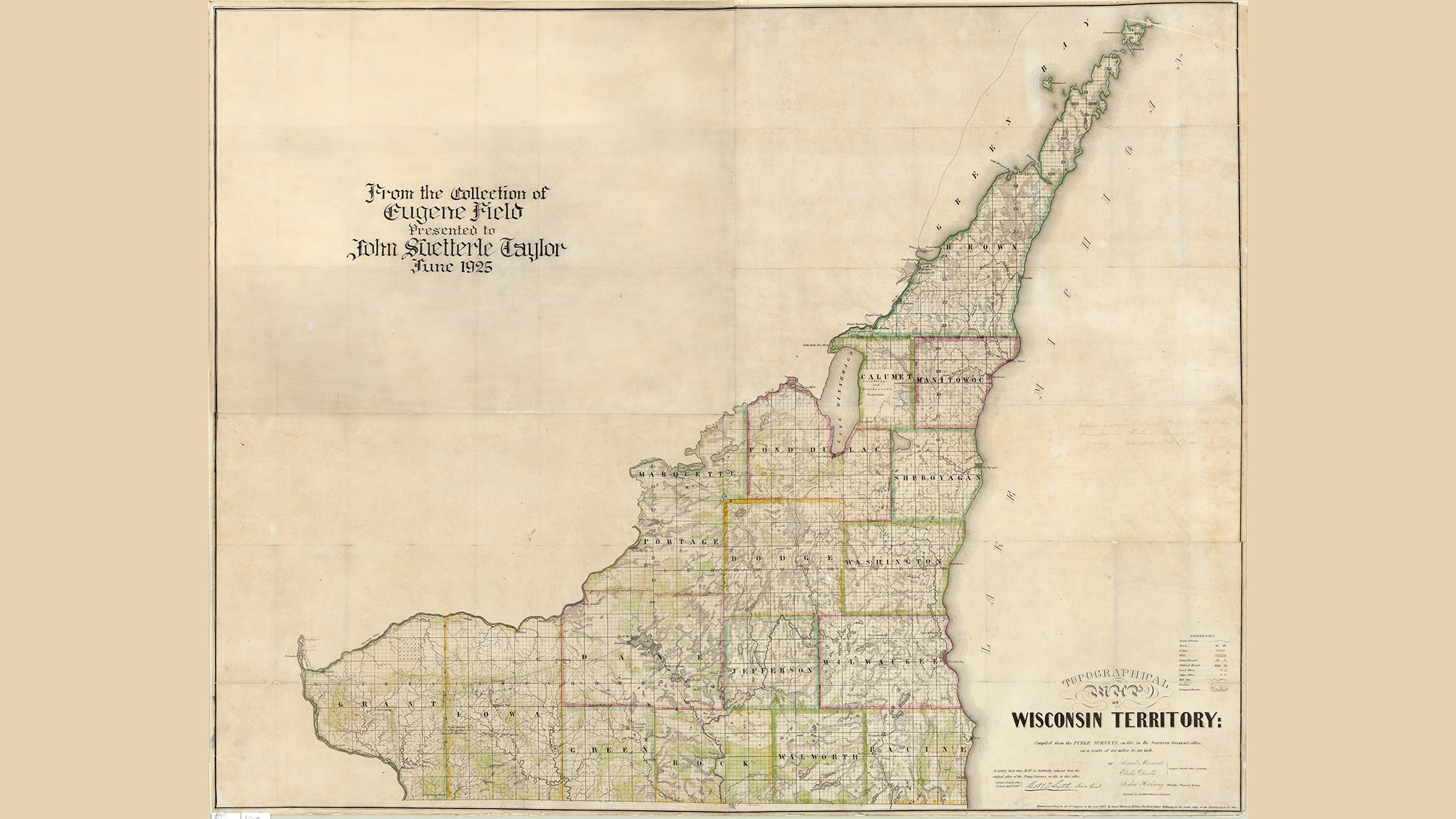

Wisconsin lies more than 500 miles from the western end of the Erie Canal in Buffalo, New York. Yet it was the completion of that marvel of engineering 200 years ago that put Wisconsin on the map for so many early settlers.

In 1835, a decade after the canal was finished, there were only a few thousand non-native people living in Wisconsin. “By 1850, there were 305,000,” author Laurie Lawlor said recently on “The Larry Meiller Show.”

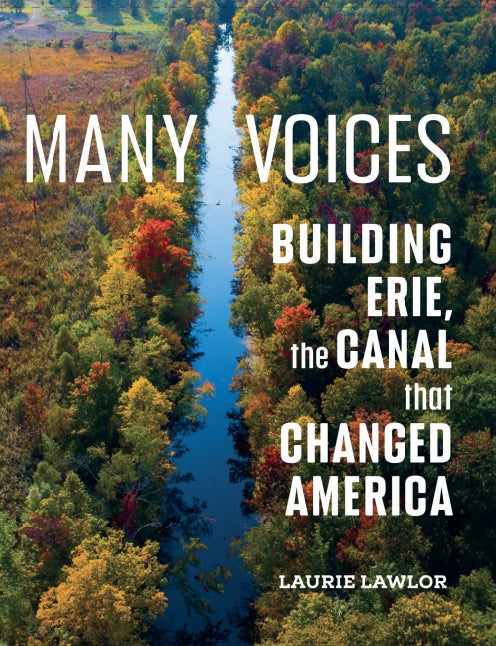

The Erie Canal caused a “population surge” in Chicago, Milwaukee and other Midwest cities, according to Lawlor, author of the new book “Many Voices: Building Erie, the Canal that Changed America.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Published in September — on the 200th anniversary of the completion of the Erie Canal — the book details how the 363-mile Erie Canal connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes, bringing an unprecedented number of people and products westward.

The Erie Canal originally cost New York State $7 million, the largest public works project of its time, helping alleviate rapid immigration and overpopulation of cities along the Eastern seaboard. The canal also dispossessed many Indigenous people along its wide path.

Yet the canal provided easier passage through a still wild landscape, before railroads and largely impassable by mere wagon roads.

Lawlor told Meiller about John Griffin, who made the arduous trip to the Wisconsin Territory in 1842. His story was one of several Lawlor uncovered but couldn’t include in the book because of space constraints. In a subsequent article for WPR, Lawlor shared her research.

“I felt haunted by these individuals’ letters and journals. Like so much about the complex and compelling Erie Canal, Wisconsin immigrant experiences embraced everything from creativity and cowardice, sacrifice and greed, heroism and prejudice,” Lawlor wrote.

Griffin and his family traveled to Milwaukee “by foot, wagon, train, and boat.”

In family letters held by the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives, Griffin wrote of being “terrified” during the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. According to Lawlor, Griffin’s belongings were shipped on an Erie Canal line boat before he and his family sailed across the Great Lakes on a steamer.

With relief, the 1,300-mile journey over 16 days ended in the Milwaukee area. “I like the look of the country and shall live and die here,” he wrote.

Then 44 and a widower, Griffin bought 112 acres of tallgrass prairie in Waukesha County, which he farmed. He later lost much of his eyesight to the ague, or “swamp fever,” and died of a stroke in 1855. He was buried on his farm near Eagle.

Four years before Griffin arrived in pre-statehood Wisconsin, terrible fortune befell Ole Knudsen Trovatten and his family as they made a similar trek.

After a rough crossing on the Atlantic, the Norwegians arrived in New York City and were towed by a steamer up the Hudson River to Albany. That’s where Ole “was robbed of all his money while sitting on the dock,” Lawlor recounts. “He had no money to buy food, so he spent a great deal of the (journey up the Erie Canal) begging for bread from other passengers.”

In Buffalo, he offered his rifle as collateral for a loan to buy boat fare through lakes Erie, Huron and Michigan. But upon arrival in Milwaukee, Ole again had to beg to feed his family — made more difficult by being unable to speak English.

“I felt that things had become too heavy for me to bear. I regretted very much that I had left Norway,” he journaled, according to Lawlor.

The Trovattens eventually made it to Muskego, where they farmed. Ole’s wife and children died of cholera. He reportedly died of alcoholism, in poverty, in 1860, Lawlor wrote.

Lawlor will talk further about the impact of the Erie Canal on agriculture in Wisconsin and the Midwest at a book signing at 4.p.m. Sunday, Sept. 28, at the Boswell Book Company in Milwaukee.